Archaeology is advancing our understanding of a ditch thought to date to 1608 as excavations on a segment of it near completion. A few feet to the north, ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and excavations of multiple 10 x 10 foot squares have uncovered several pits and postholes as well as a trench running east/west. The team has also been busy designing, building, and moving a well ring that will protect them as they dig down into the well’s builder’s trench. In the lab, some unique decorated buttons are being conserved, found in James Fort’s first well and thought to belong to the same doublet. The team also opened the glass floors in the Memorial Church to clean the Knights Tomb, portions of the earlier churches’ foundations, and the floors themselves. Members of the curation team have begun to use our flotation machine to process over 300 soil samples from 2012 to the present. Visitors can watch them work on the Seawall near the Dale House Café. In the Vault, ongoing cataloging efforts have included processing of more mica glass from a lantern and a small crucible found near the Memorial Church.

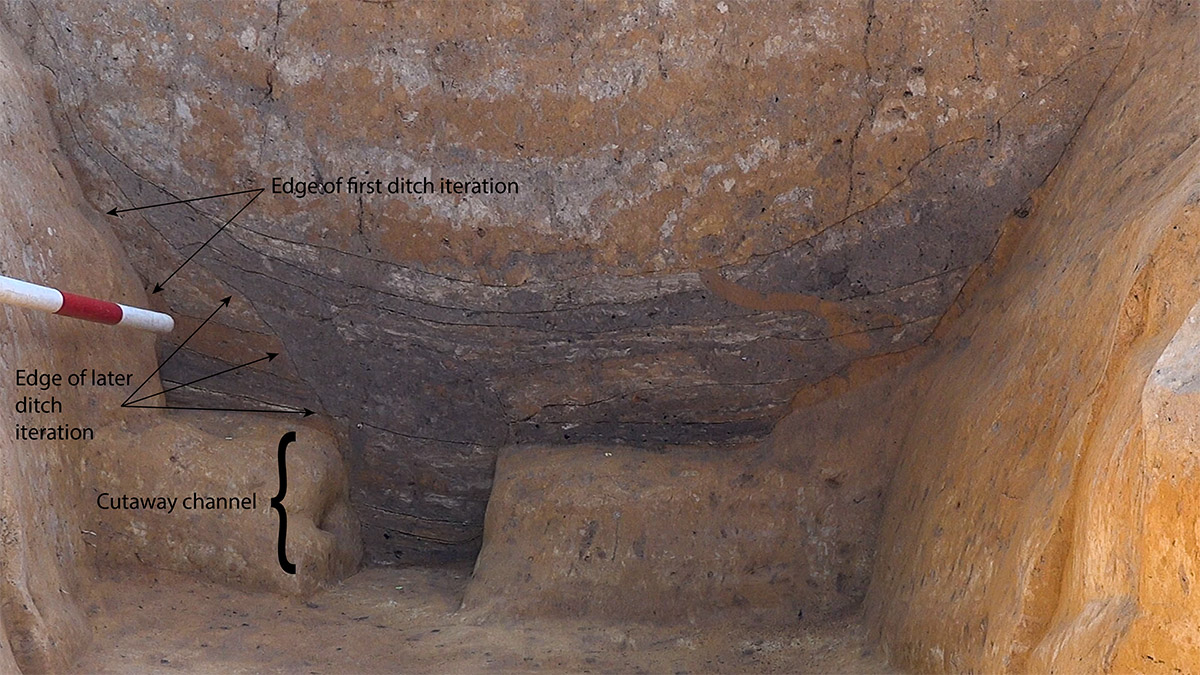

Just outside James Fort’s northern bulwark, a section of the 1608 ditch has been excavated all the way to the northern limit of the excavation square and then all the way down to the subsoil. The construction of the road that separates these excavations from the squares just to the north appears to have destroyed about a foot of the ditch’s top. As archaeologists Anna Shackelford, Caitlin Delmas, and Natalie Reid scraped away the ditch and inched northward, its layers told a story of use, reuse, and deliberate filling in. The ditch was initially a flat-bottomed one, and it had a small, centrally-located cutaway channel, perhaps used for drainage. There was a large charcoal and scorched daub (a clay composite used for building walls) deposit across the entire width of the ditch on the southern side of the road. This may indicate that a mud-and-stud structure burned nearby or that the ditch was intentionally filled with the charred structural remains. The ditch was later modified as evidenced by darker soil layers that cut through the earlier layers. The colonists purposely redug the ditch, whether purely for maintenance or to repurpose it for something else. This second iteration of the ditch had a more gradual slope than the earlier version and the ditch moved a few inches to the east as a result of the modifications. Interestingly although the initial ditch’s floor and channel stopped a few feet from the road, it’s charcoal-laden fill continued to the south. As the ditch was open to the elements, rain washed soil into it. These thin wash layers mark both the initial and subsequent versions of the ditch.

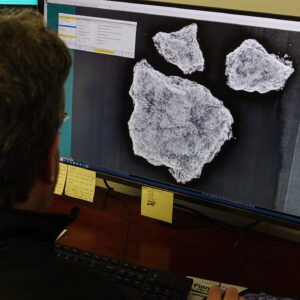

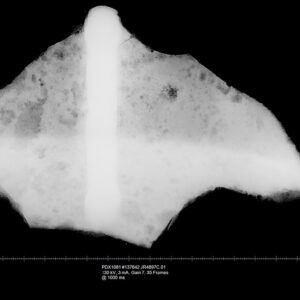

The ditch was probably in use for the better part of two years. If this ditch is indeed the part of the flag structure seen on the Zuñiga map of June 1608, then it was probably constructed in the spring of that year. The Zuñiga map shows the ditch but a map by Robert Tindall from two months earlier does not. The upper layers of the ditch contain an intentional clay fill similar to those found in other fort period structures thought to be associated with Lord De La Warr’s cleanup of 1610. When the baron arrived in June of 1610 just after the “Starving Time” of the previous few months, he ordered the colonists to “cleanse the Town.” This resulted in the clay capping of several of the fort’s early subterranean features, including the first well that was filled with trash prior to being covered over. The clay layers at the top of the ditch may have been part of this process. The ditch has yielded quite a few Virginia Indian artifacts including sherds of pottery and lithics but there has been very little in the way of European artifacts. This is consistent with other early features that show evidence of Indian use of the site prior to the arrival of the English, but because the ditch was early (the area hadn’t previously been used by the colonists) and because it was probably filled in after only two years of use, there just weren’t as many opportunities for the colonists to drop or discard things as there would be for later or longer-lived features. This being said, in addition to the many sherds of native ceramics and rock flakes found here, a large flat iron object was discovered here this month, as was a shard of glass. The iron object has undergone multiple X-ray scans that unfortunately indicate there is very little of the original iron left; what remains is largely corrosion (“rust”). So while the team is trying to identify the artifact, at this point it appears they will not be able to conserve it without irreparably damaging it.

Across the road to the north, archaeologists Hannah Barch, Gabriel Brown, and Josh Barber continue to uncover new features and early artifacts. Ground penetrating radar (GPR) indicates another subterranean feature 18 feet to the east of the one discovered earlier this year. They appear to be similar in shape and size. The slumping soil of these features points to a pit rather than a large posthole. Postholes are purposely (and densely) filled in once the wooden post has been installed so as to provide stability whereas a pit tends to be less tightly packed once it has outlived its usefulness. A GPR survey of the initial, western pit gives indication that there might be debris inside. Multiple postholes have been found during these excavations. It’s unclear as of yet if the postholes are related to one another but the plan is to open additional squares to see if more turn up. We also don’t yet know the age of these features or if they are part of a single large structure or multiple smaller ones. A ditch runs east-west through these excavations with cobbles and bricks protruding out of it. These artifacts are associated with the ditch but some have been pushed out of it by the farming plows that worked in this area, as evidenced by the multiple plow scars found in these squares. As with the other features here, the ditch’s age and purpose are currently unknown. Hopefully further excavations deeper into these squares and the opening of adjacent ones will shed light on these features. Tobacco pipes made of both Virginian and European clay were found here this month as well as a Virginia Indian lithic blade or projectile point. A partial iron cauldron turned up, as did sherds of Chinese porcelain, a sherd of a Bartmann jug, and some 20th century pennies.

Construction is complete on the first stage of the well ring, a wooden circle that will protect the archaeologists from cave-ins as the excavations of the 1610s well progress downwards into the earth. Archaeologists David Givens, Sean Romo, Anna Shackelford, and Gabriel Brown designed and built the structure, aided by the experience of past well excavations. Once the initial portion of the ring was complete, it was necessary to move it to the archaeology shed to free up the parking spots it had been taking up during construction. The team built a makeshift sled and then placed a series of logs in front of the sled and pushed it down the gravel road to the shed. Once a log had been traversed, it was picked up from the rear and placed down in front of the sled again. The team was quite exhausted after repeating this process over and over with the eight logs at its disposal. Once the preparatory excavations at the well site are complete, the same process will be used to move it there.

In the lab, Senior Conservator Dan Gamble is conserving four 17th-century copper-alloy doublet buttons. Having a flat decorated head and a long, flat, and thin shank, these are the only four of this type in the Jamestown collection. All four were found in the fort’s first well and may have belonged to the same garment. The head bears a cross-hatch pattern that was impossible to see prior to Dan’s conservation work, encased as it was with corrosion. Next door in the Vault, the team has recently cataloged a small early 17th-century crucible found near the Church Tower. Although only the base was found, it is markedly similar to another, larger, example in our collection. The team has also cataloged additional mica pieces used as glass for a lantern. These almost certainly belong to the same lantern as the other mica panes found in the fort’s second well.

Curator Leah Stricker and intern Lindsay Bliss have begun using the flotation machine in earnest now that it has been repaired. There are over 300 soil samples from various parts of the site that are in the queue for this process. Working on the Seawall close to the Dale House Cafe, either Leah or Lindsay will be using the flotation machine Tuesday through Thursday, weather permitting, until all the samples have been processed. The process uses water to separate the sample into a light fraction — the material that floats — from the material that doesn’t, the heavy fraction. The light fraction can contain organics such as burned wood or seeds and tiny objects that require investigation through a microscope for identification.

In the Memorial Church, the conservation team cleaned the Knight’s Tomb and the glass-covered areas of the earlier churches’ foundations. Although glass flooring over the Tomb and the foundations allows visitors to see the archaeological resources underneath, it also reveals spider webs, dead insects, and the like that detract from the view. Cleaning the floors and the objects beneath was the easy part of the task; lifting the windows that weigh several hundred pounds took a group effort. The Knight’s Tomb, thought to be the resting place of Sir George Yeardley, knighted by King James I himself and twice governor of Virginia, has been robbed of its brass inlays and the robber’s pry marks are visible on the Belgian black limestone. The glass floor on the southern side of the church permits a view of the foundations of both the 1617 and 1639 churches. A total of four churches were built where the Memorial Church stands today.

dig deeper

related images

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid explains the excavations of the 1608 ditch and 1610s well during an archaeology tour.

- A profile of the 1608 ditch. Part of the well’s builder’s trench is in the foreground.

- An iron object found in the 1608 ditch

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid hands an iron object found in the 1608 ditch over to Director of Archaeology David Givens for examination. Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo is at right.

- Some of the artifacts found in the 1608 ditch near the well. Several sherds of Virginia Indian pottery can be seen along with various lithics.

- A volunteer describes the well and ditch excavations to some visitors. The excavations to the north are visible in the background.

- Archaeologist Hannah Barch gives a tour of the well and ditch excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid excavates the charcoal layer from the 1608 ditch near the well.

- A view of the excavations looking south

- A view of two adjacent squares in the north field. The east/west ditch is clearly visible in the foreground as is the pit feature near the center in the background.

- A couple of sherds of Chinese porcelain found during excavations in the north field.

- Archaeologists Caitlin Delmas, Hannah Barch, and Josh Barber perform a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey in one of the excavation squares in the north field.

- A sherd of a Bartmann jug found in the north field excavations. Part of the Bartmann’s beard is visible.

- Some European pipes found in the north field excavations.

- An X-ray of the partial iron cauldron found in the north field excavations.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber uses window screen to look for tiny objects that would fall through other screens.

- Archaeologists Gabriel Brown, Anna Shackelford, and David Givens design the well ring.

- The well ring begins its journey to the archaeology shed.

- Archaeologists Anna Shackelford, Sean Romo, David Givens, and Gabriel Brown discuss the well ring construction.

- One of the doublet buttons before conservation. Corrosion conceals the decoration on its head and the thin shank.

- The base of the small crucible found near the Memorial Church is in the foreground. A larger example found earlier stands behind it.

- Mica that probably served as glass panes for a lantern. This mica was probably part of the same lantern as other mica in the collection.

- Curator Leah Stricker on the Seawall using the flotation machine.

- Curator Leah Stricker examines the heavy fraction of a soil sample near the Monument Church. Brick and plaster are prevalent.

- A light fraction after the flotation process

- The heavy fraction (left) and light fraction (right) of a soil sample after flotation.

- Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin cleans the Knight’s Tomb ledger stone.

- A closeup of the Knight’s Tomb ledger stone showing pry marks from the robbery of its brass inlays.