Through the removal of backfill from the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA) 1901-1902 excavation Rediscovery archaeologists have gained several new insights into the foundations of the 1617 church. One would think that because of its significance as the meeting place significance of the first General Assembly in July 1619, there would be a good deal written about the 1617 church. Instead, records about it are scarce. The only account of its construction states that it is “a church built wholly at the charge of the inhabitants of that city—of timber, being fifty foot in length and twenty foot in breadth.”

The 1617 church’s south wall foundation and portions of the north side have always been visible below the floor of the 1907 Memorial Church because the APVA left their long test trenches open along the interior. The floor of the 1907 edifice is low, and a black iron fence was installed to allow visitors to peek through to view the clay and cobblestones footing next to the brick foundations. The iron fence was eventually removed and replaced with glass portals, which existed until the recent excavations. Until now, no one realized how much the Memorial Church’s aesthetic and interpretive infrastructure impacted the 1617 foundations.

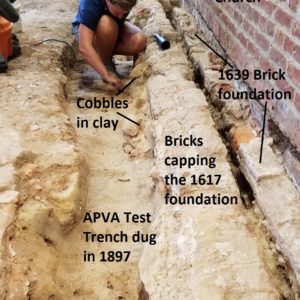

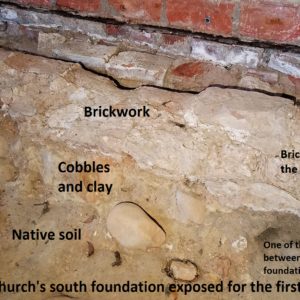

The removal of the early 20th-century backfill has helped clarify how the 1617 church foundation was constructed. The builders dug trenches approximately one foot deep into the dark native horizon down to about where the soil naturally transitions to subsoil. Into the trench, they threw cobblestones and very fine, waxy, canary-yellow clay that served as an excellent binder. The source of the yellow clay remains unknown, but it is very familiar to the Rediscovery team because it has been discovered in most of James Fort’s earliest features. Almost every backfilled well, cellar, pit, and dozens of postholes associated with early structures have contained this yellow clay in various quantities. Similar clay has been found in the deep subsoil layers well excavations, but has not been found in quantities large enough to be considered a viable source.

Mortared to the top of the foundation are bricks, which provided a level base for a wooden sill that was at least eight inches thick. Some of the mortar is bright white from the oyster shells temper, but in other sections the mortar is gray and very hard. It is uncertain whether there were one or two courses of brick sitting on the cobblestone footing. Excavations revealed that many areas of the original 1617 foundation were removed or robbed during the construction of the 1640’s church floor.

Recent examination of the APVA test trenches along the interior of the cobblestone footing revealed that the foundations are not continuous. There are gaps of native soil left at intervals along them. The foundations are broken into sections approximately 10 to 11 feet long, with native soil left in between the sections. Inexplicably, the brickwork capping the cobblestones and clay continues right across those undisturbed gaps. The mortar and bricks sit directly on the ground surface in those spots. Further examination and analysis is needed to understand why that is the case.

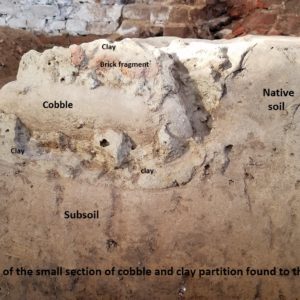

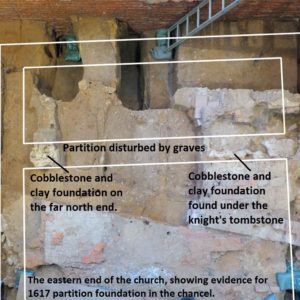

The most interesting new evidence related to the 1617 church was uncovered in the chancel. Hidden beneath the Knight’s Tombstone and partially disturbed by the APVA test under the stone, archaeologists found a cobblestone and clay foundation identical to those along the north and south sides. But this foundation was oriented north-south. Approximately four feet long, the section beneath the ledger stone was and was sealed by the brick church’s choir or chancel aisle floor. The middle of the foundation was completely destroyed by numerous later graves associated with burials in the brick church. Excavation of a small island of surviving 1640’s brick floor located directly north revealed another section of cobble and clay foundation, indicating that the foundation had originally continued all the way across.

Currently, the Rediscovery team theorizes that this north-south foundation was a partition of some kind, likely a step, between the chancel and the nave of the 1617 church. If true, the burgesses or representatives in the first General Assembly met in the area just to the west. The next step for the team is to continue their investigations in the chancel area and to sort out what different materials composed the floor for the chancel, choir, middle aisle, and the nave.

This month’s YouTube video shows the progress that has been made since November 2016, when the archaeologists began their excavations in the Memorial Church!

related images

- Early in 2017, Dave Givens and Bob Chartrand experimented with ways to map the 1617 wall. Later, the decision was made to remove all the concrete and iron portals.

- Photo taken kneeling where the Knight’s Tombstone was replaced by the APVA in 1092, looking northward towards the church nave

- Leah Stricker uncovers a small section of 1617 wall, in front of the south entrance to the Memorial Church, that has not been seen in over 100 years.

- Features in the church floor

- Features in the church floor including previous church foundations

- The 1617 Church’s south foundation exposed for the first time since 1902

- Amy Baker cleaning the south wall foundation for the 1617 church in the spring of 2017

- Back in 2015, Dave Givens examined cobbles in the 1617 church wall with Chuck Bailey (William and Mary) and then-student Kelsey Watson

- Leah Stricker finishes cleaning the 1617 church’s foundation just below the Memorial Church doorway

- Working in the chancel this fall

- Pictured is the profile of the small section of cobble and clay partition found to the north (looking north)

- Archaeologists point to the portions of the 1617 church cobblestone and clay partition running N-S across the chancel

- Leah Stricker excavates around a portion of the chancel aisle that survived from the brick church. This brick walkway was built over part of the 1617 church’s foundation.

- The eastern end of the church, showing evidence for 1617 partition foundation in the chancel