Following the path of an early, possible fort-period ditch found earlier this year, the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists are excavating a section of the moat of Fort Pocahontas, a Confederate fortification built largely on top of James Fort. The team has made good progress on the moat dig thanks to the help of the 7 archaeologists-in-training who attended July’s Kids Camp. Several yards to the east, excavations continue on a square containing a grave that was first excavated by J.C. Harrington and the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1941. Erosion issues there are making completion of these excavations a priority. Although the dig just north of the Church Tower has been paused as the archaeologists focus on the other two sites, a review of some of the artifacts found there during the Summer Field School is giving new insight into the formation of one of the overburden layers in this part of the churchyard. In the lab, conservators are working on some of the recent finds from the field including a large iron object found in Fort Pocahontas’ moat and a leather object that could possibly be the tip of a scabbard.

The archaeologists are following a large, early ditch both north and south of where it was found just outside the northern bulwark earlier this year. There are two areas of excavation focused on this ditch separated by a modern walking path. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) first identified the ditch and indicated that it’s quite large both in width and length, extending several yards to the north before taking a nearly 90-degree turn to the west. Early excavations have confirmed the substantial breadth of the ditch on both sides of the walking path. The ditch’s run south takes it directly across the moat of Confederate Fort Pocahontas, built in 1861 largely by enslaved labor and designed to repel Union ships headed upriver. With the help and guidance of the staff archaeologists, the Kids Camp participants excavated large sections of the moat in order to define the edges of the ditch. While doing so they found both 17th-century and 19th-century artifacts including Bartmann jug sherds, bricks, Virginia Indian pottery, delftware sherds, window glass and lead, whiteware and a large as-yet-unidentified iron object that was carefully excavated and sent to the lab for conservation. During camp, the kids learned all manner of archaeological techniques from the Jamestown Rediscovery staff including using GPR to locate features, shoveling and troweling, recording the results of their excavations, and screening for artifacts in the piles of dirt they removed while digging. They also took a break from the heat and headed to the Archaearium to learn about the history of the settlement from “Anas Todkill,” a crewmember of Captain John Smith‘s expedition in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

Several yards to the east, excavations continue on an area previously excavated by J.C. Harrington and the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1941. There is a grave here and it was left intact by the previous archaeologists. Although protected from rain directly above it and around it by sandbags lining the square, rainwater is seeping through the square’s boundaries laterally — from within the soil — damaging those boundaries and threatening the archaeological assets within. This has made completing the excavations here a priority for the team. This area was also impacted by the construction of a road here in the 1950s. Evidence of excavations to level the ground and provide a stable foundation for the road can be seen in thick orange layers of clay in the square’s vertical profile. Below this orange layer lies a gray layer that is the backfill from the 1941 excavations. Despite the fact that this area has been excavated previously some early artifacts have been found, including a substantial sherd of Staffordshire slipware.

The dig just north of the Church Tower was put on hold for a couple of weeks in order to focus resources on the other two areas. However, Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley took some time to review of some of the materials found in each of the layers for clues as about each deposited. The most prominent layer — visually — was the rubble layer that showed up about half a foot down in each of the new units. This layer contain hundreds of broken bricks, with pockets of multiple types of mortar dispersed throughout the layer. Currently, the team theorizes that this rubble layer was part of a pile formed in the yard ca. 1800. Around this period is when African-American men enslaved by the Ambler and Lee families were salvaging complete bricks from the old church ruins, in order to construct a churchyard wall. Those bricks that were already broken or broken while removing the old mortar were discarded here in a pile.

Besides regular brick bats, the team found two decorative mullion bricks — that were used to separate two sections of a window — one complete triangular window pane, and lots of melted window lead. The presence of the window elements, plus multiple types of floor pavers, mortars, and plasters — comparative with both the 1617 timber frame church and two phases of brick churches — suggests that there was a cleansing of the area around the ruins going on simultaneously with the salvage project.

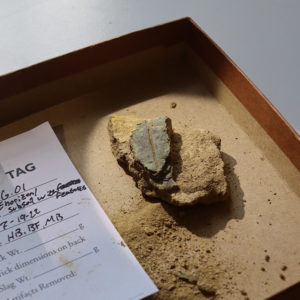

Notable among the artifacts currently being worked on by the conservation team are a piece of leather, possibly a scabbard chape, and a large iron object, both found in the moat of Fort Pocahontas. The leather object survived due to its proximity to copper, as the salts in copper prevent bacteria from consuming organic material. The leather object is stained green, another indicator of the presence of copper, though no copper was excavated with the artifact. On the last day of Kids Camp a large iron object was found in the moat. The object’s identity is currently a mystery but cleaning and conservation in the weeks ahead will hopefully shed light on its form and function. Due to its size and the time required to carefully separate it from the surrounding dirt, the artifact was removed from the ground along with the soil below and around it, a technique known as pedestaling. Now that it’s in the lab the conservators can take the time necessary to properly clean and preserve it.

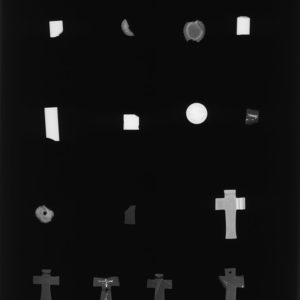

The Jamestown Rediscovery artifact collection contains dozens of artifacts made out of jet, a black jemstone formed from wood that has been compressed under intense geologic pressure. It can be difficult to differentiate true jet from other objects of similar color and form and so the conservation team had many of our jet-like artifacts X-rayed in an effort to provide further indicators of their makeup. On the X-ray images true jet appears as a dull gray while denser, non-jet artifacts appear brighter as the photons from the X-ray source can’t penetrate them. As the image shows, one of our crucifixes is not jet, as is the case for several other artifacts in the assemblage. The artisans creating these objects probably had similar trouble discerning jet from jet-like substances. Further research on our jet collection to investigate the origin of the raw material is planned in the near future. Sources of jet are relatively rare and a strong candidate is Whitby, England, since crucifixes found in Whitby made from local jet appear very similar to those in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection. Crucifixes are Catholic objects, so English examples were probably created before the English Reformation.

related images

- Director of Archaeology David Givens gives an overview of the excavations of Fort Pocahontas’ moat to the campers.

- Campers learning how to use the GPR with Director of Archaeology David Givens.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo discusses troweling techniques with a camper.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid watches as campers conduct excavations north of James Fort.

- Archaeologists and campers screening for artifacts

- A camper holds a piece of a brick with the initials “RF.” This is one of several such bricks in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection.

- Screening soil from Fort Pocahontas’ moat

- A camper holds a sherd of delftware he found while screening.

- A camper holds a sherd of delftware she found while screening.

- The large iron object found in Fort Pocahontas’ moat

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley holds two paver bricks found during the north Church Tower excavations.

- Plaster found in the north Church Tower excavations, some of which shows signs of burning. This may be attributable to Bacon’s Rebellion when the 1617 church tower was burned to the ground.

- Window lead fragments found in the north Church Tower excavations

- Triangular window glass found in the north Church Tower excavations.

- Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists filling sandbags used to protect the excavation sites from rainwater drainage. The dirt used for sandbags is screened for artifacts prior to usage.

- The northern and southern ditch excavations

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid leads a journal exercise with the campers.

- Kids Camp July 2022

- A camper holds a heavily rusted iron object he found during screening.

- Archaeologists and Field School students stand where GPR indicates presence of the ditch currently being excavated.

- Campers conduct Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) surveys inside James Fort.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid helps a camper document a feature.

- A camper conducting a GPR survey outside James Fort.

- Director of Archaeology David Givens teaches the campers how to read GPR data.

- Heavily rusted iron artifacts sometimes look like Cheetos. A camper brings hers out to compare.

- Campers sort artifacts from John Smith’s well in the Ed Shed.

- A camper shares his finds with some visitors.

- A whiteware plate that was discovered and pieced together by the campers on the last day of Kids Camp. The plate dates to the mid-nineteenth century at the earliest.

- Campers piece together the whiteware plate found on the last day of Kids Camp as Archaeologist Brenna Fennessey looks on.

- “Anas Todkill” gives the campers a living history lesson on the history of Jamestown.