Archaeologists are following the trail of an early 17th-century ditch extending from James Fort’s north bulwark. This has led them to the moat of Confederate Fort Pocahontas, which they are carefully excavating to expose the earlier ditch. A few yards away near the Church Tower, the Jamestown Rediscovery team has found a second large pit a few feet away from the one reexposed last year that contained Native American ceramics and English brigandine armor. The northern sections of this area are being prepared for final record keeping prior to backfilling for the sake of preservation. In the Vault, curator Leah Stricker has been updating the collections database for Jamestown’s Spanish Lustreware, a rare type of ceramic in English colonial sites. In the lab, our conservators are working to conserve coffin hardware and 400-year-old textiles and are studying spectroscopic data from portions of our Virginia Indian ceramics collection in the hopes of identifying their points of origin.

Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists are deep in the moat of Fort Pocahontas as they continue following a 17th-century ditch that extends away from James Fort’s northern bulwark. Tracing the path of this ditch found by Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) earlier this year has run the team straight into Fort Pocahontas, a Confederate fort built to guard against Union ships moving up the James River. The team is now carefully scraping away the moat in order to get a profile of the James Fort-period ditch. The excavations are revealing a complicated array of digging and filling events that include the two forts built partially on top of one another and multiple landscaping efforts through the decades in order to provide better access to the Church Tower — and once it was found — James Fort. Luckily, earlier this month the team had the help of the students from our second Kids Camp. Helping to dig, screen for artifacts, and conduct GPR surveys, the kids learned archaeology fundamentals on the front lines of the Fort Pocahontas excavations. Artifact discoveries have been relatively sparse in the area this month. A few sherds of Virginia Indian ceramics, brick pieces, nails, and other small iron objects have been found recently. Senior Conservator Dan Gamble has been working on the iron object excavated from the moat last month during the Kids Camp. Unfortunately its thick coating of rust is preventing us from identifying it, even after Dan removed all the dirt underneath it. Further conservation will need to occur. For now this will remain a UFO (Unidentified Ferrous Object).

Over at the north Church Tower excavations the archaeologists have found a second pit, this one 3 to 4 feet in diameter. They have excavated the feature down about 4 inches and have found Virginia Indian ceramics, pieces of iron, lithics and lead shot. There is a postholes cutting the pit, surrounded by a thin layer of brick debris.. The fact that the posthole survives indicates that it was dug after the pit. A small white ball-like object is sticking out of the pit, its material and purpose as yet unknown. Another posthole about the same size was found just a few feet away, but with only two postholes it’s too early to determine if they’re related or part of a larger structure. In the northern part of these excavations the team is busy tidying up the side walls of the units, preparing them for photography and final record taking prior to backfilling the area. The area closest to the Church where the postholes were found will remain open, as the new pit and the one found last year containing brigandine armor and Native American ceramics will be excavated. James Fort’s eastern palisade wall went right through this area and some of its postmolds are visible in the soil. In other areas, just feet away, evidence for the expected line of the wall is muddled and obscured. This may speak to the fact that this section of the wall was short-lived, as it was removed during the 1608 expansion of the fort into a five-sided form. The wooden posts didn’t have as long to rot in the soil as they did in other sections of the fort and this may be why they are harder to see.

In the Vault, Curator Leah Stricker has been busy updating the collections database for Jamestown’s Spanish Lustreware. Spanish Lustreware was produced in Spain between the twelfth and eighteenth centuries and derives its name from the iridescent metallic oxides decorating the vessels. This decorative technique was brought to Spain by the conquering Umayyads via North Africa. There are only 7 partial vessels in the collection and Leah’s efforts have pulled these together for easier reference and study. Of the two most complete vessels in the collection, one is an escudilla (bowl) with two handles that features a bird and flower design. Because of its form, the bowl is thought to come from the town of Muel in Aragon, where other vessels of similar style were created. The Muel origin was confirmed by Neutron Activation Analysis, the tiny scars of which can be seen on the edges of some of our vessels. The bowl was found in a well in James Fort in use between 1608 and 1610. Moriscos — former Muslims who converted to Christianity to avoid deportation from Spain — were the primary producers of this type of ceramic. They were expelled from Muel in 1610 and that is the last year ceramics of this style were made. A second bowl in the collection, this one featuring a pinwheel motif, is similar to others found in Catalonia and Neutron Activation Analysis has also confirmed its Catalonian — more specifically Barcelonan — origin. Bly Straube, former Senior Curator for Jamestown Rediscovery, published her research on these vessels in Ceramics in America.

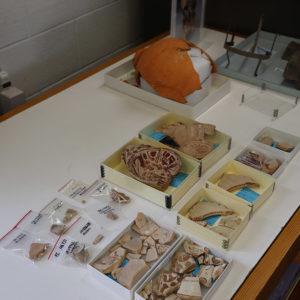

Senior Conservator Dan Gamble is conserving iron coffin hardware found in a late-17th century burial in Jamestown’s first brick church built in 1639. Amazingly, some of the coffin wood survived despite not being in a waterlogged environment or close to copper, both of which inhibit bacteria from consuming wood. Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins is working to conserve textiles found in the fort’s first well. Surviving 400 years in the well due to their anaerobic resting place underwater, the weave pattern and individual threads are visible. Chris is painstakingly separating the textiles from the soil surrounding them, made harder by the textiles’ small size and neutral color. He is also analyzing data from a Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) study of Virginia Indian ceramics in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection. The procedure takes a tiny sample of the ceramic and analyzes the individual elements. Hopefully the compositions can be matched to clay sources in specific regions, revealing the origin of the raw materials and possibly even the tribes that crafted the vessels. This could speak to the extent of trade between the colonists and Indians and as well as exploration by John Smith and others throughout the Chesapeake region.

related images

- The Confederate moat mapped through photogrammetry.

- Archaeologists at work in one of the squares containing the 17th-century ditch (darker stain in the center of the square).

- Campers sort artifacts found while screening the Confederate moat fill.

- A camper shares a find with visitors.

- A camper digging in the Confederate moat.

- Senior Curator Merry Outlaw identifies some of the finds from the Confederate moat.

- Archaeologist Brenna Fennessey teaches feature mapping techniques with a camper.

- Campers screening for artifacts in the fill from the Confederate moat.

- Archaeologist Josh Barber holds a sherd of Virginia Indian pottery found in the Confederate moat.

- A delft tile fragment found in the Confederate moat.

- The Unidentified Ferrous Object found last month in the Confederate moat.

- Field Supervisor Anna Shackelford prepares a feature for bisecting.

- The new pit, posthole, and ball-like artifact at the north Church Tower excavations.

- Measuring and recording a bisected feature in the north Church Tower excavations.

- Ceramics and lithics found in the north Church Tower dig.

- Field Supervisor Anna Shackelford holds two sherds of Virginia Indian pottery found in the excavations north of the Church Tower.

- Jamestown Rediscovery’s Spanish Lustreware collection

- A Spanish Lustreware bowl featuring a pinwheel motif

- A box containing soil and textiles from the fort’s first well.

- Textiles found in the fort’s first well

- Textiles found in the fort’s first well

- “Anas Todkill” gives the campers a living history lesson on the history of Jamestown.

- Field Supervisor Anna Shackelford teaches drone operation for archaeological photography.

- Assistant Curator Emma Derry shares the Jamestown Rediscovery’s delft tile collection with campers.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo teaches a camper how use the GPR.