The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeology team is finishing excavations inside the 1680s Church Tower in preparation for a glass floor installation that will allow visitors to view the foundations of the Tower and a portion of the 1617 Church’s western foundation. This floor and portal are part of a larger tower exhibit that is under construction this spring. The archaeologists’ tower excavations were partly to clear the way for the concrete supports necessary for the construction of the framework for the archaeology-viewing portal. However, they were also hopeful that a targeted investigation would discover details to answer lingering questions remaining about the churches on the site.

Engineered plans for the exhibit floor and portal included the careful excavation of two narrow trenches oriented north-south equal distance from site’s star feature — the 1617 Church foundation. The one-foot wide trenches allowed for testing and sampling of the top few inches of charred topsoil, thought to relate to the burning of the church during Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Within the narrow confines of the trench, Field Supervisor Anna Shackelford and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid also tested into the central portion of two large postholes that cut through the burned layer. When Senior Staff Archaeologists Sean Romo and Mary Anna Hartley referred back to the map of previous excavations, they identified three postholes outside the Tower to either side that matched the new features’ size, shape, and fill composition. One theory put forward by the team is that the postholes supported scaffolding used in the repair or deconstruction of the timber-framed belfry after its fiery demise in 1676. Further investigation of the posts on the exterior is needed in future to prove this theory.

In addition to the narrow trenches, the team choose to dig two tests into the interior builder’s trench for the Tower. Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas dug into the Northeast corner builder’s trench, while Anna Shackelford tested the southwestern corner. Both tests extended to the bottom of the builder’s trench, revealing that a spread footer was present on three of the four interior walls of the Tower. The team was surprised at the care taken by the masons, who took the time to clean and score the mortar for every course below the ground surface. A wide builder’s trench on the interior of the east and west walls made this task easy. The more narrow builder’s trenches on the north and south interior walls would have been harder to reach, but were still relatively tidy.

The two builder’s tests unearthed numerous fragments of mortar, timber-frame plasters fragments, tobacco pipe stems and fancy glassware which likely had littered the site during the Fort period (1607-1616) before the 1617 Church was constructed. The archaeologists did uncover three window leads, which when opened by the Conservators both revealed a date of 1671, then crossed “V”s followed by a “W.” These letters represent the name of the glazier, a craftsman whose job it was to install glass into windows. A theory as to why glaziers imprinted these marks in the lead channel that holds the glass panels (which would typically never be seen) is that they were a way to identify the glazier for quality control purposes. Using too thin of a lead could (and did) cause windows to fall apart. Inspections and court proceedings could mean fines for glaziers spreading their leads too thin. The immediate benefit of the leads to our archaeologists is their date. Because the leads were found in the Tower’s builder’s trench, the Tower’s foundation (and everything above it) could not have been built before 1671. This is an important archaeological concept called terminus post quem (TPQ), where a dateable feature or artifact provides the earliest possible date for another feature or artifact. As an example, an undisturbed pit containing a 1980 penny couldn’t have been dug in 1970. The discovery of these dated window leads disqualifies theories that the Church Tower was built earlier.

Despite disturbances by the multiple iterations of churches, archaeologists anticipated finding a section of 1607 James Fort’s eastern palisade surviving within the Tower’s footprint. They were rewarded with an approximately three-feet-long section that was full of material dated to the very early years of the colony. This included an intact glass bottle, only 2.19 inches tall, and one of only a handful of intact glass or ceramic vessels in the collection. Soil from within the bottle was carefully collected and saved by the conservation team, in case there is any surviving residue that could identify the bottle’s original contents. A large number of sturgeon scutes were also found in the palisade trench. These bony plates are primarily found in contexts dating to the first few years of James Fort like the palisade trench. To the surprise of the team, the palisade trench stopped next to a very deep posthole. This posthole is very likely a support for a gate, meaning it marks one of the original entryways into James Fort!

A large number of other interesting artifacts were found during the Church Tower excavations. Several copper alloy straight pins were found within the builder’s trench. These artifacts could have been dropped on the ground at some point before the Tower was built, but more likely came from early 17th-century burials disturbed when the building was erected ca. 1680. The team also found a copper alloy aglet. Since copper is naturally antimicrobial, copper alloy artifacts can sometimes contain or preserve organic materials. In this case, the aglet actually contained 17th-century thread! Other items found during the work were Native American ceramics, a copper alloy chain, and an iron knife blade. Chunks of plaster — several with impressions from wooden lath, dating them to the 1617 Church — were also found, as was a shaped brick with mortar consistent with that used in the 1640s Church. The team will be working with the Rediscovery conservators and curators in the coming weeks to tease out as much information about the chronology of the Tower site as they can from the artifact assemblage.

Excavations elsewhere were halted so that the team could finish the Church Tower dig before construction began on the new floor. Now that the Tower project is complete, work can resume in other areas, including in the excavation structure adjacent to the ticketing tent. This month, the delft drug jar was removed and brought into the lab for conservation. A lead gaming die was also found in this area.

One of the major goals of this dig is to investigate the junction between the churchyard and the surrounding town, to help pinpoint the location of 17th-century properties nearby. This is part of a multidisciplinary project at Jamestown Rediscovery using archaeology, property records, documentary research, and historic maps. You can learn more about these efforts by reading the October 2023 Dig Update. In the excavation tent, the team has recently identified a possible fence line that appears to mark the eastern end of the churchyard, a major find. Surprisingly, several large postholes have been found in the same area, which seem to mark the location of at least one 17th-century building. More excavation here is planned for March, so stay tuned!

The Jamestown Rediscovery team was also visited by masons from Colonial Williamsburg, who stopped by to examine bricks deconstructed from the walls of the ca. 1617 Governor’s Well. Masonry Trades Manager Josh Graml, Journeyman of Masonry Trades Kenneth Tappan, and Brickmaker’s Apprentice Madeline Bolton leveraged their skills and experience — having made thousands of bricks using historic techniques and tools — to “reverse engineer” the bricks from the well. The masons were able to offer insights into the tools and methods used to make the well bricks, which left distinct impressions and marks on the bricks. For example, deformation on some bricks was caused by “flinging the bricks out of the mold too quickly.” The masons’ information is an invaluable addition to the Rediscovery team’s understanding of the well’s construction. Study of the bricks has revealed that many have unique or informative impressions. Two have the imprints of hundreds of raindrops, indicating a storm came through before they were dry. Three others bear impressions of bird footprints, one identified as from a wading bird, possibly a heron. If these footprints are from species native to Virginia, it will definitively prove that the bricks were made locally. A plant’s impression dominates the face of another brick, and another bears a person’s thumbprint, a literal “personal touch” from a 17th-century brickmaker. Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid produced an in-depth writeup of the masons’ visit, which can be read here. Many thanks to Masons Graml, Tappan, and Bolton for lending us their expertise.

William & Mary geology professor Dr. Chuck Bailey has graciously offered to examinine a sample of rocks found in the bottom of the Governor’s Well. Director of Archaeology David Givens and Senior Staff Archaeologist Dr. Chuck Durfor brought some rock samples to Dr. Bailey’s lab for analysis and discussion. Dr. Bailey used a tile saw to create cross-sections of one of the rocks to allow clearer inspection of it under a binocular microscope. Dr. Bailey was struck by the fact that he couldn’t immediately identify the rock and theorized that the it is probably not of local origin. Further investigation and chemical tests are ongoing. Stay tuned for the results.

Virginia Indian ceramics are among the most common artifacts found by the archaeologists at Jamestown, a testament to the multitude of interactions between the Indian tribes and the colonists. A long-standing conundrum faced by the Jamestown archaeologists (and archaeologists more generally) is how to positively identify where Native ceramics were made. Knowing this would be an immensely useful tool in determining who the colonists were receiving food and goods from, whether via trade or by force. Additionally, if the team were able to date the feature where the pottery was found, they could then track the interactions through time. For pottery that is similar in form or clay composition, pinpointing its origin is difficult. David Givens, Director of Archaeology for Jamestown Rediscovery, theorized that single-sided nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) might be a helpful tool in this process. Dave and Dr. Chuck Durfor approached Dr. Tyler Meldrum, a chemistry professor at William & Mary and an NMR expert, about the possibility of testing samples of Native ceramics using the technology.

The team was lent samples of ceramics from two locations in Tidewater Virginia with the blessings of the local tribes. Dave and Chuck will return the ceramics in the same condition they received them because single-sided NMR is non-destructive. Single-sided NMR uses magnets and electromagnetic radiation to place nuclei in an excited state. For our tests, we are interested in the relaxation time, the time it takes the nuclei to return to their normal energy state after the excitation. The test involves submerging the ceramics in water and measuring the water’s response to ceramics of various origins (different porosities). In single-sided NMR, the proton relaxation time is dependent on the porosity of the sample. The team’s theory is that this relatively new technique may have value in determining the location and methods of manufacture. Thus, by measuring porosity we might be able to identify a certain pot found at Jamestown as being from Nansemond territory or Patawomeck territory for example. Dr. Meldrum has been kind enough to share his time, expertise, and the equipment at William & Mary to conduct some proof-of-concept tests with the different samples. The single-sided NMR machine returned results with our samples, which was a question in and of itself, and was the first step in determining whether this theory was viable. Dr. Meldrum, Dave, and Chuck are analyzing the results now and these dig updates will follow this ongoing process.

In the Vault, Senior Curator Leah Stricker is working with volunteers to sort material that went through the flotation process (watch this video to learn more about flotation). Leah is looking for botanical material like seeds and nut shell fragments under the microscope, while volunteers sort other artifacts from the samples. Funded by a Surrey-Skiffes Creek grant, Leah and the volunteers are working on samples taken from the site in the 1990’s and early 2000’s, including samples from Pit 1, Pit 5, and The Quarter. Most recently, artifacts from a Pit 5 sample included bone and glass beads, lead sprue waste from a gang mold, animal bone, and a sword hanger, an iron hook used to hang a sword in its scabbard from a sword belt worn by a soldier.

Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens has focused much of her attention in February on Spanish olive jars. Olive jars were used to hold many different types of food and drink including beans, chickpeas, wine, and olives. Lauren has searched through the archives, finding olive jar sherds which she will then sort, catalog, and see if they might mend to each other or existing vessels.

Collections staff from George Washington’s Ferry Farm visited Jamestown this month to examine the carnelian beads in our collection. Archaeologists at Ferry Farm have uncovered a single tubular carnelian bead that is part of current research into the enslaved population at that site, and they were eager to see the Jamestown assemblage and discuss Associate Curator Emma Derry’s ongoing research into lapidary beads at Jamestown. Although there are various sources of carnelian in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe, India has been the primary manufacturing center of carnelian beads traded far and wide for millennia due to a local abundance of the mineral and expert craftsmen quickly producing high quality beads. At Jamestown, stone beads are associated with the English colonists and may have been personal belongings or high status trade items. Many of the features where carnelian and other lapidary beads have been excavated predate the arrival of the first Africans at Jamestown in 1619. At later sites, such as the 18th century Ferry Farm, carnelian artifacts including beads were brought to America by enslaved West Africans who valued the beautiful stone as a protective charm against falling masonry and accidents with tools and believed it promoted healthy organs and blood. Talking with colleagues from other sites is a wonderful way to explore both continuity and change over time.

The breastplate pulled from the Archaearium last month is in a solution of sodium hydroxide in a bath that will last two months. This process forces the release of chlorides from the metal that are necessary for oxidation (rust). After its soak, it will be placed in silica gel to remove moisture. The breastplate, its form suggesting it was made as early as the 15th century, was found in the East Bulwark ditch. After conservation it will be placed back in its exhibit in the Archaearium.

related images

- Staff Archaeologists Natalie Reid and Caitlin Delmas (L-R) at work in the Church Tower. Natalie is excavating sturgeon scutes found in the 1607 palisade wall trench.

- A conglomerate of sturgeon scutes and soil found in the Church Tower.

- The section of James Fort’s eastern palisade wall found inside the Church Tower. An archaeologist has scored the outlines of the individual logs comprising the wall.

- A posthole found during the Church Tower excavations that was filled with brick and mortar rubble. This cut the ashen feature seen just to the west which was probably part of the remains of the wood framed tower burned during Bacon’s Rebellion (1676). This posthole was in turn cut by the Church Tower’s (1680s) builder’s trench so the feature has a rather tight timeframe.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas excavates an iron knife blade found in the fort’s eastern palisade wall within the Church Tower.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas holds the knife blade she excavated from the fort’s eastern palisade wall.

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis screens for artifacts from soil excavated during the Church Tower dig.

- A shaped brick found during the Church Tower excavations. Mortar consistent with that used in the 1640s church construction can be seen still attached to the brick.

- Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch holds a Nueva Cadiz bead found while screening soil from the Church Tower excavations.

- A piece of plaster found during the Church Tower excavations. Note the horizontal impressions made by a coupled structural element.

- The outline of James Fort’s 1607 eastern palisade wall can be seen oriented diagonally near the center of this photo. It suddenly stops at the center of the photo, and the archaeology team believes this marks the location of a gate. A tower found last summer just a few feet along the palisade wall to the north would seem to corroborate this theory.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford takes mortar samples from the base of the foundation of the Church Tower.

- Straight pins found during the Church Tower excavations.

- A collection of artifacts found during the Church Tower excavations.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley points to a brick in the Church Tower that bears a fingerprint.

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas at work in the Church Tower.

- Lead waste from a shot gang mold found in the Church Tower excavations

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid holds an animal hoof found in the Church Tower excavations.

- A copper alloy chain found during the Church Tower excavations

- A piece of coral found during the Church Tower excavations

- A copper alloy aglet found while screening soil from the Church Tower excavations

- Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch explains the latest discoveries in the excavation tent adjacent to the ticketing tent.

- A lead gaming die found in the excavations adjacent to the ticketing tent.

- The delft drug jar and lead shot gang mold waste just excavated from the excavation tent next to the ticketing tent.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber gently places the delft drug jar on a pan after excavation. The jar was found in the excavation tent adjacent to the ticketing tent.

- The delft drug jar and lead shot gang mold waste in situ. These were found inside the excavation tent adjacent to the ticketing tent.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford clean bricks prior to their examination by the Colonial Williamsburg masons.

- (L-R) Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley, Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens, and Colonial Williamsburg’s Journeyman of Masonry Trades Kenneth Tappan, Brickmaker’s Apprentice Madeleine Bolton, and Masonry Trades Manager Josh Graml discuss some of the bricks from the Governor’s Well.

- Members of the Jamestown Rediscovery team and Colonial Williamsburg Masonry Trades team discuss bricks from the Governor’s Well. (L-R) Director of Archaeology David Givens, Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford, Brickmaker’s Apprentice Madeleine Bolton, Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens, Associate Curator Emma Derry, Masonry Trades Manager Josh Graml, and Journeyman of Masonry Trades Kenneth Tappan.

- Director of Archaeology David Givens examines one of the bricks found in the Governor’s Well.

- A brick from the Governor’s Well with a bird’s footprint

- A brick from the Governor’s Well with the imprint of a plant

- A brick from the Governor’s Well with an apparent fingerprint

- A brick from the Governor’s Well with the imprints of raindrops

- William & Mary geology professor Dr. Chuck Bailey examines a slice of rock found in the Governor’s Well. Director of Archaeology David Givens looks on.

- William & Mary geology professor Dr. Chuck Bailey slices open one of the rocks found in the Governor’s Well for scientific analysis.

- A cross section of one of the stones found in the Governor’s Well after being cut by Dr. Chuck Bailey, professor of geology at William & Mary.

- Roanoke Simple-Stamped pottery (top row) and Townsend pottery (bottom row) from a Tidewater Virginia Indian site. These sherds will undergo nuclear magnetic resonance testing to see if the process can help determine clay source locations.

- Nansemond pottery found at a Tidewater Virginia Indian site. These sherds will undergo nuclear magnetic resonance testing to see if the process can help determine clay source locations.

- Artifacts found after flotation and screening of soil from Pit 5.

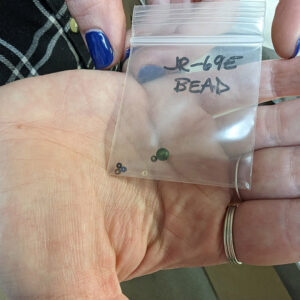

- Beads found by volunteers sifting through artifacts from Pit 3.

- An iron sword hanger found in soil samples from Pit 5.

- Olive jar sherds gathered by Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens for processing.