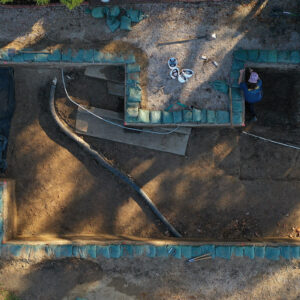

Just outside the Church Tower entrance, the archaeology team is excavating several squares to prepare for the installation of Church drainage and a new visitor pathway that will stretch from the fort area to the Archaearium museum. Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis is leading these excavations and has been using the backhoe to remove the backfill layers of some of the squares that were partially excavated in the first decade of the 2000s. The goal of these excavations is to record the location of archaeological resources so that the construction engineers know where they can (and cannot) disturb the soil. A portion of the proposed construction area was excavated previously, and the filter fabric laid over those excavations after they were completed in the early 2000s provides a nice boundary between archaeological resources beneath and backfill from the prior excavations above. Keeping an eye on the fabric, Ren is using the backhoe to save a lot of time and effort by removing the backfilled soil above it.

There are other sections here that are among the few areas within the original triangle-shaped fort’s bounds that have yet to be excavated. That is not to say that the area is undisturbed however. Being on the doorstep of the Church Tower has meant this area has been the focus of many construction projects which goal was to beautify the entrance, improve access for visitors, and provide utilities. The plethora of projects centered here through the years have left their mark on the soil, however, in the form of soil stains, pipes, and concrete steps and platforms.

Fort Pocahontas also left its mark here. The team thinks they have found the extreme eastern edge of the Confederate fort, which is an indicator of just how much of the 1607 fort’s archaeological footprint was covered by the 1861 fort’s earthworks. The team has also found soil layers that relate to the construction of a small road that passed right in front of the church. A number of thin scars in the soil here may be evidence of wagon wheel ruts. Because the excavation area is being shaped by the needs of the construction efforts, the outline of the dig is a bit unorthodox, being an asymmetrical mix of ten foot and five foot squares. A copper straight pin, mammal teeth and bones, and a decorative copper bar pin likely dating to the late 19th century are among the artifacts found in these excavations so far.

In the 1607 Burial Ground the burial structure is still up and the archaeologists are inside, finishing work on features discovered during the burial excavations. Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid is excavating a posthole thought to relate to a wine cellar discovered in 2004. This is the same posthole in which she found a copper alloy tack in the shape of a martlet (a mythical bird used in heraldry) last month. As with every other feature they excavate, the posthole will be mapped in GIS (Geographic Information System) software using surveying equipment so that the team and future researchers will know exactly where it is and what shape it took. This will give the team a bird’s-eye view of the posthole and nearby features, enabling them to see patterns that might indicate buildings or other structures.

Just to the west of the Archaearium, Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas is leading a team of archaeologists conducting ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys of the Statehouse remains and other features in the area. Like the excavations outside the Church Tower, upcoming site improvements are driving the dig here. This will be the location of the northern end of the new path that starts in the fort area. Additionally several interpretive and usability improvements are in the works here and before construction can begin, the team wants to know the location of archaeological resources so that they can be avoided during the upcoming projects. Caitlin and her team have finished 350 MHz and 900 MHz scans of the site, with the lower frequency scans giving more depth penetration but less resolution and the 900 MHz scans providing the opposite.

Collections Assistant Lindsay Bliss is sorting through the light fraction of floated soil from Pit 5, a possible cellar dating to ca. 1608-1610 and located just outside the eastern wall of James Fort’s five-sided expansion. She is looking through objects caught by the flotation machine’s 2mm and 1mm screens. Of particular interest to Lindsay and the curatorial team are botanicals, seeds and other plant remains that may give us insight into environmental conditions and the colonists’ diet. As the size of the screen mesh would indicate, these objects are tiny and Lindsay is using a microscope to facilitate the sorting. This month Lindsay found hickory nuts and persimmon seeds as well as insect remains.

Assistant Curator Lauren Stephens has dedicated much of her time over the past few months finding and curating architectural materials for Jamestown’s research efforts. After poring through the archives of the Vault’s second floor to find these artifacts, she spent part of October redoing the architectural materials reference collection. These collections are always potentially in flux, whether from new finds in the field or discoveries during research in the Vault’s archives. The architectural reference collection is populated with bricks, mortar, foundation cobbles, roof slate, and portions of mud walls.

This drawer of the architectural reference collection is categorized into four phases (1617-1639, 1639-1647, 1647-1676, and 1676-1758) that align with the dates of Jamestown’ churches and seminal events in the town’s life. Reference collections contain unique or representative examples of artifact types and are housed downstairs in the Vault for easy access to researchers. Should a researcher need to examine additional examples, these can then be pulled and brought downstairs. The most frequent users of the reference collection are our own staff, who use it to identify artifacts while they are cataloging. Housing the rest of the artifacts upstairs saves valuable room below where the team does the majority of their work.

Thanks to the work of curatorial intern Molly Morgan, the mending is complete on a Potomac Creek ceramic jar previously on display in the Archaearium museum. The partial vessel is substantially more complete and in a case of a problem that’s good to have, the existing mount is no longer sufficient to support the expanded pot. As a result, Lauren has amended the mount with two new arms, soldered to it to support the new sections. The improved pot will soon be back on display for our visitors.

Sorting the artifacts from the Seawall excavations led to the discovery of additional sherds of a Border ware fuming pot. The pot, the only one in the Jamestown collection, was manufactured in the border region between the counties of Surrey and Hampshire, England. Similar to today’s incense burners, herbs or fragrant wood was burned to mask bad smells, with the pot’s holes allowing the gases to escape and fill the room. Other pieces of the vessel have been found in the Powder Magazine, an early fort-period feature, layers associated with a midden, and Ditch 6, a later 17th-century feature found east of Memorial Church that may have been used as a property boundary. Lauren is mending the newly-found pieces. Hopefully future excavations will unearth additional sherds so our collections staff can continue to make the vessel more complete.

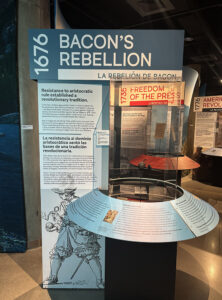

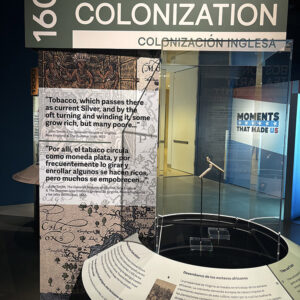

In October, Senior Curator Leah Stricker transported artifacts from the Jamestown collection to the History Colorado Center in Denver. A new exhibit entitled “Moments that Made US”, which opened November 21, includes 5 artifacts from Jamestown: two Robert Cotton pipes, and three grenade fragments. The pipes speak to the importance of tobacco to the success of Virginia and thus to the United States. Robert Cotton was a Jamestown colonist whose distinctive diamond-shaped fleur-de-lis stamp was impressed on his pipes. Using Virginia clay and a form that was closer to Virginia Indian pipes than European ones, he also used printer’s type to impress the names of Virginia Company of London leaders on some of his pipes. The exploded grenade fragments, found during excavations in and around the footprint of the Statehouse, are likely evidence of Bacon’s Rebellion, when on September 19, 1676 Nathaniel Bacon and his men attacked the Statehouse and other buildings, burning Jamestown to the ground. The exhibit is timed to coincide with the 150th anniversary of Colorado’s statehood and the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States.

related images

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford uses a backhoe to begin the excavations just outside the Church Tower as Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis looks on.

- To speed up the dig, Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis uses a backhoe to remove backfill from previous excavations just west of the Church Tower.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber shares some of the artifacts found while screening soil from the excavations just outside the Church Tower.

- The archaeology team at work at the excavations outside the Church Tower

- An overview of the excavations just west of the Church Tower

- Filter fabric marks the boundary between previous excavations beneath and backfill above.

- Mammal teeth found in the excavations outside the Church Tower

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis excavates some mammal teeth found in the excavations outside the Church Tower.

- Mammal teeth found in the excavations just outside the Church Tower

- Mammal teeth excavated from the excavations outside the Church Tower

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis excavates a mammal bone found in the excavations outside the Church Tower.

- A decorative copper bar pin found in the excavations outside the Church Tower. It likely dates to the late 19th century.

- A decorated pipe stem made of Virginia clay found in the excavations outside the Church Tower

- A drone shot of the excavations just outside the Church Tower

- A drone shot of the excavations just outside the Church Tower

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber at work in the excavations just outside the Church Tower

- Excavations of “The Quarter” in 1994 just outside the Church Tower. The concrete steps seen in front of the Tower have been uncovered in this month’s dig.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith disassemble the fence surrounding the Statehouse foundations in order to prepare for ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys of the area.

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith uses a reciprocating saw to remove a stubborn bolt during the disassembly of the fence surrounding the Statehouse remains.

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas remove part of the fence surrounding the Statehouse foundations. They’re preparing for ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys of the area.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith survey the Statehouse area prior to their GPR work.

- Staff Archaeologists Caitlin Delmas and Natalie Reid conducting a ground-penetrating radar survey of the Statehouse area.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas conducts a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey of the area just west of the Archaearium.

- Two Robert Cotton pipes on exhibit in the “Moments that Made US” exhibit in the History Colorado Center in Denver. These pipes are on loan from Jamestown Rediscovery.

- A drone shot of James Fort from the James River

- A flock of birds near the barracks inside James Fort