Building the Jamestown reference collection for buttons

Jamestown Rediscovery, Ava Geisel

Jamestown recently said goodbye to Ava Geisel, who interned in Collections as part of her senior year at Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School in Richmond. We’re so glad she chose to spend the year with us and are excited for you to learn more about all the fantastic projects she took part in. Keep reading to learn more about Ava’s largest project: the button reference collection.

During my year-long internship with Jamestown, discussed in another blog post, I primarily worked on the button reference collection. A reference collection is a representative sample of an artifact. At Jamestown, this is a long-term project to identify, sort, and feature every type of artifact recovered in the project’s history. For small finds like buttons, this requires locating and examining every single button in the collection. Last year, this goal seemed like a very distant target because of how many there were (almost 900!) and how many material types there were (glass, copper alloy, iron, shell, bone, leather, ceramic, and synthetic). It’s a huge task! Working with the button collection taught me a lot about archaeology, history, Jamestown, and even fashion history.

I’ve always loved vintage clothing because of the history and story behind each piece that can be felt by just touching it or looking at it. I find that this is the same experience I have with historic artifacts. Whether it’s a ceramic or a button, there is information to be found in just looking at the object and a backstory that I think you can feel. The fun lies in figuring these stories out! My mentor during my internship was Janene Johnston, the Assistant Curator in the archaeology lab. As a curator she is vital in collecting and piecing together the artifacts to build the true story.

Creating the button reference collection began with gathering all of the buttons into one place, determining the different types, and rehousing them. Many buttons were already in one drawer, but there were approximately 150 that needed to be retrieved from the archive. So my first step was to hunt these down! I got to go through many, many artifact boxes and bags and see many different artifacts. Doing this gave me a sense of the collection and the archaeology that has been happening at Jamestown for the past 30 years.

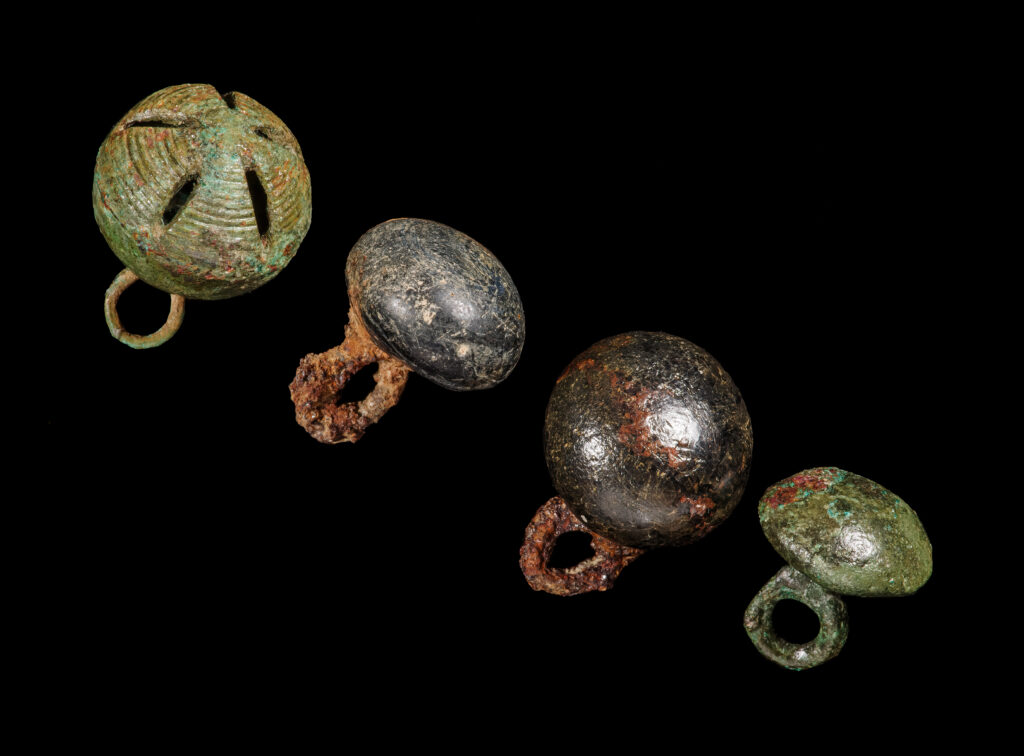

The next step was the most time-consuming and involved measuring and weighing each button, determining completeness, and rebagging each with a newly printed bag-tag. This allowed me to actually handle every single button in the collection and was the best way to gain insight on all the different types of buttons. I also did a preliminary sort of the button types based on their composition and form. Not only are there different material types and subforms of buttons, there may also be several different varieties of those types or forms. For instance, there are over 20 different types of copper alloy doublet buttons represented in the collection. The characteristics that Janene and I used to determine types included material, shape, manufacture, and decoration. We often consulted with Senior Curator Merry Outlaw – her extensive knowledge helped us ensure that we accurately identified all types and terminologies.

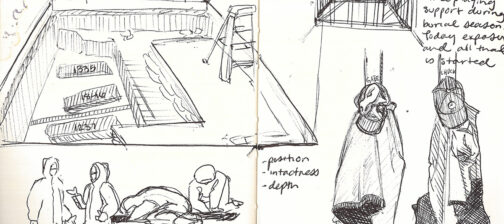

Figuring out which buttons to conserve was one of the more interesting steps. I liked seeing how Janene (a curator) and Dan Gamble (a conservator) had to work together to determine how much conservation an artifact needed and how their opinions differed on some buttons or aligned on others. Janene looks at information like the context the button was recovered from and how unique the button is in the collection, while Dan primarily considers material type and whether it’s stable or needs intervention. They both take into account whether or not conservation is necessary for identification and typing and then compare their rankings to determine the conservation priority.

One of my earliest duties was reading a paper on how to identify Prosser buttons. Prosser buttons are a type of high-fired ceramic button that is often confused with glass buttons. Then, I was given a group of suspected Prosser buttons which I attempted to sort into either the Prosser or glass category. Even after reading the paper I wasn’t confident in any of my choices and this task showed me how tedious and time consuming this work could be. I ended up being a little off from the actual identifications, but I really liked that I was given the chance to figure it out by myself. It reiterated to me how much expertise and experience play such a large role in archaeology and how the accumulation of these experiences leads to expertise.

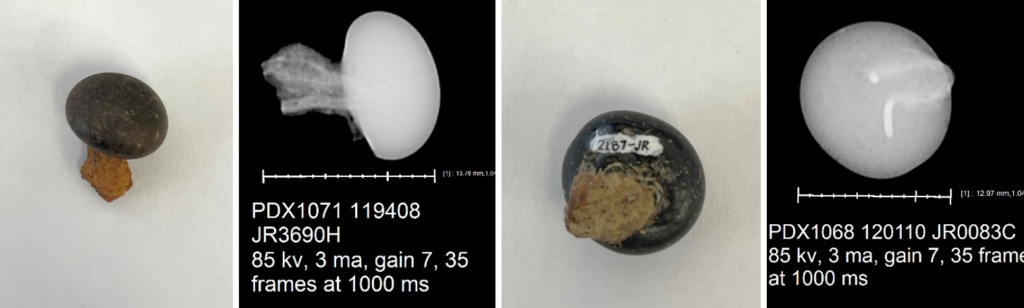

After completing all of the initial tasks, I began some of the more specialized tasks including photography and X-rays. Some of the glass doublet buttons had iron shanks that were corroded. This corrosion meant that we were unable to tell if they were complete. After I conducted X-rays of these buttons and processed the images, we were able to determine the buttons’ completeness. Some of the results were surprising compared to the visual inspection, as you can see in the photo above. Later on I also X-rayed the iron buttons. A lot of these buttons are not high enough priority to be conserved and the best way to capture their current state before further corrosion is through X-rays.

Luckily, I was able to tie up the button reference collection before my internship ended. The measurements, X-rays, photographs, and LIBS (laser induced breakdown spectroscopy) results that I took have been imported into the collections database. Janene input all of the analyzed characteristics into the database, which allows for all the information to be easily accessible and able to be analyzed digitally. We organized the button drawer and chose reference examples for all of the 17th-century buttons — all that’s left to do is decide on examples of the 18th-20th century portion of the collection and write website pages. I’ve really enjoyed seeing Janene’s process, hard work, and how this project fits into her role as a curator. This project has shown me how important small artifacts can be in a larger picture.

The evolution of fashion for men and women over the past four hundred years can be seen just through the evolution of the button and the materials and structures of each type. Without fabric to depend on, archaeologists have to focus on the artifacts left behind from clothing to figure out what these pieces looked like and how these people lived. For instance, while we do have a large number of fairly plain doublet buttons, there are a few sets that appear to be from garments belonging to those of high status individuals.

I am so incredibly grateful for the experiences I have had at Jamestown and the people I have met. This fall, I’ll start my freshman year at Fordham College at Lincoln Center in New York City and plan to major in anthropology and minor in fashion studies. My time at Jamestown has really influenced my career goals and my decisions for further education in such a positive way.

By Ava Geisel, former collections intern, now student at Fordham College studying anthropology.

Support for the creation of the button reference collection was generously provided by a grant through The Colonial Dames of America’s Education and Scholarship Committee.