Shovels, pickaxes, and trowels are hard at work all over Jamestown. Work continues on an early 17th-century well found just outside James Fort’s north bulwark. Across the walking path to the north, new excavations have begun that have revealed the presence of a large, square feature, confirming data from an earlier ground-penetrating radar survey. Near the Colonial Dames of America gate, more excavations have been opened in preparation for the installation of a new sign, revealing some potentially early features. In the 1680s Church Tower, archaeologists built a wooden floor to allow visitors inside again and protect the archaeological resources underneath during the installation of a glass roof. Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo and Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins examined the cask staves that lined a mid 17th-century well, measuring dimensions and looking for clues as to who made them and what for. Dr. Ashley McKeown, Jamestown Rediscovery’s Osteology Research Fellow, worked with Assistant Curator Emma Derry to examine the three burials excavated in October. The curatorial team is excited to have received the report on the analysis of botanical remains from James Fort’s second well. Five additional tobacco seeds and the collection’s first huckleberry seed were among the findings. Additional work in the Vault this month has focused on fossils and the iron buckle collection. The flotation tank is finally repaired and the curatorial team is happy to be able to resume processing flotation samples collected from around the site. Next door in the lab the team has figuratively gotten their hands dirty with the new X-ray detector and is refining their procedure for the backlog of artifacts needing to be X-rayed.

At the 17th-century well found last year, the team has daylighted the full circumference of the well’s builder’s trench. The construction of the well and its shape and size (and that of its builder’s trench) is similar to another well found in 2002 which dates to the 1610s and which yielded hundreds of artifacts. Construction of a wooden platform will begin in April that will allow visitors to watch the excavations first-hand. The platform (and the wooden ring to be installed around the well) will also allow our team to safely work in the space and protect its archaeological resources. Excavations continue in earnest on the 1608 ditch that was cut by the well construction a few years later. The ditch excavations have revealed a thick cap of solid clay on top, a characteristic found in other fort features thought to relate to Lord De La Warr’s orders to “cleanse the Town” upon his arrival in 1610. A notable amount of charcoal and daub exists in the ditch, perhaps artifacts from the chimney area of a building or rubble from a burned one. Very little in the way of artifacts has been found in the ditch, usually a good indicator of an early feature. In April a “well cam” will go online that will allow anyone with an Internet connection to join the moment of discovery. The well excavations are expected to last through the summer.

In the field across the walking path a ten foot by twenty foot rectangle has been opened up to explore a large feature that lies right in the middle. This feature was discovered using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and may be a storage pit or possibly a very large post hole. Led by Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford, the team is working to determine which of these interpretations is correct. Thus far, excavations have uncovered few artifacts, mostly small sherds of English pottery and tobacco pipes. A small ditch runs east/west through this area, its purpose and age as yet unknown. On the southern edge of these excavations ash, charcoal, and fire-reddened clay may indicate a nearby hearth. This area, just north of the fort, has yielded several promising GPR hits in the form of additional large rectangular footprints. Further GPR and “ground-truthing” via excavation will be done to investigate these in the months ahead.

A few feet to the east of the Colonial Dames of America gate, a new sign welcoming visitors is being installed. Because there are archaeological features everywhere on the island, a preliminary dig is being conducted to precisely place the sign where it won’t damage them. As the excavations progressed here the team did indeed find features, including several possible postholes and a pit. Ceramics, both European and Native American, were found in the plowzone above the features but no artifacts were in the layers containing the features themselves, a sign that they may be very early.

Inside the 1680s Church Tower, the archaeologists continue to prepare for the installation of a glass roof and a glass floor. These installations will protect the interior of the structure for decades to come. The new roof will be the first time the Tower has had a roof since the 18th century. The team constructed a new wooden floor that will allow visitors to walk inside the tower again and will also protect the archaeological resources during the roof’s construction. After the installation is complete, the team will dismantle their wooden floor and conduct thorough excavations inside the footprint of the Tower. The eastern palisade wall of James Fort goes right through the Church Tower’s footprint so hopefully evidence of that will be found when the excavations begin. After the excavations are complete the glass floor will be installed, allowing visitors to see the archaeological features for themselves.

Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo and Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins analyzed cask staves that once lined a mid-17th-century well inside the footprint of where James Fort once stood. The well was a narrow one — just two or three feet in diameter — and was lined with wooden casks stacked one on top of another. Sean and Chris were examining the staves to look for any marks that might indicate the name of the coopers who built the casks or what the casks initially contained. Unfortunately they were unable to find any such marks. They were also trying to determine the overall dimensions of the casks, in particular their height. The staves had survived because they were below the water line, in waterlogged soil preventing aerobic bacteria from consuming the wood. Above the water line, the archaeologists found stains where other staves once were. The well itself cut the footprint of the 1608 church, an indication of its later date.

Dr. Ashley McKeown, Jamestown Rediscovery’s Osteology Research Fellow, was on site for several days this month to work with Assistant Curator Emma Derry on the three sets of human remains that were excavated last October from the 1607 burial ground. This visit largely focused on the most well preserved individual, a 20-something male who had a shallower burial than the other two. This was likely the decisive factor in his state of preservation — the shallower, less-saturated soil surrounding him allowed for better drainage and less time that the bones were in contact with water. Ashley and Emma looked at the subtle things in bones that can tell age, sex, health, activity patterns, and hint at things like ancestry. This individual was about 5’7″ — tall for an Englishman of this time period. He was not the most robust individual; his height suggests he was well fed but his bones indicate that he was not particularly muscular. This may suggest that physical labor was not central to his livelihood. Additional analysis of the three individuals will occur in the months ahead.

The curatorial team has received the analytical report on a sample of the plant remains from the fort’s second well. Conducted by consultant Justine McKnight, her analysis revealed an additional five tobacco seeds, two strawberry seeds, squash rind fragments, and a huckleberry seed, the first known one in the collection. Additionally pine, maple, white and red oak wood, and acorns and hickory nuts were discovered by her methods. McKnight also noted the decreased biological diversity in these samples — stored in a refrigerator since 2006 — compared to samples from the same well that were analyzed years earlier. This is very valuable information — that biological deterioriation occurs in waterlogged, refrigerated soil samples — and gives a new sense of urgency for the analysis of our other samples from the second well. You can read McKnight’s report here.

Curator Leah Stricker has spent much of March working on the fossil collection. She is organizing and cataloging the collection, a number of which are the remains of ancient sea creatures. Among the animals is Chesapecten jeffersonius, an extinct mollusk that lived between four and five million years ago. Named in honor of Thomas Jefferson and being the state fossil of Virginia, these fossils are plentiful in the tidewater region of Virginia. Another interesting specimen is a limestone marl with a conglomerate of fossils throughout, including several examples of Chesapecten jeffersonius. Several whale fossils are in the collection, including ribs and a vertebra. Finally a number of megalodon teeth have been found by the archaeologists over the years. The megalodon was an ancient shark that could be upwards of fifty feet long when mature. These fossils were probably kept as curiosities by the colonists. Leah is also working to better organize and store the collection of iron buckles. Because storage space is finite in the Dry Room — a room kept at an ideal temperature and humidity to inhibit oxidation of iron artifacts — conserved examples of each buckle type are kept in boxes at the front of the drawer while similar examples are kept in bags in the rear of the drawer. Bagging the other examples saves space while still allowing access to the artifacts if a researcher needs to look at all examples of a certain type.

The curatorial staff is excited to have their flotation tank repaired. Flotation is a process by which objects of different densities are separated by placing them into a specialized water tank (Watch a video describing this process). There are over 300 flotation soil samples waiting to be processed. Each sample can take from twenty minutes to two hours to process depending on the type of soil. Sandy soil tends to go quickly whereas clay soil takes much longer. We are planning to do flotation on site this summer, so be sure to stop by the seawall and watch the process!

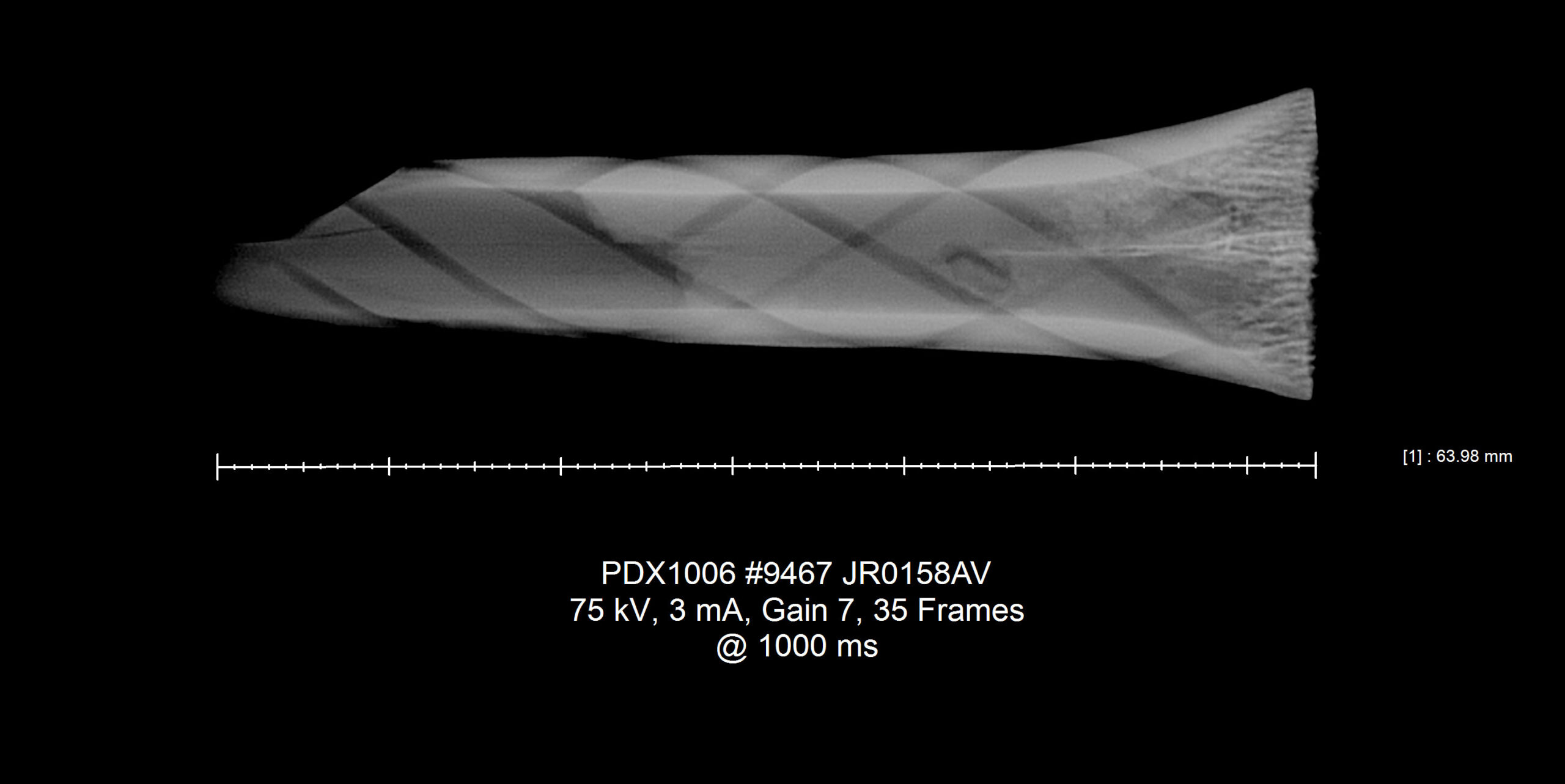

In the lab the conservation team is busy refining their X-ray process now that the new X-ray detector is installed and training is complete. Conservators Don Warmke and Dr. Chris Wilkins have been experimenting with various settings to see what works with artifacts of different makes and densities. The team is finding that objects can benefit from multiple x-rays when different areas of the object have different densities. A denser area may require a higher kV, but that might completely “see through” a less dense part of the object. This is frequently the case with the Jamestown collection when oxidation has occurred unevenly on an object or the object was not of uniform density to begin with.

dig deeper

related images

- The 1610s well and builder’s trench (dark circle around the well).

- A profile of the 1608 ditch as seen from the well. Wash layers and charcoal are visible.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas works to remove some of the layers at the excavations in the north field while archaeologist Eli Clem screens for artifacts.

- The archaeological crew at work at the excavations near the Colonial Dames of America gate (pictured at left).

- Archaeologist Gabriel Brown shares some of the artifacts found in the excavations near the Colonial Dames of America gate.

- Archaeologists Gabriel Brown and Eli Clem help to build a new floor for the Church Tower to allow visitors back inside.

- Curator Leah Stricker holds a limestone marl containing several shell fossils.

- Curator Leah Stricker holds a whale vertebra fossil.

- Curator (and archaeologist) Leah Stricker holds a megalodon tooth that she found during excavations in the Memorial Church in 2017. Fellow archaeologist Bob Chartrand was surprised (and jealous).

- The iron buckles in the Jamestown collection. The conserved examples in the foreground serve as representatives of others of their type that are in small bags at the rear of the shelf and in the shelf above.

- Some of the botanical artifacts found during Justine McKnight’s analysis. The soil from which she pulled her sample is in the bag at right.