The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists have completed the disinterment of three individuals from the 1607 burial ground. Located inside the southwest corner of James Fort, approximately 36 burials have been located here. John Smith stated that 50 colonists died between May and September 1607, and they were buried inside the fort’s walls as instructed by the Virginia Company of London so as to hide their dwindling numbers from the Virginia Indians:

“Above all things do not advertize the killing of any of your men, that the country people may know it; if they perceive that they are but common men, and that with the loss of many of theirs, they may deminish any part of yours, they will make many adventures upon you.”

Charters of the Virginia Company of London1

Samuel Yonge, prime mover and engineer of the seawall that saved much of James Fort from eroding into the James River, writes that in 1896:

“It is credibly stated that when the bank thus exposed was undermined by the waves, several human skeletons lying in regular order, east and west, about two hundred feet west of the tower ruin were uncovered. On account of their nearness to the tower it seems quite probable that the skeletons were in the original churchyard. One of the skulls had been perforated by a musket ball and several buckshot, which it still held, suggesting a military execution. Soon after being exposed to the air the skeletons crumbled.”

Samuel Yonge2

Yonge’s seawall is still protecting the burial ground and the rest of the fort today. But his last sentence speaks to one of the reasons why we continue to disinter colonists from the burial ground. Prior to 2006, these burials were protected by several feet of soil in the form of Confederate Fort Pocahontas‘ earthworks. The Confederates (and the enslaved workers forced to do much of the work) unknowingly built the fort on the same high ground that James Fort was constructed on over 250 years earlier (though they knew they were close as colonial weapons and armor were found during the latter fort’s construction3). From 2003 to 2008, in an effort to reach James Fort’s archaeological remains underneath, Fort Pocahontas’ earthworks were excavated, using the same methods and care the team employs for the excavation of 17th-century features. Little did they know that they were also getting close to James Fort’s first burial ground in the process. Now there exists only two or three feet (depending on the individual grave) of soil between these human remains and the rain above. This environmental change exposes the burials to a multitude of wet/dry cycles, which is extremely detrimental to human remains and the information the remains contain about the individuals and their lives. That is why they are committed to excavating three burials from the 1607 burial ground every fall for preservation, scientific research, and eventual reinterment in an environment better protected from harmful environmental processes.

The excavation of the three individuals is complete and their remains are now in the Rediscovery Center, the bones cleaned and treated in a manner that will preserve them for research and reinterment. As Yonge noted, an uncontrolled exposure of human remains to the elements can cause them to quickly deteriorate. Senior Conservator Dan Gamble explained that the conservation team uses a controlled drying method where bones are kept in plastic bags, maintaining the humidity so that moisture in the bones evaporates at a slow enough pace that the structural integrity of the bones is maintained. The integrity of the bones is important for further research.

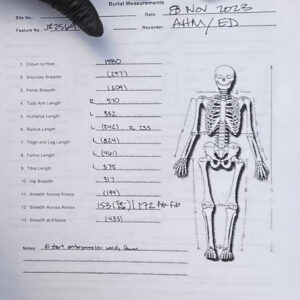

Based on preliminary analysis and the archaeological context, in a burial ground believed to have been established by the first 104 men and boys who arrived on the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery, the remains are thought to be male. However, the youngest individual is too young to have begun to show the skeletal traits that osteologists use to distinguish between men and women. Two of the individuals were teenagers, with unfused growth plates at the ends of their bones. The youngest individual had second molars (which are developed by 12 years) but no visible evidence of wisdom teeth, and at a little over 4 feet tall was also unusually short for a child in their early teens. The other immature individual was an older teenager, with wisdom teeth just visible inside the bones of the jaw. The oldest of the three was an adult man who was likely fairly young, but adults who have finished growing and don’t yet have degenerative bony changes related to age are the most difficult for osteologists to give precise age ranges for. Further laboratory analysis may reveal that he was older than currently suspected, but hopefully will narrow the current cautious estimate of 20-40 years! The man and the older teen show evidence of having been shrouded based on their body positions, with collarbones rotated and legs close together. A copper alloy aglet was also found on the man’s feet, one of the places where burial shrouds were often tied closed. The youngest individual did not show any evidence of wrapping and the shape of the grave and positioning of the body within the grave were the least careful of the three, possibly an indication of social status.

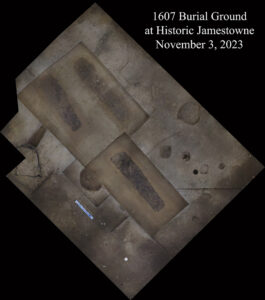

The archaeologists worked in teams to exhume the individuals. Director of Archaeology David Givens led the team that excavated the adult. Other members of the team included Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown. Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley led the team who disinterred the youngest colonist. Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch were members of Mary Anna’s team. A third team including Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford, and Archaeological Field Technicians Josh Barber and Ren Willis was led by Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo. This team exhumed the teenager. As mentioned in October’s update, the excavations in the burial area also led to the discovery of three postholes of a previously undiscovered early fort-period building. This month one of the post molds of this mud and stud building was excavated and a lead die was found inside, one of only seven lead dice in the collection. Dozens of dice have been found in and around the fort since Jamestown Rediscovery began its dig in 1994. The archaeologists are now backfilling the site to protect the archaeological resources.

Dr. Ashley McKeown, a forensic anthropologist from Texas State University and a long-time consultant for the project, joined the team again to help excavate and analyze the remains of the individuals. Dr. McKeown has worked with Jamestown Rediscovery repeatedly since the early years of the project, applying her expertise to look for physical evidence of age, sex, health, activity patterns, ancestry, and possible anomalies. Dr. McKeown again worked with Jamestown Rediscovery’s Assistant Curator Emma Derry on these individuals. Similarly to the field archaeologists, the entire conservation and curatorial staff wore suits, gloves, and masks while working on the remains to prevent their DNA from contaminating that of the disinterred individuals. Access to the lab during this time was strictly limited as well; only those folks working on the remains and who were properly suited up can get close to them.

Jamestown Rediscovery is fortunate to partner with Drs. Deborah Bolnick and Raquel Fleskes of the University of Connecticut, both biological anthropologists who are leading researchers in ancient DNA (aDNA). At the Bolnick Lab at UConn, Dr. Fleskes will extract and analyze DNA from these individuals as she did for the three who were excavated last year. The DNA extracted from the three individuals exhumed in 2022 was of remarkably good quality, with a low level of contamination by modern DNA, an indication that the precautions the archaeological, conservation, and curatorial teams take are effective in preventing their DNA from “muddying the waters.” DNA extraction and analysis will allow the team to gain clues as to where folks came from, what they looked like, and possibly even who they were. Though a rare occurrence, positive identifications are one of the goals of this process, and the team is working to track down modern descendants of some of the settlers buried at Jamestown to compare DNA results. Dr. Fleskes also traveled to Jamestown during the excavations to lend her expertise during the course of that process.

Work continues at the clay borrow pit, a source of clay for bricks in the late 17th century. Clay sourced here likely formed many of the bricks that still survive a few feet away as part of the 1680s Church Tower. The team has removed all of the plow scars from the feature, evidence of the centuries of farming that occurred on the island both during and after its time as Virginia’s capital. A five by twelve foot section of the pit is being prepared for excavation, with the goal of determining the pit’s depth and searching for artifacts that will help date the feature more precisely. Eventually an entire corner of the pit will be excavated with the same goals in mind. Sections of two zig-zag ditches to the west of the pit — perhaps property boundaries — will also be excavated. The ditches have their zig-zag shapes because they mirror that of the split-rail fences that accompanied them. Hopefully there will be artifacts or other archaeological evidence found in the ditches that will help date these as well. If these are in-fact property delineators then they could be helpful in Jamestown Rediscovery’s goal to place property (and people) on the modern landscape.

Research on the artifacts found in the Governor’s Well continues. The well contained several large stones, some of which were so large that they had to be removed with a pulley. Three geologists from William & Mary, Drs. James Kaste, C. Rick Berquist, and Dominick Ciruzzi are currently analyzing them in an effort to determine their type and location of origin. A wooden foundation for the well was found by the archaeological team when they reached its bottom. The team will excavate the remaining courses of brick and then excavate the wooden ring, tentatively in early 2024. James Delgado, of SEARCH, an archaeology firm that specializes in recovering underwater artifacts, has offered his help in the ring’s excavation.

In the lab, Conservation Intern Jackie Bucklew is mending an Essex post-medieval blackware vessel, a possible posset pot. The partial vessel has been in the collection for several years, its pieces having been found all over James Fort, including in both the first and second wells and the blacksmith shop/bakery. Jackie’s efforts were necessary because more pieces of the vessel were found since the original mending, including in the spaces between existing sherds. Jackie uses acetone to weaken the adhesive holding the pieces together until it has a gummy consistency and the sherds can safely be pulled apart. Then the new pieces are added using the same reversible adhesive.

Curatorial Intern Lindsay Bliss is using a water sieving process to capture artifacts from the Governor’s Well. Lindsay is using water and a set of sieves with increasingly-small holes to separate artifacts based on size. The hope is to capture organics such as seeds and maybe even a few more tobacco seeds to add to the collection. The sieve holes vary in size from 2 millimeters all the way down to 250 microns, which would capture tiny objects such as tobacco seeds. To give an idea of a tobacco seed’s diminiutive size, each of them weighs approximately 1/350,000 of an ounce. As tobacco was central to the survival and flourishing of the colony and the Governor’s Well was used during the 1610s, the latter half of which saw John Rolfe’s strain of tobacco become popular both at home and abroad, we are interested in capturing any such seeds to study the plant’s change over time.

- Charters of the Virginia Company of London; Laws; Abstracts of Rolls in the Offices of State.

- Yonge, S. H. (1907). The site of old “James Towne,” 1607-1698: A brief historical and topographical sketch of the first American metropolis ; illustrated with original maps, drawings and photographs, 72.

- Yonge, The Site of old “James Towne,” 32.

related images

- The burials excavation team. Front row (L-R): Caitlin Delmas, Natalie Reid, Mary Anna Hartley, Ren Willis. Back row (L-R): David Givens, Dr. Ashley McKeown, Anna Shackelford, Hannah Barch, Emma Derry, Sean Romo, Dan Gamble, Gabriel Brown.

- The team preparing for the burial excavations.

- Inside the burial structure

- Volunteer Cynthia Garman-Squier and Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber screen for artifacts in the soil excavated from the 1607 burial ground.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber examines the lead die found in one of the mud and stud post molds in the burial excavation area.

- An example of burial measurements of one of the individuals while still in situ.

- The burials excavation team silhouetted at sunset

- The burial excavation area after the completion of the project and just before backfilling

- Backfilling the burial excavations. The Gator is used to help pack the soil down.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley describes the backfilling process at the burial site as the archaeological team fills it in at left.

- Samples from the Governor’s Well after water sieving by Curatorial Intern Lindsay Bliss. The separated samples are sorted by ascending sieve hole size from left to right (250 microns, 500 microns, 1mm, 2mm).

- Excavations at the clay borrow pit

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis sorts for artifacts at the clay borrow pit.

- The burial structure at sunset