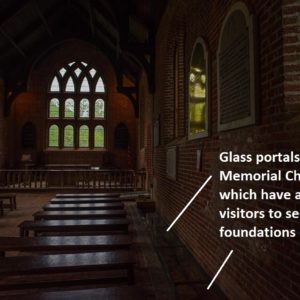

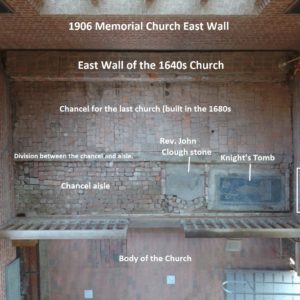

Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists continued excavations in the 1907 Memorial Church this March, focusing on the foundations of the 1617 church. For decades visitors have been able to look through glass portals in the floor to see the cobblestone foundations of Jamestown’s “third church.” It was here that the first General Assembly met on July 30, 1619. Referenced by the Ancient Planters in their Brief Declaration, this church was described as “of timber being fifty foot in length and twenty foot breadth.”

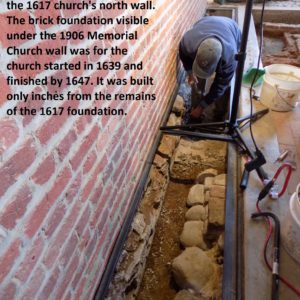

The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA) found the north and south foundations of the 1617 church during their excavations in 1901. They describe a cobblestone footing with a layer of bricks set on top that made the wall nine inches thick. Upon completion of their excavations, the APVA poured concrete in between surviving sections of wall, and then filled the narrow gap between this foundation and the 1640s brick foundation, which was built just outside. Archaeologists started by cleaning the north wall, which had three sections of wall separated by gaps of several feet. Convinced it was necessary to remove the concrete, archaeologists were confident evidence overlooked by the early 20th century excavators would be revealed. “We figured it was very likely that the APVA poured concrete into the areas where they found no cobblestones or bricks like those in the undamaged portions of the foundation. However, there was hope that some of the yellow clay, which secures those cobbles, might survive under the concrete,” explained, field supervisor Mary Anna Hartley.

Their assessment of the concrete’s placement was accurate. Not only did the concrete conceal intact clay related to the foundation, but it also hid the clues as to why the wall was so fragmented. The team identified the outlines of approximately six burial shafts along the wall’s interior that cut through the 1617 church’s north foundation. These graves, likely related to the 1640s church, had undercut and obliterated several feet of the 1617 wall. The removal of the first five feet of concrete revealed an additional four feet of the 1617 wall, which was indicated by intact yellow clay with impressions where cobblestone had once been placed.

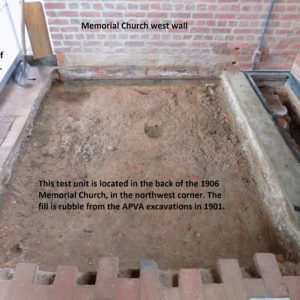

Simultaneously, while working on the 1617 foundations, archaeologists opened up a test unit in the back northwest corner of the church. The goal was to find evidence of the 1617 church’s west wall, as the location of the east and west ends had not been determined. Shown in 1901 photographs, excavations in that corner were deeper than in other parts of the church. Thus far, the unit is full of the APVA backfill and contains fragments of burned plaster, some nails, brick, and mortar. The only ceramics uncovered in the area were fragments of banded yellow ware and blue shell-edge white ware. Curator Merry Outlaw says, “the ceramics included sherds of a jug and a platter, both dating to about the mid-19th century and relating to food serving. Perhaps they are remnants of ceramic objects broken during picnics in the area, or they may relate to 1860s food consumption in the nearby Civil War fort. ”

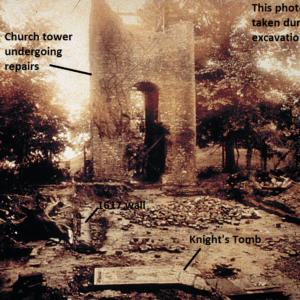

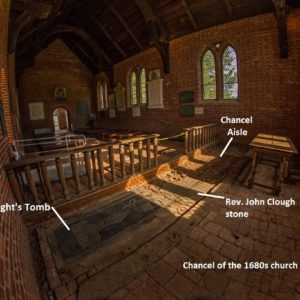

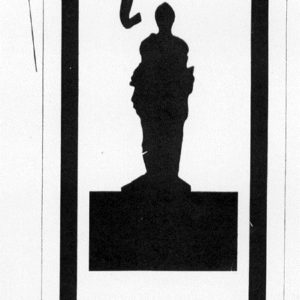

Finally, discussions began about the conservation of one of Jamestown’s most iconic artifacts–a ledger stone known as the “Knight’s Tombstone.” This rectangular black stone slab is approximately six feet long by three feet, and it bears carved depressions in which monumental brass plates were once attached . It is the only surviving ledger stone of its kind in this country.

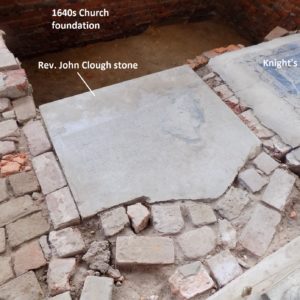

In 1901 this ledger stone, along with the fragment of another for Reverend John Clough, were found in the chancel aisle, just inside the south entrance of the church. They most likely relate to Jamestown’s last colonial church, which was built in the 1680s following the Bacon’s Rebellion fire that destroyed the 1640s church.

When the stone was uncovered in the early 20th century, the brasses were missing and it is unknown whose grave it originally marked. However, two knights were buried in the 1617 church on this site. The first, Thomas West, the Lord De La Warr, was buried at Jamestown after dying on the voyage over in 1618. The second, Sir George Yeardley, was buried here in 1627. Research into the ledger stone and to whom it belongs is ongoing.

Early 20th-century reports and photos illustrate that today the Knight’s Tombstone in approximately the same location where it was uncovered just over a hundred years ago. The APVA moved it only a foot to the south, placed it on a brick base, and then repaired the pre-existing breaks with Portland cement. John Tyler, Jr., an engineer who worked at Jamestown in May and June of 1901 (and also the grandson of President John Tyler) wrote this about the Knight’s Tombstone discovery:

“Immediately upon entering this door was found a tomb, lying north and south along the aisle. This tomb had been robbed of the brass tablets with which it had been inlaid. The stone, however, bears the channels in which the brass was, as well as the brass bolts, leaded in the stone. These bolts held the tablets, consisting of a rectangular border 2 inches wide, and enclosing in the northeast corner of the stone and a shield, and in the northwest a scroll, and down the middle of the tomb a knight in armor standing upon a rectangular plate which evidently bore the inscription.”

Jamestown Rediscovery archaeological conservators consulted with well-known Monuments Conservator Jonathan Appell about moving and conserving the stone. As noted by senior conservator Michael Lavin, “Monuments conservation is completely different from archaeological conservation. There are different methods, tools, and chemicals involved when working with stone.” Appell will begin working with the team on Phase I of the restoration of this significant artifact in April. In the meantime, the Reverend John Clough tombstone north of the Knight’s Tombstone was moved. Like the Knight’s Tombstone, the APVA had placed it upon a brick base. Both stones will be replaced in the chancel when excavations are completed.

Check out the video update on our Jamestown Rediscovery YouTube channel for a behind-the-scenes update from our lab!

related images

- Glass portals in the Memorial Church

- 1617 and 1640s church foundations

- Down in the trench dug by the APVA excavators to expose the 1617 church foundation. Concrete was poured over areas where cobblestones were missing, in between sections of the wall. A thin layer of dirt was put over the concrete. The black frame above the trench held the glass through which the foundations were viewed by visitors for many decades.

- Looking at the middle section of cobblestone foundation related to the timber-frame church built in 1617. The APVA poured 2-3 inches of concrete in the areas where they found no evidence of the wall.

- Amy Baker removes concrete in between sections of cobblestone foundation for the 1617 church’s north wall. The brick foundation visible under the 1907 Memorial Church wall was for the church started in 1639 and finished by 1647. It was built only inches from the remains of the 1617 foundation.

- A Native American stone scraper with shell mortar attached was found in the APVA rubble around the 1617 foundations

- 1617 and 1640s foundations and features

- 1617 and 1640s church foundations

- Test unit in the northwest corner of the Memorial Church

- Bob Chartrand cleans the APVA rubble layer in the unit located in the back corner of the church

- Whiteware and Yellow ware found in the Memorial Church

- Mary Anna Hartley excavates the APVA rubble in the back corner of the church

- This photo was taken during APVA excavations in 1901.

- Features of Jamestown’s many churches

- Tombstones within the church chancel

- The Knight’s Tombstone within the Memorial Church

- Illustration of the inlay on the Knight’s Tombstone

- Rev. John Clough stone and the Knight’s Tombstone

- Preparing to move the Rev. John Clough tombstone

- Jamestown Rediscovery staff moving the Rev. John Clough stone