Ongoing Analysis and Conservation of the Spoon from the Governor’s Well

Excavations on the Governor’s Well uncovered many incredible artifacts, like a sword, two sword hilts, leather shoes, and more. Thanks to the live Well Cam and social media, our followers were able to witness the moment of discovery and learn about these artifacts in real time. But the work doesn’t stop there. Now that these items have moved to the lab, they’re undergoing cleaning and conservation, and the curators are diving into research to learn more about the artifacts themselves. This is the time when our initial identifications may change based on what we can uncover by studying the artifact!

With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at the spoon from the Governor’s Well. The conservation and curatorial team have been looking into the shape, the material, and the mark on the spoon to better understand when it was made and by whom, and how to best proceed with conservation of this amazing artifact.

The shape:

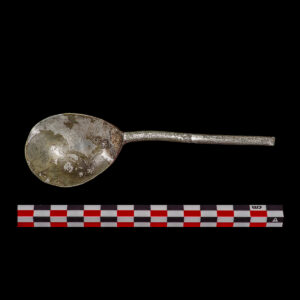

This recent find is a complete spoon with a slip-top handle. The handle shape, with the end cut at an angle is sometimes referred to as “slipped in the stalk.” This term comes from a 1498 will that describes silver spoons as “slipped in lez stalkes.” Slip-top spoons typically have hexagonal-sectioned stems and fig-shaped bowls, although the shape of both changed slightly from the early to the mid-17th century. Our artifact has a fig-shaped bowl and a hexagonal-sectioned stem, indicating that it dates to the fort period years. This handle style was very popular in 15th, 16th, and early 17th century London, perhaps because it was a simple and relatively cheap form to produce.

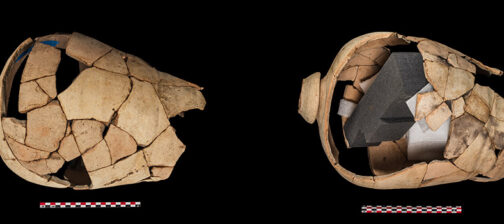

Spoons like this one were cast in a clay or stone mold. As the metal cooled, it could be handled, worked to shape, and stamped with a maker’s mark, owner’s initials, or both. The spoon from the Governor’s Well was imported to Virginia, as the earliest evidence of local metallic spoon-making comes from a ceramic mold made from local clay found at Martin’s Hundred, on a site dated ca. 1623-1645.

The spoon measures 151mm in overall length, with the stem measuring 93mm long, and the bowl 60 mm long. The handle is slightly bent, which accounts for the discrepancy with the overall length. The bowl measures 44.5mm wide at its widest point. This size is similar to slip-top spoons recovered from riverside excavations in Southwark, London, recorded by Geoff Egan in “Material Culture in London in an Age of Transition: Tudor and Stuart period finds c1450-c1700 from excavations at riverside sites in Southwark, London,” published by the Museum of London Archaeology in 2005.

The material:

Slip-top spoons were made of silver, pewter, and other copper alloys. Sometimes these alloys were referred to as “latten;” however, there is no comprehensive analysis indicating the exact elements comprising historic latten spoons, and no standardized recipe for latten used in spoon-making has been found. Because spoons historically referred to as “latten” are nearly always composed of copper alloyed with other material, we refer to these spoons as copper alloy, until further analysis can be done.

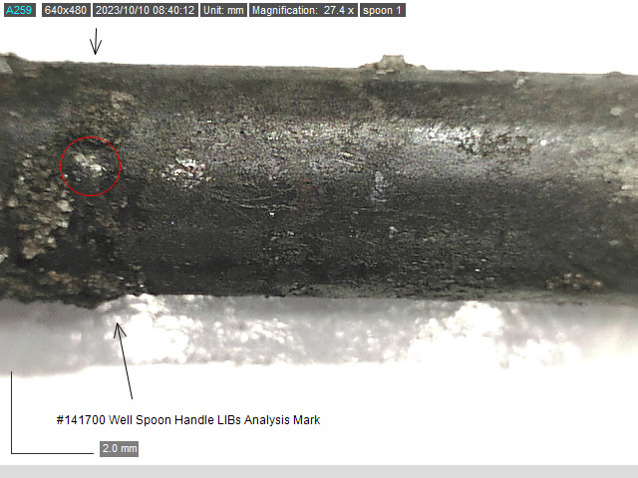

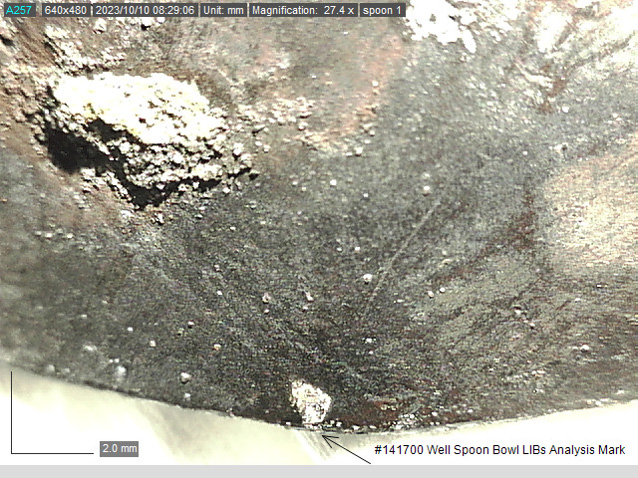

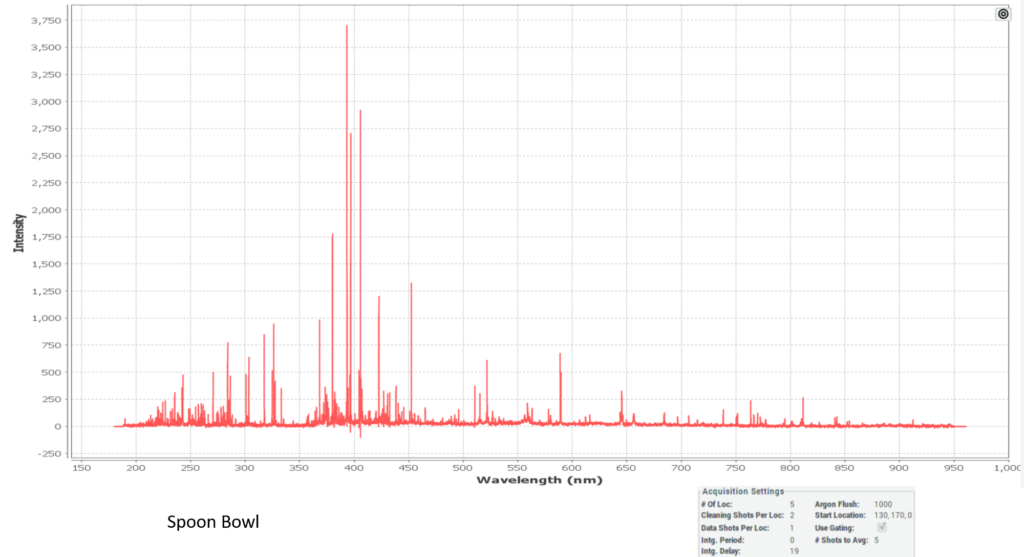

The percentages of the elements used to make metallic spoons varied in the 17th century. Because our spoon looks visibly similar to other artifacts made of silver, we wanted to securely identify its composition and decided to analyze it using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy, or LIBs for short. The LIBs analyzer is a handheld unit that fires a laser beam at the surface of a material, causing a microscopic explosion. Any atom in that explosion sends out photons at specific energies. Measuring the photons allows us to identify elements present in the material. This analysis told us not only the material make-up of the spoon, but also helped us determine how to proceed with conservation.

We analyzed two cleaner-looking areas of the spoon body, one site on the handle and the other on the bowl. Elements present included: calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), sodium (Na), aluminum (Al), rubidium (Rb), silicon (Si), potassium (K), strontium (Sr), tin (Sn), copper (Cu), and lead (Pb).

The first eight elements listed reflect sediment present on the surface of the spoon, since it had yet to be cleaned in the lab. The detection of high amounts of tin, with smaller amounts of copper and lead, and the absence of silver indicated that the visible silver-colored metal is actually tin, and the base metal body is possibly a leaded copper alloy created for casting the spoon. To reduce damage to the artifact during this analysis, we penetrated to–but not through–the tin coating with the analytical laser. Understanding the outer coating allows us to proceed with an appropriate conservation treatment for tin. After a more thorough cleaning, we can further analyze the base metal body.

The mark:

The circular-shaped maker’s mark on the spoon is a heart within a circle, flanked on either side by the letter “I.” This mark is recorded in a 1908 publication “Old Base Metal Spoons with Illustrations and Marks” by F.G. Hilton Price. Price’s research provides short descriptions and illustrations of spoons of every type in his personal collection, in the collections of other individuals, and in collections from a number of well-known English museums.

Unfortunately, the names and marks of members of the Worshipful Company of Pewters, chartered in 1473/4 by King Edward IV, were lost when the registers burned in the Great Fire of London in 1666. However, Price recorded that a pewter slip-top spoon with the same maker’s mark found on our artifact dated to the 16th century.

This style of mark is not uncommon. In fact, there are a number of marks just like it, but with different initials. The use of the heart is unclear. By the 17th century, the heart shape we know today was commonly associated with love, but the use of it in a maker’s mark may have been simply decorative or symmetrically pleasing.

In the 17th century, the letter “J” was still relatively new to the English alphabet and the letter “I” was often used to represent the initial of someone with a name that began with “J.” Based on other identified spoon marks in which this is the case, it seems likely that the individual who made the spoon had a first and/or last name that started with the letter “J.”

After excavation and the above detailed material analysis, the spoon underwent conservation. This process took about a month and involved mechanical cleaning in which conservators used brushes and a scalpel to remove layers of corrosion product. Once corrosion and other debris was removed the spoon was soaked in ethyl alcohol to remove oils from handling the artifact and lastly coated with an acrylic solution to protect it into the future.

- Governor’s Well spoon after conservation — front

- Governor’s Well spoon after conservation — back

We’ll continue to do more research, but for now, we believe this slip-top tinned spoon may have been purchased in London before getting passed on a ship to Jamestown, where it would somehow find its way to the bottom of a well.

Click here to see other styles of spoons found at Jamestown.