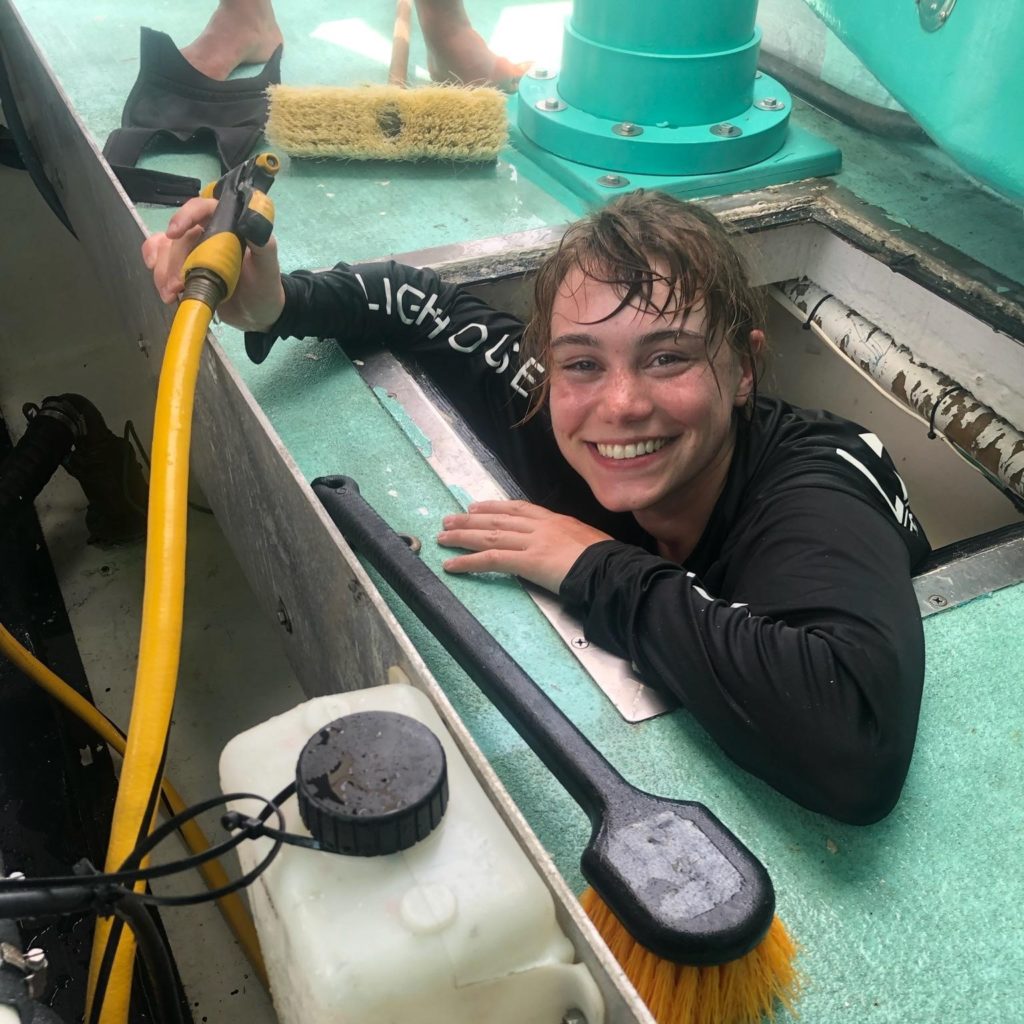

When it’s my turn to give the 11am Archaeology tour, I usually start off by telling people about my background and how I got started in fieldwork. I mention how in the summer of 2019, I traveled from my hometown of Williamsburg, Virginia to St. Augustine, Florida to participate in the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP) field school. As the name indicates, this was a maritime archaeology field school, where excavation meant donning SCUBA gear and using my hands to scoop silty mud into a dredge to uncover evidence of a shipwreck. Here at Jamestown, excavation means using a wide range of tools—from jackhammers to dental picks—to uncover the incredibly well-preserved features and artifacts from the 17th century. Whilst my experience excavating was very different once I started working on land, there were similarities between the sites that interested me. Not only are St. Augustine and Jamestown very early colonial sites, both LAMP and Jamestown are also invested in doing public archaeology.

When a site is committed to doing public archaeology, it means that the communication of what you’re finding to the general public is of the utmost importance to the project. This is exceedingly rare in the U.S. and around the world. Most archaeological sites aren’t open to the public and most reports about what was found on a site only appear in academic journals. At a public archaeology site like Jamestown, we can publish papers in academic journals and share what was just pulled out of the ground with a visitor that happens to walk by at that moment. My interest in public archaeology is what led me from St. Augustine to Jamestown, and I am now in charge of yet another feature to Jamestown’s commitment to public archaeology: the Ed Shed.

The Ed Shed is a children’s educational space, designed to provide a different experience than the excavations and the museum. Instead of only being able to see an artifact at the excavation areas or in a museum display, visitors to the Ed Shed will be able to touch and sort real artifacts, use geographic technology to map archaeological features, and more. Public archaeology is ultimately about expanding what people think of archaeology and its relevancy to their lives. To me, the Ed Shed’s activities help fulfill the public archaeology mission in a different way. As a child, I always preferred learning by doing rather than seeing or reading. That’s part of the reason I love fieldwork so much, whether it’s digging or diving. Our excavation sites are big logic puzzles—who did what, where, at which time? Except instead of existing only on a piece of paper, the puzzle is the physical layers of dirt and the artifacts in front of you.

I’m so happy to be able to create a space where a younger me would have been able to understand how pottery was made 400 years ago by feeling a fingerprint left in the clay by a 17th-century potter, or making my own map of the dig site instead of just being shown one. It is my sincerest hope that kids who visit Jamestown this summer will go back to school, see archaeology mentioned in a textbook somewhere, and excitedly remember the time they actually got to do archaeology at the Ed Shed.

– Natalie Reid, Staff Archaeologist and Ed Shed Manager.

Related Images

- Natalie shows two young visitors a fragment of a ceramic.

- A visitor closely examines a tiny artifact to sort it into the correct category.

- The Ed Shed is open in the summer and for special events.