In October, the Jamestown Rediscovery team focused exclusively on the eastern end of the Jamestown Memorial Church. They hoped to uncover evidence of the 1617 church’s east wall and to locate burials related to the chancel of that church. Excavations by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries uncovered the north and south foundations for the 1617 church, but not the east and west walls. Knowing specifically where the end walls of the 1617 church stood is crucial for pinpointing the exact locations of the chancel and “quire” [choir], where the first General Assembly met in July, 1619.

A year of excavating the entire floor of the 1906 Memorial Church and removing the APVA backfill helped us understand better what the former excavators did and how they left the site. Fortunately, Rediscovery archaeologists discovered that many of the structural elements noted by the APVA survived. Excavations also revealed that the APVA excavators concentrated in the chancel of the church, where they reported digging some of the burials. However, their descriptions of burial investigations both inside the church and out in the churchyard were ambiguous.

Mary Jeffery Galt and Richmond stone mason William Leal dug the first burial, which was located inside the church’s northeast corner. One report stated that raised tiles marked a grave in that area. In her field journal, Galt’s handwritten notes give some details of the skeletal remains and artifacts that they encountered in corner test:

“6th June 1901. Grave N.E. cor. Under Chancel- opened grave very large man- not cut his wisdom teeth- Shoulder bones 18 inches- nails of coffin handmade. Grave from floor of aisle 3 ft. to bottom of grave. Seems to be shallow grave. (“You can’t say but that’s a rotten as the Preacher” said Mr. Leal of length of time in grave.) Some large nails found and splinters of decayed coffin, large pieces of cement seems to have been layer of cement over coffin. 5ft 6/10 length of skeleton.”

Galt did not mention what happened to the remains after their discovery. Archaeologist Bob Chartrand discovered the bottom of the brick church’s north and east foundations and found little evidence of the skeletal remains described by Galt, which indicates they moved the remains to a new location, but didn’t record where. Subsoil was revealed at an approximate depth of three feet from the tiles that were removed in September.

Near completion of the test, Chartrand noticed that the backfill continued underneath the church’s north wall in one spot. Upon excavation, he discovered an intentionally dug hole under the foundation. In the bottom of the hole was a broken chancel paver upon which lay a rusted, oval-shaped iron box. What he located was a 1901 time capsule buried by the APVA for future archaeologists to discover!

According to Merry Outlaw, Curator, the object is a machine-made tin can, about 5” long, 3” wide, and 1-1/2’ deep, with a removable lid. “Unfortunately, because it was exposed to moisture for more than a century, any labeling on the can was obscured by corrosion. Based on its size and shape it is likely a tobacco or snuff tin,” Outlaw said.

Once in the lab, Rediscovery conservators Michael Lavin and Dan Gamble x-rayed the can and concluded that whatever it held was likely organic. The x-ray revealed that several areas of the thin metal had rusted completely through. When it was finally opened by conservators, they found a small, folded sheet of paper with crumbling edges stuck to the bottom of the can. Sadly, at the present time, the message is indecipherable. “It was really exciting to have found a 1901 time capsule and then really disappointing that the message in it was indecipherable,” lamented Chartrand.

related images

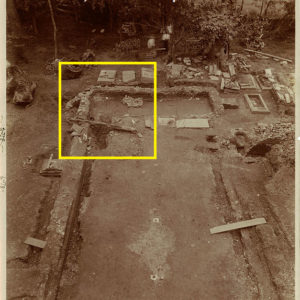

- This photo was taken June 1901, days after the APVA excavations started. The yellow box highlights the church’s northeast corner where the time capsule was buried.

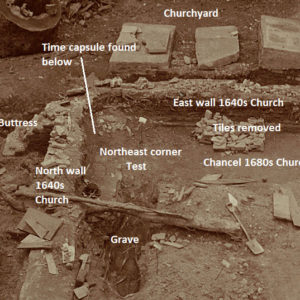

- Features in the APVA excavations

- Location of the time capsule in the church’s northeast corner

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand points to the small metal box tucked underneath the 1640s church’s north wall foundation. Rediscovery archaeologists believe that the box was left by the 1901 excavators and was intended as a time capsule.

- The excavated time capsule

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand removing the time capsule

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand holding the excavated box

- Visitors were able to see the moment of discovery streamed live by smart phone from the church’s northeast corner to the big screen TV in the west end of the church. Here, Bob Chartrand gives them an even closer view of the box moments after it came out of the ground.

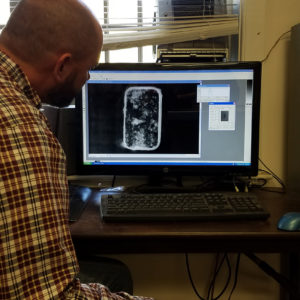

- Jamestown Rediscovery staff and Preservation Virginia colleagues from the Richmond office all gathered in the Rediscovery lab anxiously awaiting what the x-ray of the metal box would show about its contents.

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand places the metal box and tile into the x-ray machine to see if there are any clues as to what it might contain

- Conservator Michael Lavin examines the first x-ray of the metal box and determines that its contents are likely organic

- Conservator Dan Gamble and Bob Chartrand remove the time capsule from the tile fragment it has been resting on for over 100 years so that it can be opened.

- After the careful removal of some of the rust from the box’s lid, the team was at last able to peer inside at its contents.

- Photo of the folded sheet of paper lying in the bottom of the metal box. This is most likely a note left by the 1901 excavators shortly after they began their excavations of the church. Unfortunately, the paper is rusted through and any writing that might be on the page is unintelligible at this time.