The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists have discovered two furnaces built into the brick-lined wall of a cellar that dates to the early 17th century. This cellar was part of a building that stood just inside the western palisade wall of James Fort. While removing the fill above the layers occupied by the colonists, the archaeologists have found thousands of artifacts. In the same way that spoiled wells were used as trash bins by the early settlers, this cellar was filled with all sorts of rubbish once the structure fell into disuse. What the settlers considered trash has given us a glimpse into the life and culture of the early years of the Jamestown colony.

A layer of ash covering much of the floor of an early 17th-century cellar hinted at the presence of one or more fires at work in the structure. In addition to the hearth found last month, archaeologists have uncovered two furnaces just to the north along the cellar’s brick-lined eastern wall. The wall appears to have at least partially covered the northernmost of the two furnaces. It may have been totally covered over by masons once it was no longer used, or there may have been an opening in the wall to allow access to the oven. Not enough of the brick wall survives to know for sure. The other furnace’s base lines up neatly with the brick wall, indicating that it was in use when the wall was built. Though the brick is of local origin there are cobblestones below the brick that appear to be a type of basalt. Most likely these stones are English and would have been brought over as ballast during the trip across the Atlantic. It is unknown what the furnaces were used for, but there is a substantial amount of iron in the ash that covers the floor. Perhaps this points to industrial use, but there isn’t enough evidence to rule out cooking or other domestic uses, or even a mix of domestic and industrial usage.

The cellar has several different occupation layers—that is, levels of soil deposited while the structure was in use. These different occupation layers suggest that the cellar was used over several years. During its years of occupation, dirt and ash collected on the floor as a byproduct of day-to-day life and erosion. There is also evidence that the settlers deliberately raised the cellar’s floor on occasion to match the level of other parts of the cellar. At one point, it appears that the floor was raised so that the bottom step of a flight of earthen stairs met precisely with the cellar’s floor. A layer of fine gravel discovered under the ashy top levels of soil indicates that the colonists laid down a prepared floor at some point in the life of the cellar.

Postholes abound in the cellar and their substantial size suggests that there was, at one point, a heavy structure overhead. As with other buildings inside James Fort, this structure may have evolved from a slightly-built, relatively light structure into one built from more substantial materials. Different-sized postholes and varied posthole patterns support this theory.

During the excavation of the many feet of fill above the occupation layers, a numerous and varied array of early 17th- and late 16th-century artifacts have been recovered by the Jamestown Rediscovery team. An iron backplate—a piece of armor worn with a breastplate for protecting the back—was found, albeit with its top section missing. This is the latest in a long list of examples of adaptive reuse by the colonists. A neat cut removed the top section of the backplate, the fragment of which the colonists would have used for some other purpose. Armor developed in Europe was often found to be inadequate in the new surroundings. Heavy, fixed breastplates and backplates afforded protection against European swordsmen and musketeers on open battlefields. While also effective against Indian arrows, the swift surprise attacks from Virginia Indians meant that this heavy armor would have to be worn at all times if it were to be effective. The desire for protection against such a constant threat and also the stifling heat of Virginia’s summers had the colonists creating lighter, less-restrictive armor. Jack of plate armor, created by fastening together many small pieces of iron, was an adaptation to these conditions. It was less restrictive to its wearer’s movements and was lighter than plate armor as well. Several pits inside the fort contain evidence that the colonists cut up existing plate armor to create and/or repair jacks of plate. Plate armor was also modified to suit other needs completely. One example of this is a breastplate that was folded by the colonists to fashion a bucket or cooking pot.

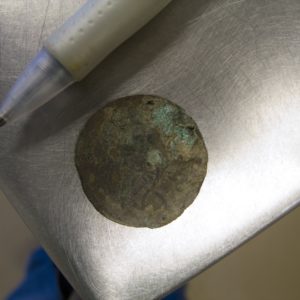

A “King’s Touch” token was recently discovered in the cellar. Stamped on one side with an intertwined rose and thistle under a crown, the token is one of over 50 found during the excavations at James Fort. Senior Curator Beverly Straube explains that in the 1940s, the British Museum identified these coin-like objects as King’s Touch tokens. The touch of the King (or Queen) was believed to cure the “King’s Evil” or scrofula, a disease of the lymph glands. The king would lay his hand upon the diseased area and bless the afflicted in a ritual set down in the Book of Common Prayer. The diseased person would then be given a “touch piece” as a token of the ceremony.

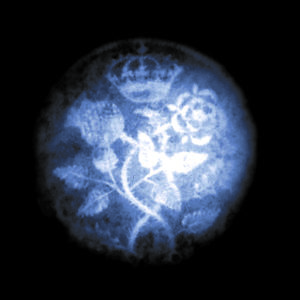

It is doubtful that these tokens relate to the Kings Touch ceremony since documented touch pieces are always silver. They may instead be tokens that were struck to commemorate the coronation of James I. The rose and thistle identifies the token with King James, who used this motif on the halfgroat, penny, and halfpenny to acknowledge the union of England and Scotland.

Several chunks of earth excavated from the cellar bear the imprint of corn cobs. These unique and fragile artifacts remind us of the importance of corn to the settlers and, during hard times, of their need to maintain friendly relations with their Indian neighbors in order to obtain enough of the crop. Some of the other artifacts recently found in the cellar include deer antlers, a rusted sword basket hilt, the base to a case bottle, the sole of a shoe, and a stirrup.

The Jamestown Rediscovery conservation team has made good progress on removing the rust from a broadsword found in the cellar in May. The sword blade is mostly intact and the basket hilt has a rather intricate design. The weight-balancing pommel is ball-shaped and made of two parts. As the wooden hilt rotted away, the blade and pommel shifted from their original position so that the pommel currently is housed within the hilt rather than outside it.

related images

- Trays of artifacts excavated from the cellar

- The King’s Touch token found in October

- An x-ray of a King’s Touch token found in 1996

- Iron backplate with missing top portion

- Pebble sample from the cellar floor

- A sword basket hilt found in the cellar

- Close-up of the broadsword’s hilt and pommel

- Deer antlers

- This broadsword was excavated from the cellar in May

- Another view of the broadsword

- Heavily-rusted stirrup

- X-ray of the broadsword

- Chunks of soil with corn cob imprints at left

- Breastplate fashioned into a bucket or cooking pot