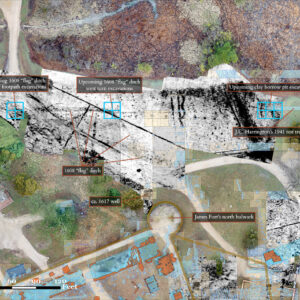

The 2023 Archaeological Field School is about to begin and these students will be excavating areas of great importance to the understanding of the 1608 “flag” feature depicted on an early map of James Fort. The Jamestown Rediscovery team has designated two new areas for the students to excavate that will hopefully give more form to the feature. Several yards to the east, the students will also be excavating a pit that served as a source of clay for a nearby brickmaking kiln. Attendees of this summer’s Kids Camp will continue the excavations at the pit a few days later. Work on the ca. 1617 well has been paused until after the Field School and Kids Camps are complete when the archaeologists can give the feature the attention it will require. The “Forensic Fridays” and “Inside the Vault” tours began this month, giving attendees a behind-the-scenes look at both the field and collections/conservation sides of the Jamestown Rediscovery Project. Out on the Seawall, the curation team continues their flotation work, looking for small artifacts from soil samples collected across the site. In the lab, analysis of Frechen pottery sherds has led to many new mends on a Bartmann jug over the past few weeks. The jug has three medallions and grows in completeness by the day. Also in the lab, mending of a large glass case bottle is nearly complete and the design and manufacture of a mount has begun. The renovated X-ray machine continues to get good use as a backlog of artifacts are scanned in an effort to create record shots of the artifacts in the collection.

This year’s Field School students will be excavating key areas of the “flag” feature found on the Zuñiga map of Jamestown from 1608. Now the logo of Jamestown Rediscovery, the map contains one of the few contemporary depictions of James Fort. What looks like a flag on the map has been proven through ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and excavations to be a ditch, determined to be a military fortification based on the ditch’s profile. GPR further indicates that the ditch turns to the west as the map suggests it should but then the scan’s results become murky when the ditch crosses the modern footpath and intersects Fort Pocahontas’s moat. The students will conduct excavations in these two key areas — the spot where the ditch begins its westward turn and the area just across the footpath. The hope is that these digs will provide evidence for the ditch’s form and function and also give clues to its possible relation to other nearby features.

Over at the ca. 1617 well, the team has built a viewing platform and installed a wooden protective ring beneath it. The platform will allow visitors to join the moment of discovery, observing the excavations as they progress into the well below. Using the same methods they employed to transport the wooden protective ring to the archaeological shed, the team moved the ring to the well and slowly lowered it into the custom gap left in the observation platform. This ring will protect the archaeologists from cave-ins of the surrounding soil as they dig down. Another identical ring will be built and placed on top of the existing one when the depth of the excavations warrants it. Excavations of the well and surrounding builder’s trench are on hold until August/September when the Field School and Kids Camp are completed. Only then the team will be able to give the well their full attention as they dig down into the water table, using pumps to fight the never-ending encroachment of water and explore the depths below. Hopefully the colonists used this well as a trash pit like they did others when the water was no longer drinkable. The trash (artifacts) will need to be examined for organic materials such as leather, wood, and seeds. Organic artifacts need to be quickly resubmerged in tanks to prevent drying out and for protection against the air-breathing bacteria that would consume them.

Both the Field School students and the Kids Camp campers will be excavating the clay borrow pit that was a source of clay for multiple brick kilns nearby. Thousands of bricks are thought to have been sourced from the pit, with a large number of them still existing in the form of the 1680s Church Tower just to the south, the only surviving above-ground 17th-century structure at Jamestown. Archaeologist J.C. Harrington and his team excavated a test trench here in 1941, and the Jamestown Rediscovery team want to expand on his work by removing his backfill, viewing a profile of the historic layers, and then excavating six new 10×10 squares in and around his work. This brickmaking operation was active in the latter half of the 17th century and the excavations here will hopefully give us new insights into this transition period of Jamestown’s history. Harrington’s reports indicate that his dig here was artifact-rich, so the students and campers screening the soil will hopefully have many interesting finds. There is hope that these new squares may contain features that relate to the ongoing excavations just to the west . . . that they might contain postholes and pits similar to those seen there and could help establish patterns that shed light on their form and function.

At the north field dig, the east/west ditch discussed in April’s update should pop up again in the upcoming excavation area where the “flag” feature bends and heads west. GPR suggests the presence of the ditch in the area so the Field School students’ excavations in these new squares should reveal additional sections of both ditches. The east/west ditch is markedly narrow, unusually so for a ditch. There is some thought that it may have been a palisade but it is too early to tell. As is the case with the dig at the clay borrow pit, there is hope that additional postholes and pits may turn up in the new Field School squares here that are similar to those found in the existing north field excavations.

In addition to shovel-in-ground archaeology, the Field School students will be conducting GPR surveys to the north and east of James Fort’s northern bulwark. This area is a giant hole in the GPR data, and while the students will be providing a much-needed contribution to the understanding of the archaeological resources at Jamestown, they’ll also be learning a tool that is increasingly integral to the archaeological field. GPR is a non-destructive way to “see” features under the surface and can provide guidance to archaeologists as to where (or where not) to dig. As excavations are necessarily destructive, GPR can give archaeologists the ability to record features and then, if traditional excavations are unnecessary, choose not to dig. This can also save excavations for future archaeologists, whose tool set will likely be better than that available today. The concepts learned and hands-on experience with GPR will be helpful to the Field School students should they pursue a career in the archaeological field.

Behind-the-scenes tours have begun this month that allow visitors to get a look at Jamestown’s archaeology and collections typically reserved for the staff. The “Forensic Fridays” tour is led by a senior forensic archaeologist and includes a lecture inside the Memorial Church detailing some of the cold cases being investigated by the archaeological team. When skeletal remains are found, the team uses many different disciplines to determine age, sex, status, disease, and place of origin. Advances in DNA technology are also being used to tie the colonists buried at Jamestown to living individuals. Weather permitting, a behind-the-scenes tour of the current excavations will follow the lecture. More information and tickets for the “Forensic Fridays” tour can be found here. For those wanting to learn how artifacts are conserved and researched after being brought in from the field, the “Inside the Vault” tour gives visitors a look inside the Jamestown Rediscovery lab and the “Vault,” where the vast majority of Jamestown’s artifacts are stored. Conservators and curators will explain the processes they use to clean, stabilize, catalog, and store the artifacts found just feet away by the archaeological team. Learn more and buy tickets here.

At the Seawall just to the east of the Dale House Cafe, flotation continues in earnest. Curator Leah Stricker and Curatorial Intern Lindsay Bliss are using our repaired flotation tank to process the dozens of soil samples collected over the years from various features in and around James Fort. Flotation separates a heavy fraction (objects that sink) from the light fraction (objects that float) in order to more easily find artifacts (Watch a video describing this process). Leah and Lindsay’s primary goal is to find biological material such as charred wood, leaves, and seeds, all objects that tend to be in the light fraction. Flotation can take anywhere from about a half hour to several hours depending on the type of soil being processed. Denser soils such as clay require more time to disentegrate than loose, sandy soils. Visitors can watch flotation in action Tuesday through Thursday, weather permitting. One of the samples that Leah recently processed was from the 1608 ditch, very close to the ca. 1617 well. The heavy fraction contained burned daub and the light fraction contained charcoal, consistent with what the archaeologists were seeing while troweling through the feature. These are probably the remains of a nearby mud and stud building that met a fiery end.

In the lab, Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins is at work painstakingly mending pieces of a Bartmann jug. The jug has three medallions and during analysis of the collection’s Frechen stoneware, curator Leah Stricker found several sherds that she is confident — based on the glaze, the interior, the medallions, and the fabric — belong to the vessel. During his refit efforts Chris looks at both the exterior and interior of the vessel. The interior can be just as useful if not more so when looking for a piece that fits as the circular patterns from the throwing process are very prominent.

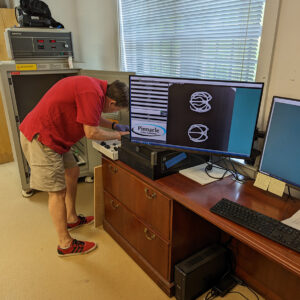

Intern Jackie Bucklew is working on creating a mount for the glass case bottle that she has been working on over the last several months. The case bottle is unusually large, easily the largest in the Jamestown collection. It will be mounted on its side and the mount will be created from 3M MicroBalloons, microscopic glass spheres that can be molded like putty and are not harmful to the 400-year-old bottle. Before the MicroBalloons are opened, a mold is created from Legos and then covered in plastic wrap. The MicroBalloons are then applied and molded to more perfectly fit the contours of the glass bottle. Also in the lab, Archaeological Conservator Don Warmke has been making up for lost time, creating record X-rays of many of the iron artifacts in the collection now that the X-ray machine is back up and running. Among his shots this month are sword parts, including hilts and pommels.

related images

- Excerpt from the Zuñiga Map showing James Fort and the “flag” feature extending from its north bulwark

- The archaeological team positions the protective well ring for lowering into the observation platform.

- Archaeologists Gabriel Brown, Josh Barber, and Caitlin Delmas at work on the well observation platform.

- Archaeologist Gabriel Brown builds the well observation platform.

- The team gives the final push for placement of the protective well ring into the observation platform.

- The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeology team slowly lowers the protective ring through the observation platform.

- Ceramic sherds and a pipe stem found in the north field excavations

- Archaeologists and visitors at the north field excavations

- Archaeologists Hannah Barch, Natalie Reid, and Anna Shackelford excavate one of the north field squares bit by bit.

- Some of the artifacts found in the north field dig. These objects span many different time periods of Jamestown’s history.

- Curator Leah Stricker holds pieces of daub found in the heavy fraction of a flotation sample from the 1608 ditch.

- Archaeological Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins pieces together a Bartmann Jug.

- Archaeological Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins shows the inside of the Bartmann jug he’s been mending. The circles from the jug’s throwing are easily discernible and are important clues during the mending process.

- Intern Jackie Bucklew displays the glass case bottle that she’s been mending over the last several months.

- Intern Jackie Bucklew hard at work building a mount for the glass case bottle.

- Archaeological Conservator Don Warmke prepares several sword pommels for an X-ray scan. His prior shot of two rapier hilts can be see on the screen.