This February, new discoveries in the Memorial Church boosted the Jamestown Rediscovery team’s optimism that more evidence of the third, fourth, and fifth churches on the site survives than they previously thought. As the team has peeled back early-20th-century work, they have revealed what those Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquites preservationists encountered. Despite reports about the extensive excavations around the church ruins, evidence for at least two church floors survive in part and appear fairly untouched since the late 17th to early 18th century. In addition to these findings, the test at the northeast corner of the Jamestown church tower exposed an unexpected architectural element in the 1640s church’s west wall foundation.

First, the team expanded the chancel excavation west and focused on a raised line of brickwork that was reestablished by the APVA in 1905, when the chancel was reconstructed, to demarcate what the early excavators had encountered during their digging. This slightly raised brick curb served as a division between the chancel and cross aisle for the most recent church, rebuilt in the 1680s after Bacon’s Rebellion. The cross aisle was a brick walkway, oriented north-south, right in front of the south door for the 17th-century brick churches. Because the 1907 reconstructed Memorial Church design was based on St. Luke’s Church in Smithfield, VA, the south door was moved closer to the tower to match St. Luke’s entrance. Also, the APVA moved the door because they did not want visitors walking on the two ledger stones paving the cross aisle’s south side. Look for more about those ledger stones in next month’s update!

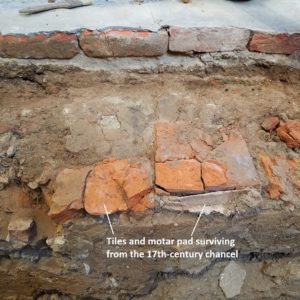

Concrete capped the entire 1907 division wall between the inner chance and the chancel aisle, but when removed it revealed a short wall of bricks, broken tiles, and 27 yellow bricks of unusual dimensions very similar to “Dutch bricks.” After removal of the modern brickwork, a thin lens of 20th-century backfill was removed, revealing the most exciting discovery—brick tiles and the mortar pad for an intact original chancel floor survived! Hopefully, by careful excavation of the tiles and mortar pad the crew can determine the date for the floor in the coming weeks.

The team is eager to see how far the intact floor remnants found in the body of the church in January extend to the west. Along with the mortar pad and a few frail bricks left in situ, they noted that a significant amount of brick scatter lies beneath the mortar. Perhaps these were low-fired bricks of an earlier floor or maybe they were laid to help level the surface before the mortar pad was placed. Curiously, the mortar pad and few remaining bricks in situ came to an abrupt end approximately 16′ east of the 1640s church’s east wall. Could this break delineate western limits for the 1640s church chancel and possibly its 1617 predecessor?

If the break in the floor does mark the 1640s chancel, and if it matches the location of the earlier 1617 chancel, it would also precisely define the location of a most significant event in this nation’s history. This would mark the spot where the first General Assembly met in July 1619. According the General Assembly clerk John Twine, “…all the Burgesses took their places in the quire [choir] till a prayer was said by Mr. Buck, the minister.” The quire or choir is often part of or the same as the chancel. Stay tuned!

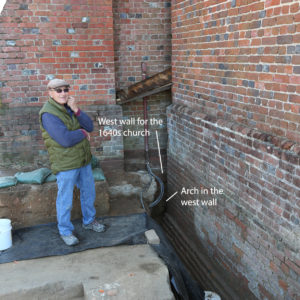

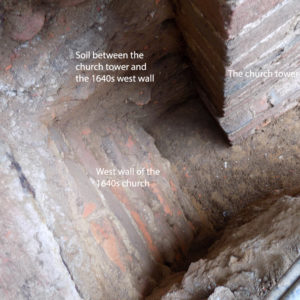

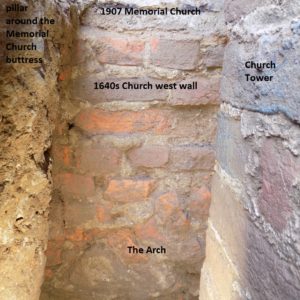

Finally, the team finished the test in the northeast corner of the old church tower revealing a possible tower builder’s trench and the absence of a spread footing along the towers east side. However, the real surprise is what the test exposed in the 1640s foundation. The top 1′-2′ of the foundation was identical to the north, south, and east walls. Similar to the other three walls, the underground brickwork is untidy because the colonial masons stood directly on the brickwork as they built the wall up out of the builder’s trench. They were unconcerned with the mortar oozing outside of wall form, as it would be hidden from view.

Despite the sloppy workmanship and numerous recycled bricks used in the wall, English bond was obvious. However, when the bottom foot of the wall was revealed, it seemed to have no bonding at all. Initially, it appeared as though the masons filled the bottom foot of their builder’s trench with brick rubble and mortar all mashed into the builder’s trench with no recognizable form—and then they constructed more consistent bonding on this rubble-mortar mixture. However, Master Brick Mason Ray Canetti visited the site during the excavation and remarked that it looked like the beginning of the north half of an arch. Further cleaning of the mortar coating the uneven brickwork confirmed Canetti’s evaluation. The presence of this feature is puzzling, but perhaps it was a drain for leading rain water away from the church foundations.

Check out the video update on our Jamestown Rediscovery YouTube channel for a summary of this month’s work!

related images

- Chancel, aisle, Rev. John Clough stone, and Knight’s Tombstone within the Memorial Church

- Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley removes concrete from the top of a division between the chancel and cross aisle. It was placed here in 1905 to represent what early 20th-century excavators encountered. The wood in the division was part of a modern rail along the division.

- The division between the chancel and the cross aisle after the removal of the concrete cap.

- 17th-century tiles and mortar pad underneath the 1905 APVA brick and concrete layer

- Mortar pad and tiles partially in place but left unexcavated by the APVA in 1901-1902

- Tiles and mortar pad from the 17th-century church chancel

- Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley inspects the surviving tile floor in the chancel

- Dr. Bill Kelso, Bob Chartrand, and Danny Schmidt examine the mortar pad and few bricks in situ in the surviving church floor

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand removes 20th-century excavation backfill sealing a surviving section of church floor.

- Bob Chartrand and Amy Baker excavate in the Memorial Church

- Brickwork and mortar from the earlier church under the Memorial Church floor

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand points to the end of the surviving mortar pad in the body of the church. this may be the western limits to the 1640s church chancel and might have also been the limits to the 1617 church.

- Archaeologist Dave Givens maps some of the bricks in situ in the church floor.

- Master Mason Ray Canetti visits the church tower site during excavation

- Archaeologist Dave Givens examines the arch in the west wall of the 1640s church at the corner of the church tower.

- Looking straight down at the test at the northeast corner of the church tower

- The arch in the 1640s church west wall before the excess mortar was cleaned away.

- Arch and other features within the church wall

- A close-up view of the brick arch within the church wall