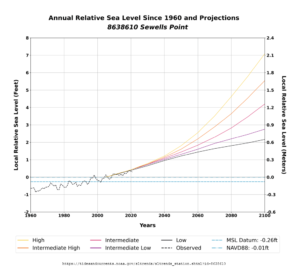

Sea level rise is affecting Jamestown Island both on its shoreline and via the encroachment of a branch of the Pitch and Tar Swamp that cuts through it. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has named Jamestown one of 2022’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places because of the problems sea level rise is causing on the island now and the threats it poses for the future. Work will soon begin on a new footing for the seawall to prevent it sinking further into the river. Barges sit close to the shoreline with the tools and supplies needed to ensure the seawall is prepared to protect the island and its cultural resources for decades to come. Land near the Rediscovery Center that was once dry enough to be mowed and excavated is now swampland. A buoy downriver in Norfolk (Sewell’s Point) has recorded that the water level there has risen almost 1.5 feet since 1930. Projections by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predict that by 2100 the level will rise an additional 2 to 7 feet, making the 3-foot floods that currently happen 5 or 6 times a year a preview of the future’s everyday level. Future flooding on top of that would be catastrophic. The Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation is committed to preserving Jamestown and its priceless historic and archaeological resources. To learn more about the challenges facing Jamestown due to sea level rise, please visit https://historicjamestowne.org/savejamestown/.

The 2022 dig season is now in full swing and the excavations continue on the west and north sides of the 1680s church tower. Just to the west of the entrance of the tower the archaeological team is finishing up their work in preparation for backfilling the excavations there. This site contained evidence for the burning and collapse of the 1617 church belfry at the hands of Nathaniel Bacon and his followers during Bacon’s Rebellion. A few feet to the north the team continues to excavate two squares, one of which has yielded fort-period postholes and the other contains fort-period planting furrows. In the lab, Archaeological Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins and Curator Leah Stricker are processing a number of leather and wooden artifacts that were pulled out of the fort’s second well in 2009. A number of shoes were found beneath the well’s surface, their waterlogged state enabling the rare survival of these and other leather objects from the early 1600s. All of this month’s activity was not solely at Jamestown. David Givens, Director of Archaeology for Jamestown Rediscovery, spent a week at Bermuda helping locate historic resources through the use of ground-penetrating radar (GPR). In King William, Virginia he and his team also used GPR to help identify unmarked burials on Upper Mattaponi tribal grounds. Out-of-context artifacts are being gathered by Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid for use in the Ed Shed, a building just outside James Fort where archaeological concepts are taught to young visitors. Assistant Curator Janene Johnston has created a primer for the arms and armor in the Jamestown collection that is being presented at the Fields of Conflict conference in Edinburgh, Scotland.

A few feet to the west of the church tower entrance work will soon switch from excavation to preservation as the archaeologists begin to backfill the area to preserve the archaeologically-exposed historic layers. The area was chosen to be excavated when the digging of a test pit revealed a burn layer. Over the past several months excavations revealed this burn layer to be evidence of Bacon’s Rebellion, namely Nathaniel Bacon and his followers’ burning of Jamestown on September 19, 1676. The dark layer is just under the construction debris of the church tower that was built just a few years later. The building of the tower was necessitated by the torching of the timber-frame belfry, a holdover from the construction of the 1617 church. When in 1639 the construction of the brick church began to replace the 1617 timber frame one, the belfry from the earlier church was left standing and was integrated into the brick church. But the destruction of the structure necessitated construction of a new belfry, one that still stands today. The burn layer is neatly contained; the team followed the bounds of the layer and while present in much of the first square it only slightly extended into two neighboring squares. It seems the belfry crashed down and continued to burn almost entirely into the initial excavation square.

There are two squares that the team is working on just north of the church. In the one closest to the church, postholes for an early mud-and-stud building have been found. The footprint closely resembles the Corps de Garde excavated earlier. The archaeological remains of a sill trench for the building have also been found, which is a rare occurrence at Jamestown. The sill trench is where the clay (“mud”) wall sat on the ground. Typically the postholes/postmolds of the support posts are found in an early building such as this but the rarer sill trench lends additional evidence to this being a mud-and-stud structure. While the fort’s palisade wall went through this square, little evidence of its existence is turning up. This may be due to the fact that the wall was only there for about a year. In 1608 this section of the fort’s wall was removed when the fort was expanded eastward to become a five-sided fort. It may be because the palisade logs here weren’t in the ground very long that there isn’t the telltale rot in the form of postmolds found elsewhere where the palisade once stood. Perhaps further excavations will reveal evidence of the palisade here in the weeks ahead. Just across the footpath, work is finishing up on the last square currently being dug. A series of very early planting furrows have been found here, dating to the first year of the fort (prior to the expansion in 1608) because they run parallel to the eastern palisade wall. A ditch found in the square probably marks the boundary of church property.

A large collection of faunal and botanical artifacts from James Fort’s second well were processed this month. Trapped underwater for 400 years, leather and wooden objects were preserved specifically because they weren’t exposed to the air above. The lack of exposure to the air prevented bacteria and other tiny organisms from reaching and consuming these objects. The second well was constructed in the extreme northern portion of the fort, probably in an effort to source water as far away from the brackish James River as possible while still within the fort’s palisade wall. The conservators at Colonial Williamsburg used a freeze-drying process to remove the moisture from these objects in order to make long-term preservation possible. Archaeological Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins and Curator Leah Stricker have cataloged and built custom storage for these objects, including shoes (both for adults and children), leather straps, scrap leather, casks, tankards, and handles. These are held in temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms where environment-monitoring hardware reports this data to the conservators. Fluctuations in humidity and temperature need to be avoided to ensure these objects’ longevity.

Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid is gathering artifacts for use in the Ed Shed, an on-site building where younger visitors and their families can learn about archaeological processes. These objects are all out of context — that is they can’t be tied to a specific archaeological feature, but have all been found on our site. An example of this would be when a visitor finds an artifact on the ground and brings it to a staff member. Because of this, they are less useful to our researchers but are perfect for teaching children archaeological concepts in the Ed Shed. Hundreds of pipe stems in our collection are out of context. But they are a valuable tool to teach folks the correlation between a stem’s bore diameter and its manufacture date. As tobacco became more abundant, the diameter of the pipe stem’s bore decreased while the bowl’s size increased. Through a number of studies and a sample size of thousands of stems, this correlation has been found to be accurate to within just a few years. These pipe stems and other objects such as wine bottle glass, beads, projectile points, and ceramics of both European and Native can be held and examined by visitors to the Ed Shed.

Members of the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeological team travelled to King William, Virginia to help members of the Upper Mattaponi tribe locate unmarked burials. Bringing their ground-penetrating radar (GPR), drone, and surveying equipment with them, surveys were conducted on three different sites to help the tribe preserve and protect gravesites in perpetuity.

Some 760 miles away in Bermuda, Jamestown Rediscovery’s Director of Archaeology David Givens worked with Dr. Michael Jarvis from the University of Rochester and Peter Leach of Geophysical Survey Systems to locate historic features — also using ground-penetrating radar (GPR). Surveys were conducted at three sites on Bermuda: King’s Square in St George’s, Smallpox Bay on Smith’s Island in St George’s Harbour, and Trunk Island in Harrington Sound. Working in partnership with the the Bermuda National Trust, the St. George’s Foundation, the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum, and Zoo, and the Corporation of St. George’s, this was the first archaeological use of GPR in Bermuda. The team has yet to thoroughly analyze the data but initial readings are promising and will likely lead to excavations in the summer. Doing a GPR survey first makes the research much less destructive…you can let the GPR device take the guesswork out of where to focus your excavations. This is especially helpful in an urban setting like St. George’s. You can read more about the work, with details on each site in Bermuda here and here.

Assistant Curator Janene Johnston has created a survey of Jamestown Rediscovery’s arms and armor collection for The University of Edinburgh’s 11th Biennial Fields of Conflict Conference. The document gives a high-level view of the range of artifacts in the collection, from swords, pikes, halberds, projectile points and pistols, to jack-of-plate, chain mail, and plate armor. A sizable portion of these artifacts can be seen in our Archaearium museum but those researchers wishing to work with our collection for their projects are encouraged to contact us.

related images