In June a new exhibit at the Voorhees Archaearium will reveal new details about the material world of Virginia’s Native peoples and their interaction with the English settlers.

“The World of Pocahontas Unearthed” will draw from thousands of archaeological finds that have reshaped our understanding of the lifeways of Chesapeake’s Indian peoples in the early contact period (1607-1614).

“For years we’ve had a very elegant museum talking about the English equation—the English side of the story—and clearly there’s another half. And that’s the indigenous, the Virginia Indian folks who were here,” said Jamestown Rediscovery Senior Staff Archaeologist David Givens.

The new exhibit will occupy the section of the archaeological museum at Historic Jamestowne where the slate tablet has been displayed the past three years. The slate and other artifacts from that area will be moved to elsewhere in the Archaearium.

Jamestown Island has a long history of Virginia Indians in the Chesapeake region, which is evident when studying the substantial collection of relevant artifacts. Algonquian structures were not secured deep in the ground, so evidence of their society remained at the topsoil level. Centuries of mechanized agriculture have disturbed almost all of the footprint the Powhatan villages left in the ground.

But James Fort was a large undertaking with many structures and many people moving through it for decades. Twenty years of excavations by the Jamestown Rediscovery Project have not only rewritten the story of the English community there but have also uncovered thousands of Native artifacts. A trove of Indian-made clay pipes and pots and stone tools have been found in the earliest living areas and trash deposits in the fort.

“That’s what archaeology does for you. It gets into the details and tells you the buried truth of what the past is,” Givens said.

For example, despite the fact that the Indians were receiving many iron tools in trade from the English, evidence from the excavations suggests that traditional Native techniques were not immediately abandoned. Givens pointed to a greenstone celt found in the fort as one such instance. Used as an ax, the celt mashes bark fibers as it fells timber, thereby producing the threads needed to produce grass netting or baskets.

“These have been used for thousands of years by the Virginia Indians, and the fact that we’re finding them still being used at the fort indicates that there are some tools—English tools—that don’t fit their needs,” Givens said.

“The story that we’re getting through these artifacts is not just the sheer volume of support—indicating women and men working here at James Fort—but actually indigenous or traditional tools that are still being used,” he said.

Another example of the interactions between the Powhatan Indians and the English are the hundreds of flaked stone projectile points found around the James Fort site. Powhatan Indians attacked the settlement many times—but arrows were also important symbols of peace and trade. The large number of relatively undamaged points made of non-local materials in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection is significant. The jasper and dark chert points are materials extremely rare in the gravels near Jamestown. Mottled jasper of this kind is common only in pebbles in areas such as the Eastern Shore and Virginia Beach—areas held by the Accomack, Chesapeake, and Nansemond groups at the time of English settlement. Dark chert typically comes from the Appalachian Mountains—in the territories of Siouan speaking groups. This evidence supports the idea that some projectile points came into James Fort as symbols of cultural exchange, not on flights of violence.

Givens also highlighted the 48,000 sherds of Virginia Indian pottery the Jamestown Rediscovery team has found within the fort’s historic features. One noteworthy example is a clay pot imprinted with a pattern of fiber from an Indian basket. The exhibit team has scanned the surviving pieces of this pot and fit them into a 3-D printing.

“So when you come to see the exhibit, you can actually see a Virginia Indian basket for the first time in over 400 years,” he said.

related images

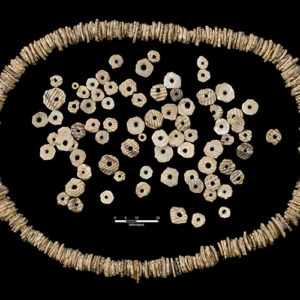

- Mussel Shell Beads

- A mended clay vessel made by English colonists, probably using an Indian basket

- The entrance to The World of Pocahontas, Unearthed exhibit

- The collection of Native artifacts in the Jamestown Rediscovery Project collection

- A panel from the World of Pocahontas, Unearthed