The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists have returned to the 1607 burial ground and are preparing to disinter three individuals who died in the first few months of the settlement. Buried just inside the eastern wall of James Fort — per the Virginia Company of London’s instructions not to reveal their losses to the Virginia Indians — over 30 individuals are located here. Since the graves in the 1607 Burial Ground are not marked with the identity of the individual interred, the challenge of matching the human remains with the Virginia Company list of names of those who died that year falls to archaeology, forensic science, and genomics. Fort Pocahontas — the Confederate earthworks built in 1861 on the same high ground where the first settlers built James Fort — protected these burials from the harmful wet/dry cycles nearer the surface with several additional feet of soil. After the removal of Fort Pocahontas’ earthworks in this area, the individuals’ remains are now much more susceptible to these cycles, so there is a sense of urgency to save the remains from simply dissolving into the soil. It was evident during the 2022 burial excavations that changing the topography of the site above the graves is having an adverse effect on the human remains. Proceeding after consulting the Jamestowne Society, an organization of the descendants of Jamestown settlers, and employing rigorous ethical standards as a guide for their excavations, the archaeologists are using science to determine as much as they can about those who are exhumed. The archaeology team is interested in discovering where they came from, diet, cause of death, relatedness to other previously-exhumed individuals, and possibly even their identities by comparing their DNA to that of living relatives. Eventually, all individuals excavated and studied at Jamestown, including these three, will be respectfully reinterred.

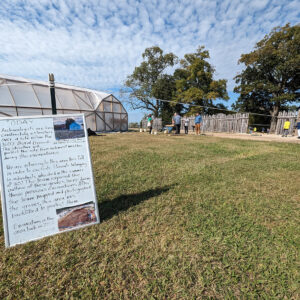

The outlines of the graves in the 1607 Burial Ground were discovered during excavations from 2003-2008, but a vast majority of them were left unexcavated. Most of the graves were photographed and recorded with surveying equipment, and then covered back with soil to protect the site. One person who was excavated in 2005 is thought to be Richard Mutton, a boy killed in the first Virginia Indian attack on the settlement on May 26, 1607. A quartzite projectile point was found next to the boy’s left femur. Prior to this fall’s excavation, the archaeologists conducted a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey over the backfilled area to confirm the location of the three burials they planned to excavate. Once the location was confirmed, the backfill soil was mechanically removed back down to the level the graves and other features were initially encountered. Above the site, archaeologists constructed a burial shelter, not unlike a greenhouse, wood-framed and covered in translucent plastic. The shelter will protect the human remains from the elements and also from DNA contamination by present-day organisms.

The graves found in this area of the site in 2008 were not the only features left unexcavated. Excavation in 2008 stopped at the ca. 1607 ground surface, and revealed a myriad of postholes, ditches, and other features. Once reexposed, the team was able to probe this ground surface further, and uncovered several more postholes. Among these finds was a wall for a mud-and-stud building, as well as a mid-17th-century palisade. Both the building and the palisade cut into one or more of the burials, as do a few other features. The remains of the palisade’s individual logs can be seen in the form of dark, organic staining, left behind when the logs decomposed in the ground. Archaeologists term these “post molds,” since they are earthen casts of what the logs originally looked like.

The mud-and-stud building was heretofore unknown, and four postholes for the structure have been identified so far. Mud-and-stud buildings at Jamestown universally date to the first few years of the English colony. This means that only a year or two after people were actively buried in this space, the colonists needed to intrude upon it to erect a structure. The team is certain the building dates to after the burials since one of the postholes cuts into an interment. This is a basic archaeological principle: a feature that cuts another is newer than the one which was cut into.

Part of the work in this area involved digging into the ca. 1607 ground surface, both to identify and clarify the new features, and to prepare for the burial excavations. Artifacts found in this soil and the surrounding features predominantly date to the early 17th century or before. Large sherds of Virginia Indian ceramics — many of the Townsend variety, which predate the English colony — have been recovered, as have indigenous projectile points and a partial pipe stem. Some of these artifacts are thousands of years old. English colonial artifacts of note include lead shot, a partial Robert Cotton pipe, three Nueva Cadiz beads, and several aglets.

Most interestingly, the archaeologists also uncovered two rim sherds for a small porcelain vessel in the overburden layers at the burial site. When Curator Leah Stricker saw an image of the porcelain fragments, she quickly recognized them as likely belonging to a partially mended tea bowl housed with Rediscovery’s reference collection. Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid joined Stricker and Senior Curator Merry Outlaw in the Vault with the porcelain to determine if the newly discovered sherds would mend with the bowl. They did! Other fragments of this vessel have been found in the fill of James Fort’s second well (ca. 1611) and in a plowzone layer near that well at the north end of James Fort.

Excavation stopped in the area once the ground surface was only a few inches above the human remains in the burials. Throughout the excavation process, Director of Archaeology David Givens uses high-frequency GPR to determine where and how deep the remains are. Once the team is within a few inches, GPR is used to create a three-dimensional image of the remains, so they know exactly where the individual is inside the grave shaft. The use of GPR has allowed the archaeologists to be extremely precise and careful when exposing the remains, living up to the “dirt surgeon” moniker Dave often uses to describe our team. The care the team takes is both out of respect for the individuals who were buried here, but also to help ensure we can learn as much as possible about these people and their lives. Peter Leach, an expert in GPR from Geophysical Survey Systems, Inc. (GSSI) and longtime collaborator with the Jamestown Rediscovery team, was on site to assist with the remote sensing surveys. Once the remains are exposed, forensic anthropologist Dr. Ashley McKeown will examine them in situ. By reviewing the disposition, preservation, and attributes of the individuals within the grave shafts, we can learn a lot about their lives and sometimes the circumstances of their deaths or their standing in the colony. After this examination, the remains will be carefully removed and brought into our lab for further study, and so they can be protected from deterioration

Assistant Curator Emma Derry is preparing the lab to receive the remains so that they can be processed properly. All of the necessary supplies have been gathered, including the Tyvek suits that she and the rest of the staff will be wearing while working with the remains. Other members of the curatorial and conservation staff are processing the artifacts just found in the Governor’s Well. Archaeological Conservator Don Warmke has made great strides in the conservation one of the swords found in the well. This sword is a rarity in the Jamestown collection, having a connected partial blade, hilt, handle, and pommel. Much of the corrosion has been removed and, as the X-ray suggested, it bears a resemblance to a Spanish-made sword in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Senior Archaeological Conservator Dan Gamble is working on another sword, this one having a partial blade, hilt, and tang. Dan’s carefully removing the corrosion using an air abrader, a pen-sized tool that spits out a fine stream of aluminum oxide particles at high speed. He has likewise made good progress and iron is now visible where once corrosion totally encased the sword. Some parts of the hilt are bent or broken. Dan is also conserving the spoon found in the Governor’s Well. Working through a microscope and using a scalpel to painstakingly remove the corrosion layers, the shiny tin surface is beginning to come through.

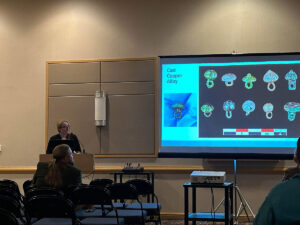

The volunteer team is making headway on sorting through some of the smaller artifacts from the Governor’s Well. They are separating the objects by size, removing the larger artifacts and leaving the tiny finds for picking through later by the curatorial staff. Animal bones and teeth are among the finds, the identification of which will give us insight into the colonists’ diets while the well was in use. Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens is comparing architectural materials from the Governor’s Addition excavations to those found in the Governor’s Well. The two structures were just a few feet apart and are thought to have been built at about the same time. One of the object types that she is comparing are bricks, the manufacturing of which can leave telltale signs on them indicating that they were made using the same production methods. The composition of the clay itself may indicate it was sourced from the same pit. These are the types of clues Lauren is looking for in her comparison. Assistant Curator Janene Johnston attended the Southeastern Archaeological Conference in Chattanooga where she presented on the 17th century buttons in the collection. Next year the conference will be held in Williamsburg, so we’re looking forward to having our colleagues come visit!

A number of the wood fragments found in the Governor’s Well have been slow dried, but most that are large or are intentionally shaped (such as the first wood comb found at Jamestown) are going to undergo PEG (polyethylene glycol) treatment and freeze-drying. The PEG treatment bulks the wood and is done on-site but the freeze-drying process will be done by a third-party. These processes prevent deterioration of the wood due to moisture loss, the common symptoms of which are shrinking, warping, and cracking. Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins is investigating methods of preserving the rope found in the well. It is being kept in water to preserve it until the proper conservation methods are determined. Assistant Curator Emma Derry has been able to identify the bulk of the animal bone found in the well. Many cattle bones have been identified, possibly all from the same animal. Several of the teeth found in the well belong to pigs. Bones from deer, rabbits, and other small rodents have also been identified. The presence of head and foot bones from the cattle and pigs indicate that the animals were butchered on site rather than shipped from overseas as meat. This suggests the colonists were involved in livestock farming during the life of the well. Some initial research has been conducted on the shoe fragments from the well. Most of the shoe pieces are soles, but a latchet — the strap piece that comes up over the arch of the foot near the ankle — was also found. One of the shoes is a child’s, about a UK child’s size 11. An outside researcher familiar with our collection has concluded that some of the fragments do belong to the same shoes. And a “patch” on one of the larger shoes is actually an intentionally placed piece called a “dutchman.” This piece helps the wearer with overpronation, and indicates that the shoe was custom made. This shoe is about a UK adult size 5 and could have been worn by either a man or woman.

Several jet or jet-like objects have been found at Jamestown, notably small crucifixes bearing similarly styled depictions of Jesus on the cross. It was long assumed that the jet for these objects was from the Asturias region of Spain. But Whitby, England has also been a center of jet mining and working for centuries. Crucifixes similar to the ones found at Jamestown have been found in Whitby. To settle the question of the origin of these artifacts, samples from seven jet objects and one jet-like object were sent to Dr. Richard Hark at Yale University for isotopic analysis. These results can then be compared to that of jet mined from Whitby to see if they were sourced from the same area. The one “jet-like” object has characteristics of both jet and of wood and so will undergo carbon dating to ascertain its age. True jet is much older than wood and the carbon dating test should settle the matter definitively. In order to obtain the samples for Dr. Hark, Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins used a Dremel with a sub-1mm diameter diamond-tipped drill bit to collect 2 milligrams of material from inconspicuous areas on the jet artifacts. This process is a component of the research of Sarah Steele, a postgraduate researcher and gemologist specializing in Whitby jet.

Third party researchers awarded a Skiffes Creek grant to study native textiles in the Cheseapeake region were in the lab this month to create a 3D scan of one of the clay pots in the Jamestown collection. The pot is thought to have been made by one of the colonists, perhaps Robert Cotton, Jamestown’s earliest pipe maker. Its exterior bears the impression of a Virginia Indian basket as the pot was formed by pressing clay against the basket’s interior. As such, the basket’s pattern is imprinted on the outside of the pot. The basket was made of plant fibers, finely woven and twisted and it likely carried one of the many loads of corn the colonists acquired from the Indians which they depended on to sustain themselves. During the pot’s firing process, the basket was burned away, leaving just its impression. It is this imprint that the researchers are interested in, being rare surviving evidence of a Virginia Indian basket from this period. The researchers are creating a 3D scan of the pot for further study. You can learn more about this rare artifact on its webpage or by reading “Incorporating the Other: A Seventeenth-Century Virginia Indian Basket Rendered in Clay” by Beverly A. Straube, former Senior Curator for Jamestown Rediscovery. The basket pot is back on display in the Archaearium museum. A 3D print of the basket pot will be on display in the Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia Community House and Interpretive Center.

Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown is combining the archaeological record with his photography and 3D modeling skills to present James Fort and its environs both in their historic contexts and in the present day as a way to bring awareness to the challenges sea level rise is presenting the archaeological team. Gabriel is using the Unity 3D engine and georectified photographs of excavations through the years to create a sort of virtual Jamestown, with the archaeological features exactly where they are on the landscape within a fraction of an inch. Further geographical data is provided by drone-produced LIDAR scans of the fort area, providing a highly-accurate survey of land and water features. The Unity 3D engine is typically used to make games but its near photo-realism, geospatial accuracy, and its ability to portray change over time has made it an able tool to show changes on the Jamestown landscape. Excavations at the late-17th-century clay borrow pit have been difficult and at times impossible because of the growth of the Pitch and Tar Swamp. Archaeologists in the 1940s were able to conduct excavations on dry land in the middle of what is now a swamp, the result of 1.5 feet of sea level rise since 1927. The Unity engine allows Gabriel to display those numbers in a visual way on the landscape, bringing the data home in a way that numbers by themselves cannot. Although very effective in this capacity, the potential for other uses is limitless. There is the possibility to present the landscape as it was at different points in time, informed by the archaeological excavations and the historical record.

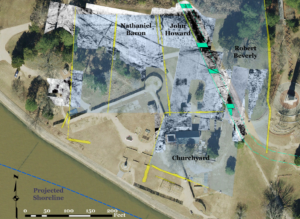

A cross discipline effort by the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeology team and historians is helping reconstruct the 17th-century landscape of Jamestown Island. The team is merging historic documents, 17th-century maps, and archaeology to identify 17th-century buildings, property lines, roads, and other features. This project follows in the footsteps of work done by Martha McCartney in the early 2000s; since then, the Rediscovery team has identified thousands of archaeological features, offering new opportunities to connect people and places to their exact locations at Jamestown.

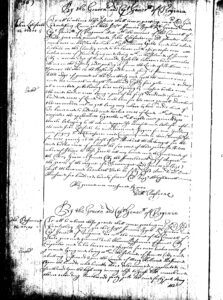

The first step in this work was to transcribe the surviving 17th-century land patents for Jamestown. This daunting task has been the purview of Dr. Amy Stallings, Public Historian with Jamestown Rediscovery and Adjunct Professor at William & Mary. Amy has deciphered the handwriting on dozens of patents, the bulk of which are housed at the Library of Virginia, with a few also at William & Mary’s Swem Library. Though the patents’ cursive is generally pleasing to the eye, it can be very hard to read, and the style and language of the text can be difficult to comprehend as a modern reader. Amy’s work necessitated a keen eye for detail and an understanding of 17th-century culture.

|

|

The patents often describe boundaries using 17th-century survey terminology, which is where Willie Balderson, Jamestown Rediscovery’s Director of Living History and Historic Trades, stepped in. Willie is well-versed in the terms and methods of 17th-century surveying, and was instrumental in translating historic distance and angle measurements to their modern equivalents. Willie also identified 17th-century landmarks in the patents that could help locate them on the landscape. Two constants stand out: the Great Road and Jamestown’s church. The Memorial Church sits atop several iterations of an earlier church structure, first erected ca. 1617 and in active use until the 1750s. The Great Road was originally a Virginia Indian trail, repurposed by the English colonists into a major thoroughfare linking Jamestown to the mainland.

Once transcribed and translated, the documents were handed off to the archaeology team. Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo has been the lead researcher for this aspect of the work, but many others—especially Dave Givens, Mary Anna Hartley, and Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford—have contributed. Using a geographic information system (GIS) program, the team has searched for features identified through archaeological work or GPR that correspond to boundary lines or markers described in the patents. This has been challenging, as the patents often reference other properties or long-gone markers. In addition, the Island itself has changed much in 400 years. Several hundred feet of shoreline have been lost to erosion, and the effects of climate change threaten to erase many more areas. This makes patents that rely on the James River as a reference point particularly difficult to locate.

Despite these difficulties, the team has been able to precisely locate several parcels. The most notable is the Churchyard, whose northern boundary was marked first by postholes and then by a large ditch. The team will be building off of these moving forward — property boundaries often stay relatively stable through time, even as parcels change hands — and they are hopeful that many more patents can be located. In the meantime, the team will keep digging. With every new structure unearthed or posthole uncovered, we gain another clue to help us learn who lived where. Stay tuned for updates as this research is ongoing.

related images

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber gives a tour of the burial excavations.

- The burial structure before being clad with plastic

- Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown always measures twice before cutting boards for the burial structure.

- The archaeological team split time between excavating and building the burial structure.

- The archaeological team prepares for the day’s work at the burial excavations.

- The archaeological team covers the burial structure in plastic.

- The burial structure just after sunrise

- The archaeological staff staples the plastic covering to the burial structure frame.

- The burial structure. Archaeologists and volunteers explain the excavations to visitors.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo points to one of the mud and stud structure postholes inside the burial structure.

- Senior Staff Archaeologists Sean Romo and Mary Anna Hartley examine a posthole that cuts one of the burials.

- Director of Archaeology David Givens discusses the next steps of the burial excavations with Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown. Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley conducts excavations and Senior Staff Archaeologist Dr. Chuck Durfor photographs one of the features.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Dr. Churck Durfor photographs features in the burial structure while Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo carefully scrapes away soil just south of one of the burials.

- The archaeological team at work in the burial structure. Pictured are (L-R) Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley, Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown, Senior Staff Archaeologist Dr. Chuck Durfor, Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford, and Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo.

- The palisade wall cutting through two of the burials. The post molds of the individual logs are scored to make them easier to see.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley excavates the palisade wall that cuts through two of the burials. She has scored the post mold of each log to make them easier to see.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford records the exact location of one of the features in the burial structure. This information will be added to our digital map of archaeological features.

- A 360 degree view of the archaeologists involved in the 2023 burial excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid holds a partial Virginia Indian pipe stem found during the burial excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid holds a projectile point found during the burial excavations.

- A close-up of a projectile point found during the burial excavations.

- A sherd of Virginia Indian pottery found during the burial excavations

- A partial Robert Cotton pipe stem found at the burial excavations

- The sword being conserved by Senior Conservator Dan Gamble. It’s inside the air abrasion housing where Dan is removing corrosion to reveal the iron underneath it.

- The spoon found in the Governor’s Well. Senior Conservator Dan Gamble is removing corrosion to reveal the shine of the tin beneath it.

- Conservator Chris Wilkins is featured on the daily Lab Cam, conserving artifacts found in the Governor’s Well.