November was a month full of long days and arduous excavation. The month began with the construction of protective structures over burial sites on the northern side of the 1907 Memorial Church and in the middle aisle of the 1608 Church. These structures were intended to protect the delicate excavations from the weather and prevent modern DNA contamination of the skeletal remains while exposed.

The crew first conducted excavations of the unit on the north side of the Memorial Church back in August 2018 in order to examine the 1640s church foundation. Here, they uncovered the intersection of two phases of brick church construction indicated by two different mortar types. While excavating this test unit, the team also found the outline of an early burial. Previous excavations nearby in 2016 had discovered very few graves here—suggesting that the colonists may have followed 17th century practices of using the north yard of churches as a place to inter social outcasts. Those previously uncovered graves shafts contained lots of brick bits and mortar fragments in their fill, indicating that they post-dated the construction of the brick church. By comparison, the lack of artifacts in the new grave’s fill gave hope that it might relate to the period in which the earlier 1617 timber-frame church served the parish.

Characteristic of Christian burials of this period, the burial was oriented east-west, and its shape was consistent with previously excavated graves, which contained hexagonal coffins. The fill content combined with the possible presence of a coffin piqued the archaeologists’ interest in excavating this burial and identifying this high status individual. Following the protocol developed for recent Jamestown burial projects, the archaeologists wore Tyvek suits, masks, and gloves during the excavation to prevent contamination of the remains’ surviving ancient DNA.

Archaeologists quickly removed the burial fill—stopping centimeters above the remains—and utilized ground penetrating radar (GPR) in an effort to collect data about what they would encounter. The GPR prospecting showed the absence of coffin hardware or nails, indicating that despite the burial’s initial shape, there was no coffin. Subsequent excavation proved this assertion. The remains of this individual were very well preserved and surprisingly intact. Following the excavation, Smithsonian forensic anthropologists Dr. Doug Owsley and Kari Bruwelheide visited Jamestown to examine the burials and conduct a preliminary analysis. Due to the level of preservation of the skeleton, the Smithsonian team should be able to learn quite a bit about the life of this individual. After a few long and careful days of excavation, the remains were removed to the lab for cleaning and study. Research on this individual’s remains continues.

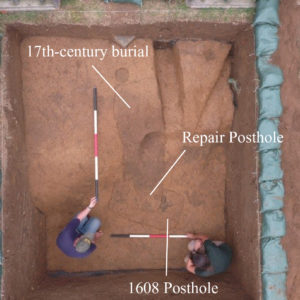

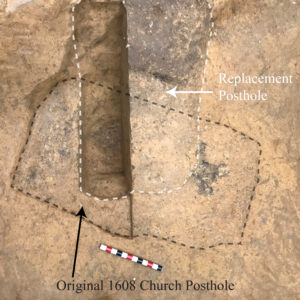

The burial in the 1608 Church was discovered during previous excavations in 2010, but was left unexcavated. However, due to the importance of the individuals buried in the 1617 church’s central aisle, the team decided to revisit the burial in the central aisle of the 1608 church, believing it may be Lord De La Warr. This burial was known to be cut by the Civil War Fort Pocahontas earthworks, a 20th-century utility line and box, and a posthole. Only a small portion of the burial remained, and, according to GPR data, it was the lower portion of the individual. Once uncovered, it became apparent that the individual was buried in a coffin, as seen by the presence of coffin nails and coffin stain. It also became clear that the burial had been re-excavated sometime in the 1600s, with most of the bones removed. The bones left in place included the feet and a portion of both fibulae. The fibulae were chopped through, suggesting that missing remains were removed with a shovel or similar implement. The removal of the remains in the 1600s was likely spurred by historic repairs done to the 1608 church. The burial had originally abutted a post supporting the roof of the church. At some point in the 1600s, this post needed to be replaced, and the new post was set to go through the burial. It is likely that the colonists dug up the burial when they put in the new post, in order to protect the remains. What little remained for archaeologists was carefully removed and sent in to the lab.

The repair posthole was likely created sometime prior to 1618, the year Lord De La Warr died and was buried at Jamestown. As a result, the burial must date to before that year, ruling out the possibility that it could be Lord De La Warr. The search for his burial will continue.

In late November, archaeologists returned to a previously uncovered feature adjacent to the cellar kitchen site within James Fort. This feature is a shallow, circular pit that contains heavy amounts of brick, clay, and burnt oyster shells. The presence of the burned oyster shells originally suggested that the pit was used for the production of lime for mortar. However, the results of our excavations indicate that this may not be the case, and research is still ongoing to understand the function of the feature. The completion of this excavation will allow for the team to partially backfill the area around the cellar kitchen.

The Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation and its board members held a ceremony in the beginning of November placing a time capsule in the Memorial Church chancel. This time capsule was placed at approximately the same location that one was found during the 2018 excavations inside the Memorial Church. The previous time capsule was buried during earlier an archaeological investigation done by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities between 1893 and 1906.

The month of November was also American Indian month. Daniel Firehawk Abbot from the Nanticoke tribe visited the first Saturday of November to interpret and spoke of Native American history and practices.

- Anna Shackelford beginning excavation of the burial on the north side of the Memorial Church

- Anna Shackelford cleaning the partially excavated burial

- Director of Archaeology David Givens scanning the burial with one of our GPR devices

- Michael Lavin and Alexis Ohman examining the fill in the burial shaft

- Constructing a clean room on the north side of the Memorial Church (Part 1)

- Ryan Krank hard at work building the clean room on the north side of the Memorial Church

- Constructing a clean room on the north side of the Memorial Church (Part 2)

- Anna Shackelford and Nicole Roenicke mapping the burial

- Nicole Roenicke talks with Dave Givens before helping to excavate the north burial

- One day ends…

- …Another begins

- Lesley Jennings monitoring the removal of backfill from within the 1608 church

- The burial and post holes in the 1608 church as they first appeared

- The two postholes found in the center of the 1608 church

- Building the clean room for the 1608 church

- Lesley Jennings and Ryan Krank cleaning off the large, rounded feature near the Kitchen Cellar

- The new time capsule