During January most of the archaeologists are focused on indoor tasks including report writing, digital mapping of features, and helping the collections staff with artifact processing. Director of Archaeology Sean Romo, and Senior Staff Archaeologists Mary Anna Hartley and Anna Shackelford have taken the time to plan this year’s excavations. At Smithfield, a low-lying area northwest of James Fort, the three have drawn up plans to dig 21 5′ x 5′ squares in a north/south line from the Archaearium museum to the Dale House Café. The hope here is to identify any burials or other features quickly (5′ x 5’s are 25% of the area of the usual 10′ x 10′ and thus should take much less time to excavate) as the area is increasingly flood prone and archaeological resources are being lost. Of particular interest to the team are burials. The burial excavated this year in Smithfield was in exceedingly poor shape, with very little bone surviving . . . the majority of what was left was stains in the soil. By excavating these squares the team hopes at the very least to learn the bounds of the graveyard here. Archaeological monitoring by the National Park Service in the first half of the 20th

century noted a burial just outside the Dale House Café. Could that be part of the same burial ground as is found where the Archaearium (and previously the 17th-century statehouse) now sits? The line of excavations should go a long way in informing the archaeologists what lies beneath Smithfield. They can then plan how best to approach the area and record those layers.

Near the eastern edge of Smithfield the plan is to continue the excavations of three 6′ x 6′ foundations discovered by ground-penetrating radar (GPR). There is thought that these might be Confederate artillery barracks and later served as shelters for escaped enslaved people once the Union forces captured the island. The team is basing these hypotheses on primary materials including a hand-drawn map of Jamestown Island during the Civil War, housed in William & Mary’s special collections library. The archaeologists have had difficulty ground-proofing these hypotheses because the area is often too saturated to conduct excavations. The dig here will be resumed as soon as it’s dry enough to do so.

Just outside the Godspeed Cottage, former home of Dr. William Kelso and now office space for the archaeological team, Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown is leading excavations in an area that contained a high amplitude target per a GPR survey. Yet surprisingly, the dig here has yet to turn up anything of note. The team has opened up a 10′ x 10′ and an additional 5′ x 10′ in the search for the feature that showed up so prominently on GPR. The excavations are about a foot and a half deep at this point and Gabriel is planning another GPR survey here now that the excavations are substantially below the surface. In the early 20th century, this area was planted with fruit trees per period photographs and these excavations have revealed charcoal and other features that may line up with the orchard. Many nails as well as some ceramic sherds and glass have been found during the excavations, though they all date to after the 17th century. One of the finds includes sherds of a jar lid made of milk glass, a type of glass used in the early 20-century. Stay tuned for more information in future updates as the dig progresses in this area.

In the field north of James Fort, excavations are also planned to continue in an area where several ditches and one of a series of subfloor pits should intersect. The hope is that a diagnostic artifact will be found in one of the features, one that will help date it. Also, if the features intersect as they should, the archaeologists will be able to use relative dating to determine their temporality. Because newer features will always cut older ones, these excavations may help us date both the pits and the ditches. So far the pits have been largely devoid of artifacts, which can mean the feature is early, but we can’t be certain as of yet.

A classic example of a diagnostic artifact in a colonial Virginia context is a pipe stem, which can be dated by measuring the diameter of the bore hole of the stem, with characteristics such as bowl size and stem length also useful in the dating process (though often a sherd of the stem is all the archaeologist has to work with). These excavations have the potential to be an important piece of our understanding of the colonists’ efforts north of the fort area.

Another proposed site on the list for 2025 is a 15′ x 5′ rectangle just east of the present dirt road where ground-penetrating radar (GPR) loses the “Zuñiga map” flag ditch. The ditch, a 1608 feature present on the Zuñiga map of Jamestown, is represented by a flag-like drawing protruding from the fort’s northern bulwark. Using GPR and excavations, the team found much of the ditch, but as they followed its turn westward, it became harder to find. The hope with these excavations is to pick up the ditch’s trail again, which appears on the map to include some sort of enclosure.

Shifting to the east, just a few yards north of the Pocahontas statue, two 10′ x 10′ squares near a cellar are on the agenda for the warmer months. The cellar, found in 2024 via GPR surveys by both Field School students and Kids Camp attendees, is brick-lined and is on the property of John Howard, a tailor who patented land here in 1694. We’re not sure if this cellar is related to Howard or if it was built before or after his ownership. GPR and previous excavations revealed several burials in the area, at least one of which appears to transect the cellar. Similar to the north field features, determining which features cut through which will inform us if the burials or the cellar are older. The two planned squares here will hopefully give some clarity to the nature of the cellar and help determine if further excavations are warranted.

In the fall four burials are set to be excavated, three in the 1607 Burial Ground and one in Smithfield. The colonist excavated from Smithfield in 2024 was in poor shape, and was originally interpreted as a child. However, further analysis suggests this person was actually an adult. The severe degradation of the human remains in Smithfield is cause for concern, as usually adult human remains survive well in the ground at Jamestown. This year, the team plans to excavate another adult in the same environment, to see if the remains are in the same poor condition. If they are just as degraded, the team will have to weigh whether more excavation will be useful or not. Does the limited data that can be obtained from largely dissolved remains warrant the team’s efforts, particularly when many other archaeological

resources are also threatened by flooding? The condition of this second adult colonist excavated this fall will help answer these questions.

In the Jamestown Rediscovery Center, archaeological staff are helping the curatorial team pick through material from Pit 1, found in 1994 shortly after the project began. The material has been “floated”, or separated by buoyancy using water and fine screens. After flotation, the team sifted the heavy fraction (the portion that sank during the flotation process) through several screens, with mesh as fine as 1mm to catch the smallest artifacts. This smallest mesh has caught artifacts such as seeds and beads while screens of 2mm and larger have caught sturgeon bones, nut shells, glass, crucible sherds, lead shot, lithics, copper, and burned wood. After Pit 1 is complete, the team will then turn their attention to Pit 5, a feature found just outside James Fort’s 1608 addition that expanded the walled settlement to the east. The east bulwark trench and Pit 3 have already been completed. Senior Curator Leah Stricker is currently picking through the light fraction, the portion of the objects that floated to the top during the flotation process. The features that are being chosen for this process are those that are being analyzed as part of a Surrey-Skiffes Creek grant focused on faunal remains.

Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp is processing the final bag of excavated material from feature 2718N, one of the layers of the fort’s first well (the “John Smith Well”). She is separating faunal material from other objects such as brick, glass, and lead. She is then separating fish from other faunal material to prepare for their analysis by outside zooarchaeologists Steve Atkins and Susan Andrews. Mr. Atkins’ specialty is fish and Ms. Andrews concentrates on everything else.

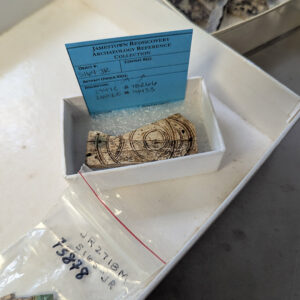

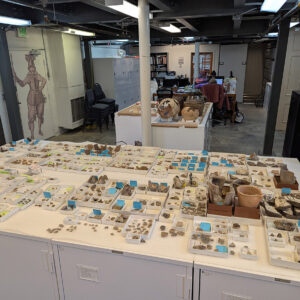

Inside the Vault, Senior Curator Leah Stricker and Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens continue their work on the crucible collection as part of the wider reference collection efforts. Before the work on crucibles began in the fall of last year, there were only 10 known crucibles in the collection. After a few months’ work the count is now up to a minimum of 60. The collection contains over 2000 crucible sherds and Lauren has made many mends over the past few months. To help with their cataloging and mending efforts, sherds are grouped by their location on the vessel, such as rims and bases. Most of the crucibles in the collection are of a triangular shape indicative of manufacture in Hesse, a state in present-day Germany. Hesse was known for its high quality crucibles able to withstand very high temperatures. Many of the crucibles in the collection were cross-mended from different contexts, meaning various sherds of a single vessel were found in different locations in and around James Fort (cross-mended crucibles are marked by a blue tag in this photo). As she catalogs each sherd in the database, Leah is also noting the residues on their surfaces, evidence of the colonists’ metallurgical and glass making efforts.

Prior to doing any kind of digging at Jamestown, whether it be building construction or planting flowers, archaeological excavations need to be conducted first. Construction of a storage shed built in 2020 and located between the Jamestown Rediscovery Center and the Archaearium museum didn’t begin until preliminary archaeology on its proposed footprint was completed. Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford is writing the report for those excavations now that most of the team is inside for the winter. The excavations revealed the presence of two burials, likely a continuation of the graveyard found a few feet away at the Archaearium that extends at least partially into Smithfield just south of the museum. They also found two modern utility trenches and part of a fenceline, likely dating to the 19th century, another portion of which was found in prior excavations just north of the Archaearium. As a result of the excavations, our maintenance crew knew exactly where the burials were and avoided them when placing the foundation. Associate Curator Emma Derry is cataloging the artifacts found by the archaeologists during the shed dig. While it was mostly a mixture of modern trash and 19th- and 20th-century artifacts, Emma’s work will be integral for the final report. If you’re interested in learning more about these excavations, you can watch Dig Deeper episode 24: “Laid to Rest : Final Finds at the Dead Shed.”

In the lab, Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe is conserving Jamestown’s collection of diptych dials. The ivory artifacts are a sundial and compass in one, with two main ivory leaves joined together, via copper-alloy bindings, that open and close similarly to a flip phone. Because many of the diptych dials are in a fragmentary state it is hard to know how many we have . . . it’s difficult to say with certainty that two non-connecting pieces are part of the same object even when their form suggests it. With that said, it is probable that we have 5 or 6 diptych dials in the collection. The initial part of Jo’s work is a condition assessment . . . to see where things stand currently and address any issues. This is an important part of conservation. Even though an object may be stable after its initial conservation, our conservators do condition assessments of artifacts both in the Archaearium museum and in the collections storage in the Vault at set intervals. You can’t take a fix-it-and-forget-it approach to artifact conservation.

Archaeological conservation is a constantly-changing field, with new and better methods coming to the fore with experimentation as with any other scientific field. When the diptych dials were first conserved, they were coated with B-72, a resin that is widely used in archaeological conservation to protect artifacts from potentially damaging interactions with the environment. Now it is known, however, that covering ivory in B-72 prevents the organic material from “breathing,” that is allowing moisture to freely come and go from the material. Preventing this transfer by sealing the artifacts can lead to cracking. So one of Jo’s first tasks was to remove the B-72 sealing the ivory. Luckily B-72 is a reversible sealant which is one of the reasons it’s used so often in conservation. She then did a quick run of an acetone-dipped swab across the surfaces to remove foreign substances. She tries to minimize the time acetone comes in contact with ivory because it draws moisture out of the material, potentially damaging it. Jo has several scalpels of various sharpnesses, choosing a relatively dull one and working through the lens of a microscope to remove the B-72 from the manmade etchings on the ivory’s surface. Where the copper-alloy bindings still exist, she is coating those in B-72 to prevent further corrosion. Read more about diptych dials, how they were used to tell time, and how they were constructed here. Oxford’s History of Science Museum has an excellent video describing how these work, using a contemporary example in its collection.

When we hired Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb, we were getting not only an excellent archaeologist but also a talented artist. Eleanor was a student of 2023’s field school and we were happy to have her join the team last year after her college graduation. During the winter months she has been working on drawings of the human remains from 2024’s burial excavations. The display of human remains is sensitive for many reasons, whether they be actual bones in a museum or photographs on a website. Part of Virginia’s Department of Historic Resources’ (DHR) agreement with Jamestown regarding burial excavations mandates that they must be out of the public eye. This is one of the reasons a burial structure is built to house the archaeologists during the process. Given Eleanor’s artistic gifts, the archaeology team thought asking her to create drawings of the colonists’ remains might give us a tool to display accurate representations of them in cases where showing photos of the remains is inappropriate. She uses a grid to ensure the accuracy of her drawings and India ink which, once dry, is waterproof and appropriate for archival purposes. To obtain shades of gray, she dilutes the ink with water. Depth and shadows are portrayed with stippling (dots) and hatching (lines). Eleanor wrote a blog post about the process for those interested in learning more.

Another project Eleanor is lending her artistic talents to is enhancing Jamestown’s spade nosings webpage. Nosings were the iron “business end” of a spade and over 100 of them are in the Jamestown collection. Many of the nosings have maker’s marks impressed into them but they are difficult to make out in the artifact photos, which is where Eleanor comes in. She is drawing the maker’s marks using high resolution images as a guide to aid her. Where these photographs don’t give her the detail she needs, she is studying the artifacts themselves, stored in the “Dry Room” where temperature and humidity are kept within a range that inhibits corrosion. The maker’s marks include hearts, gauntlets, and asterisks and her artwork has been added to the spade nosings webpage, which you can view here. She will now turn her attention to drawing the maker’s marks found on Jamestown’s axe collection.

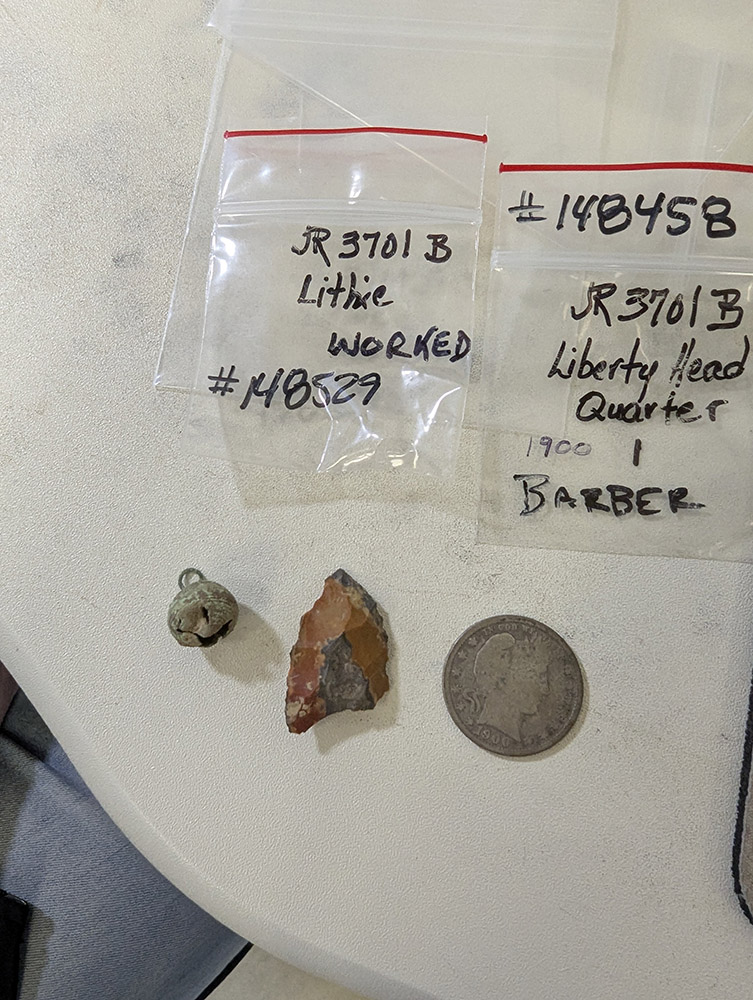

Our collections volunteers have been busy sorting and cleaning artifacts from various contexts to accompany the reports being written by our archaeologists. While processing a fill layer north of the Memorial Church the volunteers found a 17th-century button, a projectile point, and a Barber quarter dating to 1900. They are also working on artifacts excavated from last year’s dig south of the Archaearium. While working through that material they found a sherd of Bleu Persan ceramic, manufactured in England ca. 1680-1710. This fragment is the only example of this style in the Jamestown collection.

dig deeper

related images

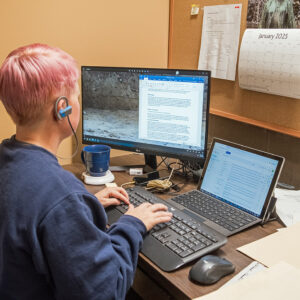

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas works on a report for recent excavations.

- Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch takes measurements of the different soil layers at the Godspeed Cottage excavations.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber displays a tiny bead he found while picking through excavated material from a past dig.

- Associate Curator Emma Derry picks through tiny material from Pit 1 caught by a 1mm screen.

- Two beads Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber found while picking through excavated material from a past dig.

- Sorting trays used by archaeologists and collections staff while picking through excavated material

- Some of the sorted artifacts found in Pit 1

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis points to a burn feature found in the excavations outside the Godspeed Cottage.

- A partially-mended diptych dial under conservation by Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker looks for potential mends in our crucible collection. Examples of partially mended crucibles are in the foreground.

- A mended crucible of the triangular style manufactured in Hesse, in present-day Germany.

- Jamestown’s collection of crucibles. Vessels with a blue tag are comprised of fragments found in multiple contexts.

- Two trays of artifacts sorted and cleaned by collections volunteers in January

- At center is a sherd of Bleu Persan ceramic, part of a tin-glazed English late 17th- to early 18th-century vessel. This fragment is the only example of this type in the Jamestown collection.

- The 1608 church (foreground), 1680s Church Tower, and Memorial Church on a snowy day in January.