This month marks the anniversary of the March 1622 attack by Native peoples on the colony in Virginia. While James Fort was apparently warned and was not subject to the attack, the attempt has overshadowed the complicated relationship between the two peoples. Archaeology has revealed a more detailed narrative of Native and newcomer interacting and negotiating a complex cultural space. Excavations at Jamestown have uncovered a stunning and unparalleled look at Virginia Indian material culture at the inception of English colonization. In this year, the archaeology team will again explore the complex and entangled interactions between the groups. The discoveries in the North Church area described below are a microcosm of such interactions.

In remembrance of this solemn occasion, Jamestown Rediscovery held a commemoration in the Memorial Church. Dignitaries from Virginia Indian tribes, members of the Jamestowne Society (descendants of the early colonists), and our Historic Triangle colleagues attended the event. Speakers discussed the events of 1622 and the history of Native and English interactions, and presented a vision of a more truthful and inclusive history of Jamestown on which we can build a future.

As much as the inconstant weather of spring in Virginia allows, excavations are being conducted north of the Church Tower just outside the eastern palisade wall of James Fort. Archaeologists there are exploring two separate squares, one with a fort-period pit and the other with an early ditch that likely marked the boundary of the church’s property. Fragments of the “Knight’s Tombstone” are being returned to Jamestown after a study of it and other tombstones found in colonial Chesapeake contexts. The study used historical and geological evidence — including examination of fossils trapped in the limestone — to determine their origin. In the Jamestown Rediscovery Center conservators and curators are working on a number of interesting artifacts found in the field including sherds of a fuming pot, pipe fragments from the “Bookbinder” pipe maker, a book clasp, and a sword scabbard chape.

Two separate excavation areas, just feet apart north of the Church Tower, will be the immediate focus of the archaeologists this season. In the section closest to the church, Archaeologists will continue to excavate a fort-period pit found last year that yielded brigandine armor and Virginia Indian ceramics. This multicultural deposit may indicate a period when the colonists and local tribes were on good terms and were trading with one another. Jamestown was settled on land belonging to the local Paspahegh tribe and the colonists were attacked soon after landing. Periods of conflict and peace checkered the years between 1607 and 1622.

The second area, just a bit to the north, contains an early ditch and a layer of brick rubble. The rubble is most likely associated with the construction of the late 1640s church, one of the iterations of churches built on the same spot where the Memorial Church stands now. Roughly perpendicular to the line of brick, an earlier ditch, perhaps marking the boundary of church property, runs underneath the rubble. Where the two features meet the brick has settled a bit into the ditch. Two colors of soil are mottled together adjacent to the ditch, but the fill within the feature contains only one type of soil. This difference in content helps indicate the boundary of the ditch. Also prominent in this excavation square are a number of oyster shells, embedded in what appears to be a planting furrow from early James Fort-period farming activities. Complicating interpretations are disturbances from roots, which archaeologists often call “bioturbation.” The square is close to a large cedar tree that quickly drinks up the water archaeologists spray on the features use to help contrast them against the surrounding soil.

Later in the season the team plans to conduct further ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys in areas north of the fort. Preliminary runs have suggested that there are possible features there and secondary surveys and targeted excavations are planned in the months ahead. A branch of the Pitch and Tar Swamp is in this area but GPR surveys in some of the shallower portions of the swamp last month indicate that GPR can be effective in these wet environments as well.

Fragments of the “Knight’s Tombstone” have been returned to Jamestown. The fragments were loaned to the team of Marcus Key, Rebecca Rossi, and Robert Teagle as part of a larger study to identify the source for its limestone and that of several other similar tombstones in the Chesapeake area. The study examined the tombstones and fossils trapped in their limestone as well as the historical evidence to suggest these black limestone slabs came from Belgium by way of London. The “Knight’s Tombstone” is thought to belong to Sir George Yeardley, knighted by King James I prior to his departure for Virginia and twice governor of the colony. You can read the full study here: Historical Geoarchaeological Approach to Sourcing Seventeenth- to Eighteenth-Century Black “Marble” Ledger Stones From the Chesapeake Bay Region, U.S.A.

A number of interesting artifacts are being conserved and cataloged this month including an iron scabbard chape, a copper alloy book clasp, a copper alloy mount that would have attached to a leather object, and pipe fragments from the “Bookbinder” pipe maker found in the seawall excavations from last year. Also found in the seawall excavations were sherds from a fuming pot that mend with other fragments found in 1997.

Archaeological Conservator Don Warmke is in the process of conserving of a scabbard chape, an iron piece attached to the bottom of a sword’s scabbard. Found in James Fort’s kitchen, the chape is one of 84 found at James Fort over the years. Among the pieces Senior Archaeological Conservator Dan Gamble is working on this month are a book clasp and a mount, both made of copper alloy. The book clasp has a series of five stamps on it and was found in the plowzone. It is one of many pieces of book hardware in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection (this artifact is labeled Book Catch 114229). The mount would have been attached to a piece of leather, perhaps a belt. It was found south of the Church Tower.

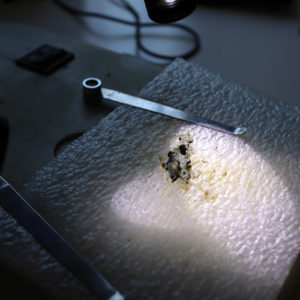

Sherds from a fuming pot, similar to today’s incense burners, were discovered while washing artifacts found in last summer’s Seawall excavations. These sherds mend with pieces found in excavations from 1997 that were conducted just a few feet away. Fuming pots were used to heat herbs or fragrant wood to disguise bad smells. Holes in the pot and an open top would allow the fragrance to waft out. The pot is the only example in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection and was made by potters working in the border region between Surrey and Hampshire, England.

Also found in the Seawall excavations are several fragments of tobacco pipes made by the “Bookbinder” pipe maker. So named because of a distinctive decorative imprint and marbleized design reminiscent of book covers, the Bookbinder’s pipes have been found on a number of seventeenth-century sites. Evidence points to their manufacture in the Virginia Beach area in the 1640s. For more information on seventeenth-century Cheseapeake pipes, including those made by the Bookbinder, read Seventeenth-Century Tobacco Pipe Manufacturing in the Chesapeake Region: A Preliminary Delineation of Makers and Their Styles.

The team is busily preparing for resumption of the Archaeological Field School, the first in several years. COVID-19 has prevented the school from occurring the past couple of years and the team is eager to lead this year’s group of students in field and lab instruction.