The Jamestown Rediscovery team was hard at work in December, tackling a variety of projects. The first task for the archaeological team was to finish the excavations in and around James Fort. Last month, the staff excavated two burials: one in the center aisle of the 1608 church, and the other on the north side of the Memorial Church. While the excavation of the skeletal remains from both locations was complete, the archaeological work was not quite finished.

In the 1608 church, there were two postholes left to excavate. One of these postholes had been for an original center post for the church, and had been cut into by the burial. However, a significant portion of the posthole survived despite the disturbance. The second posthole was part of 17th-century repairs to the church, and held a post intended to replace the original center post. The repair posthole not only cut into the burial, but also cut into the original center posthole. The latter feature contained almost no artifacts, but its size, shape, and construction methods have helped inform our understanding of the 1608 church.

During excavations into the repair posthole, the Rediscovery team recovered additional skeletal remains—all of which had originally come from the adjacent burial. Among the finds were two molars, which could provide the team with DNA samples for whoever had been interred in the burial.

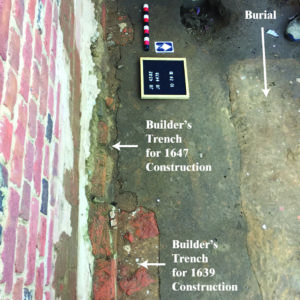

In the excavation area north of the Memorial Church, the team was able to excavate the builder’s trenches for the construction of the mid-17th-century brick church. That structure was begun in 1639 and completed sometime around 1647. The goal of the builder’s trench excavations was to expose the foundations for the brick church. The builder’s trenches were actually removed in November, but this month the team was able to perform additional analysis on the structural remains.

The foundations show clear evidence of two different construction periods: the first period (beginning in 1639) has a brick foundation with a stepped footer. The bricks used in that part of the foundation are of a uniform size, shape and color, and are bonded with a hard, grey, shell mortar. In stark contrast is the brick foundation for the second period of construction (ca. 1647). That brickwork is irregularly laid, with no clear bond pattern and no stepped footer. The bricks are a mix of normal and over-fired bricks (appearing purple in color) and the shell mortar used between the bricks is extremely soft and sandy—the sand content is presumably the source of the brown color of the mortar. This is exactly what the archaeological team expected to find, and reinforces the interpretation that the 17th-century brick church was built in two phases. The archaeological team is working on another portion of the brick church foundations on the south side of the Memorial Church as well.

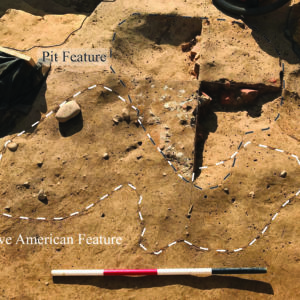

In November, Rediscovery also began excavating a large pit feature near the cellar kitchen within James Fort. This month, the team finished their excavation of the pit, after having removed two quarters of the feature. The exact purpose of this feature is not yet clear, but the team will be hard at work analyzing our finds during the next few months.

All around the pit feature were several other features of interest. These included small postholes—possibly for a fence line—very faint Native American features that undoubtedly predate the establishment of Jamestown in 1607. As with all new features, the archaeological team thoroughly mapped and photographed these finds.

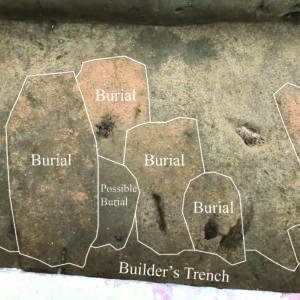

During the summer, then-interns Nicole Roenicke and Meaghan Harrington (now full-time staff archaeologists) began working on an excavation area east of the Memorial Church and churchyard. The duo uncovered evidence of a large number of burials in that space, and this month the archaeological team was able to return to that excavation area. The burials were mapped and photographed so that the units could be backfilled to protect the archaeological remains.

This month’s video features Cathrine Davis, who completed an externship in the Rediscovery lab this fall. Davis is a PhD student at the College of William & Mary and her proposed dissertation research focuses on consumption of French goods in North America—specifically French textiles via analysis of 17th-and 18th-century lead cloth seals. While working with the Rediscovery team, Davis photographed every single lead seal, and is creating a typology which will capture information about the shape and size of the seals, and what the different marks represent. This will serve as the basis for the Jamestown’s lead seal reference collection. Check out the video above for more info!

The team also helped with the installation of new signs in and around James Fort, replacing many of the older signs from around the site. The new interpretive signs contain updated information about the history of Jamestown and the archaeological investigations.

Beyond archaeology, the Rediscovery Education team hosted “At Christmas Be Mery,” an interpretive event set in 1618. Actors portraying historical figures—such as Sir George Yeardley—conducted holiday celebrations, singing hymns in the Memorial Church and ceremoniously burning sprigs of holly.

2019 has been an amazing, productive, and informative year for the Jamestown Rediscovery team. With the holidays—and cold weather—finally upon us, our archaeological staff is retreating indoors to plan out our excavations and projects for 2020. We hope that we will see all of you at Jamestown again in the new year. After all, you—our visitors, donors, and followers—make our work possible. From everyone here at Jamestown, thank you, and Happy New Year!

related images

- The builder’s trenches for the 17th-century brick church

- The foundation for the 17th-century brick church. The left section was built in 1639, and used a grey mortar. The right section was built in 1647, using a brown mortar

- The 1639 portion of the brick foundation

- The 1647 portion of the brick foundation

- The large pit feature turned out to be quite shallow, and surprisingly fully of brick

- A view of the bricks and clay found in the large pit feature, which was relatively shallow

- A Native American feature that predates Jamestown was found immediately north of the large pit feature

- A view of the many features uncovered east of the Memorial Church and churchyard

- A close up view of some of the burials found east of the Memorial Church. The builder’s trench is for the church yard wall

- This photo shows the bottom of the burial, repair posthole, and center posthole found in the 1608 church

- Standing guard at the bonfire during ‘At Christmas Be Mery’

- Making an offering during ‘At Christmas Be Mery’

- A ghostly visage in the Memorial Church from ‘At Christmas Be Mery’