It’s been an exciting month for the Jamestown Rediscovery team. Our archaeologists are now confident that the early ditch they’ve been excavating is part of the “flag” in the Zuñiga map of 1608. Long thought to simply be a flag on the map, it instead appears to represent this ditch and a possible enclosure at its northern end. Tracing the path of the ditch has led to the discovery of an early brick-lined well, likely dating to the late 1610s or early 1620s, right where the moat of Confederate Fort Pocahontas was constructed in 1861. Over near the Memorial Church, work has continued in earnest on an early pit feature, probably from the earliest years of the fort. An interesting mud and stud structure found a few feet away appears to possibly connect with the eastern palisade wall. Just to the west of the Church Tower a section of plaster from the collapse of the belfry during Bacon’s Rebellion has been excavated and brought to the lab for conservation and research. The archaeological team is busily preparing for burial excavations scheduled for next month in two different locations at Jamestown. The conservation and curatorial teams worked with Sarah Steele, a jet expert from the U.K., to differentiate between artifacts that are truly made from the gemstone and others that are simply jet-like. In preparation for presentations at January’s Society for Historical Archaeology conference in Portugal, our curatorial team is cross-mending and analyzing our collection of Portuguese Faience and Portuguese Coarseware. Lindsay Bliss, an intern from William & Mary, is using archaeological flotation techniques to recover floral and faunal remains from soil samples excavated from the fort’s second well.

The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists are confident that the early 17th-century ditch they’ve been following proves that the “flag” in the Zuñiga map of 1608 is not symbolic, but is a direct depiction of the very ditch they’re excavating, which marks out a large enclosure. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) surveys in 2019 provided the first indications of the presence of the ditch and enclosure and excavations have borne out the surveys’ findings. The idea of the “flag” as a feature rather than a flag was first put forth by former Senior Curator Bly Straube over a decade ago. Following the ditch south the team has run straight into the moat of Confederate Fort Pocahontas, built by enslaved labor under the direction of Confederate authorities to defend against Union ships in the James River. While excavating the moat, Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid discovered a series of bricks, unusual because the moat has been largely devoid of artifacts. As Natalie carefully removed more earth, a circular course of bricks was revealed, the telltale form of a well. The team believes they are only about four feet from the bottom of the well, the majority of the structure having been removed during the moat’s construction in 1861. The builder’s trench — the space surrounding the well created to allow the bricklayers to do their work — is about twelve feet in diameter and the well itself is about four. Wells are interesting archaeologically both as features and also because the colonists often used them as trash pits once they outlived their usefulness. This means they can be a treasure trove of artifacts. Additionally, organic materials such as leather, wood, seeds and the like can be preserved if they’ve spent the last four centuries below the water line where most organics-eating bacteria can’t reach them. Currently only half of the well’s circle has been exposed. The plan is to excavate the other side of the well down to the level of the current square so that the entirety of its diameter and builder’s trench are exposed before going any deeper.

To the west of the Church Tower the plaster of the collapsed wood-framed belfry has been removed and sent to the lab. Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Senior Conservator Dan Gamble worked together to gently remove the plaster along with several inches of soil beneath it so the more delicate work of separating the two can take place indoors. Nathaniel Bacon and his men burned the church tower and much of the rest of Jamestown on September 19, 1676, causing the belfry to collapse. This dates the plaster to a particular day, a rarity for objects in the Jamestown collection. The team is eager to see if the plaster matches that of the plaster found inside the church during prior excavations. That would give further evidence that this is indeed plaster from the church. Soil near the plaster has been scorched black by fire, and other portions of the soil were so affected by fire that they were baked to a brick-like color.

A few yards away, just north of the Church Tower, excavations continue in squares cut through by James Fort‘s palisade wall. The dig has finally resumed on an early pit feature that yielded brigandine armor and native ceramics in 2021. Two iron tools — somewhat resembling a modern hammer — have been found in the pit recently along with more pieces of brigandine armor. More artifacts from the pit will undoubtedly surface in the coming weeks. A matchlock lock mechanism — the ignition device in early muskets — was also excavated from the same unit this month. This object, though heavily corroded, is recognizable and is currently being conserved in the lab. It is the latest of dozens of such artifacts in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection, several of which are on display in the Archaearium. The eastern palisade wall goes right through this square. Only one of the post molds — the stain left by the wall posts as they slowly rot in the ground — is currently visible but the hope is that more of them will show up as the excavations go deeper. This section of the wall was not here long, since it was removed in 1608 as the fort expanded to a five-sided shape. This shorter period in the ground (less time to rot) may help explain the difficulty seeing the posts here compared to other sections of the wall where they are more easily discernable. A very interesting mud and stud building at the southern edge of the square may be a watchtower or guardhouse. Originally thought to be an early standalone building, the palisade wall here seems to connect to this structure that protrudes to the east a few feet from the palisade. The ball-like object mentioned in last month’s dig update is still sitting at the surface of a second pit feature here, and is still unidentified. Archaeologists have completed the backfilling of the northernmost square of these excavations after completing its excavation.

Down the hill to the north preparations continue for the excavation of a burial there. Found by archaeologists in the 1940s, the burial is dangerously close to a branch of the Pitch and Tar Swamp. The archaeological team is hoping that the burial is not below the water table, which could mean advanced deterioration of the bones. The team is excavating three adjacent squares down to the level of the current one to get a clearer picture of the burial and its contemporary surroundings. These squares were once the site of a modern road, so the top layers of gravel and fill that formed its roadbed were removed by a backhoe. We are interested in seeing what condition the remains are in, as this area floods fairly often, even if the burial is usually above the water table. Also, where there is one burial there tend to be more, so further GPR surveys and excavations are needed to see if this may be one grave of many. But the condition of the remains will inform the team’s decision whether to excavate any other burials so close to the swamp.

Other burials inside James Fort are also being prepared for excavation. An area near the southwest corner of the fort, originally excavated in 2005, yielded dozens of graves, only a few of which (including one thought to contain the remains of Richard Mutton) were excavated. GPR will be used to get a clearer picture of the burials before excavations proceed. Donning tyvek suits to prevent contamination of the remains with the archaeologists’ DNA and protected from the elements by a special shelter built by the archaeologists, the remains will be excavated next month. Scientific analysis will be conducted to see if there are familial ties between some of the colonists, learn about their diets, and attempt to identify some of them via genetic testing. Some bones have surfaced during excavations of the overburden but they were not human.

The conservation and curatorial staff have been happy to have Sarah Steele, an jet expert from Whitby, England, on-site to help differentiate Jamestown’s collection of jet and jet-like objects. Jet is a jemstone formed from ancient wood that has been exposed to extreme pressure over millions of years. Whitby is one of the two sites put forward as a candidate for the place of origin for our collection of jet crucifixes, the other being the Asturias region of Spain. Two of the crucifixes in the Jamestown collection have a style that is nearly identical to those in Whitby. Another two are very similar to those found there. Ms. Steele trained our staff on the techniques necessary to identify jet found in future excavations. She is working with Dr. Richard Hark of Yale University on research to pinpoint the geographic origin of jet objects based on their chemical properties. We are earmarking some of our jet artifacts to undergo pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry testing for isotopic analysis that will hopefully pinpoint our artifacts’ region of origin. Our conservation staff also worked with researchers at Colonial Williamsburg to identify the white substance used to highlight Christ and the cross on our jet crucifixes. X-ray fluorescence testing done there identified the substance as lead carbonate.

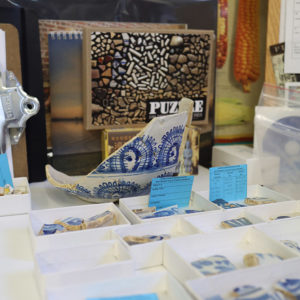

The curatorial team is busy cross-mending and analyzing the Jamestown collection of Portuguese Faience, a style of ceramic that imitated the style of Spanish ceramics, and then later, Chinese porcelain. Typically white with blue and sometimes purple decorative motifs, Portuguese Faience was first created in the 1550s and appears in Virginia for the first time in the 1630s. In an effort to prepare a presentation for the Society of Historical Archaeology (SHA) conference in Lisbon, all sherds of the ceramic have been gathered together for analysis. We now can identify at least 11 distinct vessels in the collection instead of eight prior to the effort. What’s more, the curators have been able to find new mends for existing vessels in an effort not unlike piecing together a puzzle. Most of the sherds belong to plates, though we have some bowls, cups, and a divided box as well.

Another type of ceramic being prepared for the SHA conference is Portuguese Coarseware. This orange, typically unglazed pottery first shows up in Jamestown contexts from the late 1610s or early 1620s. Our collection contains a jug, a bowl, and an olive jar as well as sherds of additional less complete vessels. A nearly complete pitcher, mended together from 166 sherds, is on exhibit in the Archaearium in a recreation of the well it was found in.

The team is excited to be working with intern Lindsay Bliss, a student from William & Mary, to recover botanical and faunal remains from soil found in James Fort’s second well. The flotation procedure she is using separates less dense plant and animal remains (which float to the top) from heavy material that sinks to the bottom. We are especially interested in gathering all of the faunal material together at this time as we’ve contracted with zooarchaeologists to identify the animal remains in the second well, informing us on the changing diets of the colonists as they recovered from the Starving Time winter of 1609-1610 and the food economy stabilized during the Martial Law period. Like other wells at Jamestown, the second well was used as a trash pit once it ceased being useful as a water source.

related images

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid shortly after discovering the well inside the Confederate moat.

- The church belfry plaster excavated west of the Church Tower

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford scores features at the north Church Tower excavations. Scoring makes it easier to see the sometimes-subtle boundaries between features and the surrounding soil.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford describes the north Church Tower excavations to visitors.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford excavates a pit inside one of the squares at the north Church Tower dig.

- Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin and Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford examine the matchlock lock found at the north Church Tower dig.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford shares the just-excavated matchlock lock with visitors.

- The matchlock lock found in the north Church Tower excavations.

- Some of the matchlock parts in Jamestown Rediscovery’s dry room.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Senior Conservator Dan Gamble excavate brigandine armor found at the north Church Tower excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Senior Conservator Dan Gamble place brigandine armor in a screen for transport to the lab.

- A piece of brigandine armor found in the north Church Tower excavations

- Brigandine armor pieces found during the north Church Tower excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas points to a sherd of ceramic found in the north Church Tower excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas holds a ceramic sherd found in the north Church Tower excavations.

- An iron tool found in the north Church Tower excavations

- Archaeologists filling in one of the squares at the north Church Tower dig site after the completion of excavations there.

- The archaeological team removes the fill from the earlier excavations in preparation for excavations at the 1607 burial ground.

- Jet expert Sarah Steele examines one of the jet crucifixes in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection.

- Portions of Jamestown Rediscovery’s Portuguese Faience collection.

- Portions of Jamestown Rediscovery’s Portuguese Faience collection.

- Partial Portuguese Faience vessels in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection.

- A Portuguese Faience vessel bearing the Portuguese coat of arms.

- A Portuguese Coarseware olive jar

- Portuguese Coarseware olive jar

- A Portuguese Coarseware púcaro

- A Portuguese Coarseware vessel

- Partial Portuguese Coarseware (orange and green at top-right) vessels in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection.

- The light fraction of organic material from James Fort’s second well after the flotation process. The light fraction is collected after floating to the surface.

- Curator Leah Stricker examines the heavy portion of a flotation sample from the Fort’s second well. The heavy portion of organics sinks to the bottom during flotation.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley gives a tour of the archaeological excavations inside James Fort.