In the early 20th century, as construction crews built the seawall around the western tip of Jamestown Island, they encountered a bronze bell fragment. They did not know it at the time, but they had just discovered a significant piece of early Jamestown history. Over a century later, Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists encountered three more fragments of the same bell at the James Fort site. One fragment was found in the west bulwark ditch of the fort, a feature that was backfilled by the colonists by 1610. If it once served as a James Fort church bell, then the archaeological context of the fragment suggests that this bell functioned inside the first church at Jamestown. The first church was near the center of the fort and stood from 1608 until 1617. In 1610 the secretary of the colony, William Strachey, recorded that the church had two bells in the west end. By 1617, it had fallen into disrepair and a new church was constructed nearby.

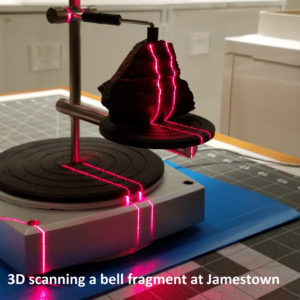

A couple of years ago the Jamestown Rediscovery team was approached by bellmaker Ben Sunderlin, the only traditional bellfounder in the United States, to inquire about reproducing the Jamestown bell. Fortunately, the surviving bell fragments represented different key components of the bell’s profile, which allowed Ben to understand its historic shape. The first step was to 3D laser scan the fragments, from which Ben produced 3D prints as guides to create the profile. Then armed with a wooden cut out of the bell’s profile he began building a two piece mold at his bellfoundry in Ruther Glenn, Virginia, the B.A. Sunderlin bellfoundry.

Jamestown Rediscovery staff made several trips to the bellfoundry to witness and document the various stages of the bell’s reproduction. “It’s truly amazing to see a piece of shattered history come back to life, but in this case you not only get to see it, you also get to hear it when it’s complete”, said senior staff archaeologist Danny Schmidt after visiting the foundry. The process took several months, and began with the complex construction of the mold by hand using a loam mix from horse dung, hair, water, clay and sand. Called the core, the first section, became the interior of the mold and inner shape of the bell.

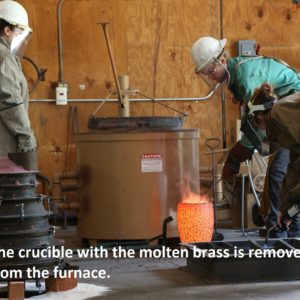

Next, a false bell is created using the same loam mix and the bell’s profile as a guide. The false bell was molded in the shape of the future bell, and then covered with a fine surface of wax. The wax coating made it easier for Ben to attach the crown to the top, and to build the final section of the mold with yet more loam to cover the false bell. Once the final section, called the cope, was complete the false bell was removed leaving a void between the cope and the core to cast the bell. In late July of this year, Ben and his team poured the molten bronze into the mold to cast the bell, and several days later they destroyed the mold to take their first look at the bell.

Currently Ben is in the process of refining the bell through a detailed grinding process, and the final product with be making its way to Jamestown in the coming months. Mr. Sunderlin remarked that “we are really excited to be able to reconstruct this bell and to hear and experience something that the early settlers of James Fort got to experience.”

This work would not have been possible without a generous gift from the Jamestowne Society who funded the rebirth of Jamestown’s earliest bell.

related images

- One of four fragments found belonging to the Jamestown bell.

- 3D scanning a bell fragment at Jamestown

- The crucible with the molten brass is removed from the furnace

- Casting the bell, the copper alloy is being poured into the two piece mold

- Removing the bell from the mold

- Removing the bell from the mold

- Working on the bell’s crown

- The Jamestown bell’s crown