Jamestown was abuzz with investigations of the electromagnetic kind in March, both on ground and on water. While ground-penetrating radar (GPR) is a normal part of the archaeological process at Jamestown, the team was able to employ a lower-frequency antenna (200 MHz) thanks to the help of our partners at TerraSearch Geophysical. This included surveys in Smithfield, an area to the north and west of James Fort, where Captain John Smith drilled the settlers in the ways of war. GPR shows that the water table is only two feet below the surface there now, as evidenced by the fact that the field is often flooded. The team is eager to conduct archaeological investigations there before rising waters irreparably damage the features hidden beneath the surface. The lower-frequency antenna permits greater penetration into the ground than higher-frequency antennae. The lowest-frequency antenna that the Jamestown Rediscovery team has in their toolkit is 350 MHz. They will compare and contrast the data obtained using TerraSearch Geophysical’s antenna to that of the higher frequency antennae over the same areas to gain a more complete picture of what lies beneath Smithfield.

In a first for Jamestown, TerraSearch Geophysical also conducted a magnetometry survey of Smithfield. Magnetometry measures variations in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by the presence of iron. While iron artifacts are the most obvious “hit” that a magnetometer might pick up, deciphering subtler differences in soil’s iron content can be used to discover features below the surface. Topsoil typically contains greater amounts of iron than deeper soil due to the erosion of bedrock and wet/dry cycles on the surface. When features such as pits or ditches are built, they’re eventually filled back in, either intentionally or through neglect. This fill invariably has a different iron content than the undisturbed soil around the features. This is often due to sloughed-in or redeposited topsoil in the feature’s fill. These differences are what a magnetometer detects and indicates as archaeological features. When the magnetometry results are compared to GPR data for the same area, the team should have a very good idea of where to target their excavations. Cole Peterson, Geophysical Specialist at Heritage Consultants and Cassie Aimetti, Intern at Heritage Consultants, joined Dr. David Leslie of TerraSearch Geophysical to conduct the magnetometry survey. Because Smithfield has become increasingly flood-prone, the team will be focusing much of their efforts in this area in the coming years to recover what they can before water damages these resources further. These recent non-invasive scans will help take the guess work out of where to start.

Dr. Leslie also graciously allowed the team to place his 200 MHz GPR antenna in a rigged up catamaran made up of two kayaks connected by a wooden platform. This same sort of contraption was used by SEARCH and the team last summer to allow a search of the now-flooded swamp just north of Jamestown Rediscovery’s offices. With this lower frequency antenna the team is surveying the same areas as they did a few months ago, to compare and contrast last summer’s data with that from this higher-penetrating antenna. And on the river, near Statehouse Ridge (where the Archaearium now sits), Staff Archaeologists Gabriel Brown and Natalie Reid ran a new underwater survey. A 350 MHz antenna with a GPS unit was set into a kayak, and the team paddled back and forth to collect radar data just offshore. Nearly 500 feet of land has been lost due to erosion here, and this kayak experiment was undertaken to see if GPR could locate surviving archaeological features underwater. Gabriel and Natalie also did a GPR survey in their kayak clear across the river to see if any useable data might be obtained at various depths. Now that the surveys are complete, the data processing and analysis has begun. Stay tuned to future dig updates for the results.

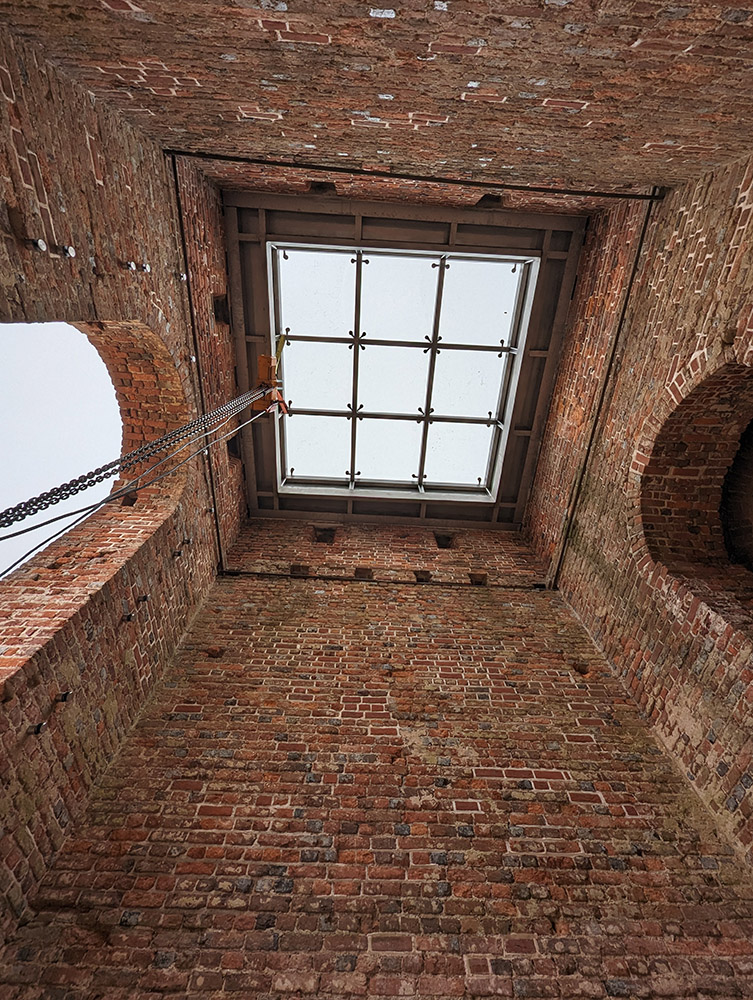

All nine glass roof panels are now installed in the 1680s Church Tower. The finishing touches are underway on the roof, the Church’s first in over 200 years. The roof will protect the Church’s interior, built with lower-fired bricks that were never meant to be exposed to the elements. A metal gutter and downspout has been installed, diverting water away from the historic structure. Work is also progressing on the Tower’s interior, where a portion of the floor will be made of glass to allow visitors to view the foundations of the 1617 church under their feet. The archaeological team worked hand-in-hand with the craftsmen installing the floor, building a wooden barrier to protect the archaeological resources during the concrete pour for the floor’s footing. They also did some last-minute archaeology to the channels that will hold the footings to ensure a precise fit. Finally, the Tower’s new “front door,” a glass portal designed to keep the elements out but maintain the Tower’s iconic facade, is nearing completion. Jamie May, Archaeologist and Director of the Voorhees Archaearium Museum, is producing signage that will inform visitors about the various archaeological and historic resources on display inside. The whole project will be completed in April.

Curatorial staff have finished cataloging all of the artifacts excavated from the Governor’s Well! A total of 2700 artifacts were found in the well feature. Bricks were by far the most common finds, but stones, organics like leather and rope, botanical material, Native ceramics and lithics, and metals were also plentiful in the well feature.

When analyzing many of the iron artifacts discovered in the Governor’s Well last September, the conservation team noticed a thin black slick covering many of them. A strong smell of sulfur also exuded from the artifacts. The conservators wanted to know what was causing these conditions in case they were signs of a situation that could be adverse to the artifacts’ well-being. Their research pointed to the presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria, “breathing in” sulfates in the well water and “breathing out” hydrogen sulfide as part of their respiratory processes. Hydrogen sulfide smells like rotten eggs and is corrosive to iron. Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins noted that the black slick — being the microbial mass itself — was easily removed with a shower of water. In his research, Chris discovered that the treatment for removing the bacteria was the same as what they were already using to remove chlorides from iron — submerging them in a sodium hydroxide bath. Removing chlorides from iron helps prevent oxidation (rust), so they were now killing two birds with one stone. The artifacts will remain in their sodium hydroxide baths for several weeks, their progress closely monitored by the conservation team. To learn more about the rapier and the challenges involved in its conservation, read the blog post “All Well and Good.”

Artifacts excavated from the interior of the Church Tower last month are now being cleaned and stabilized in the lab, and some exciting finds are being made. A large sherd of London post-medieval redware, excavated from the fort’s eastern palisade trench inside the Church Tower mends to a large jar in the collection! The jar’s other pieces were found in the fort’s first well, Pit 3, and the west bulwark trench, all early contexts in the fort’s history. Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins has completed conservation of the small complete glass bottle found in the eastern palisade trench inside the Church Tower. The bottle, standing a bit over two inches high, is a rare find as there are very few intact glass or ceramic vessels in the collection. Senior

Curator Leah Stricker and the volunteer team continue their sorting of artifacts found in the flotation samples from Pit 1 and Pit 3. The volunteers have been focusing on the heavy fraction from Pit 1 and have found a lot of small glass cullet, perhaps evidence of glassmaking nearby. They also found a hickory nut and a small glass bead. Leah has been finding a multitude of seeds during her sorts of the Pit 3 material.

Work on the olive jar reference collection continues by Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens. She is inventorying them, organizing them by context, and keeping an eye out for any that might mend together. These jars were used to carry a variety of food and drink, including olives, wine, chickpeas, and beans.

Senior Curator Merry Outlaw presented her research on Chinese porcelain excavated at Jamestown at “From the Ground Up,” a ceramics conference jointly sponsored by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, and held at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. The presence of Chinese porcelain at Jamestown, despite its scarcity in contemporary English archaeological sites, suggests intriguing connections between the Virginia colony and the broader world of international trade and conflict during the early 17th century. The fact that porcelain was an expensive status symbol in England underscores its significance at Jamestown. Some may have been brought by gentleman soldiers who acquired it when they fought with the Dutch in the Netherlands against the Spanish in the Eighty Years’ War. Two early Virginia adventurers, Captain Christopher Newport and Sir Thomas Dale, later traveled to Asia, where they both contracted illnesses and died. Ironically, Dale was sent to Southeast Asia to fight the aggressive Dutch. Outlaw’s forthcoming book promises to provide a comprehensive examination of Jamestown’s collection of Chinese porcelain, placing it within its broader historical context.

related images

- Some geese join the team during the GPR survey of the Pitch and Tar Swamp. (L-R) Director of Archaeology David Givens, Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid, Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown, Dr. David Leslie of TerraSearch Geophysical.

- A GPR survey of a portion of the Pitch and Tar Swamp in search of archaeological features. (L-R) Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown, Dr. David Leslie of TerraSearch Geophysical, Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid.

- Cole Peterson, Geophysical Specialist at Heritage Consultants, lays out a grid for a magnetometry study of Jamestown’s “Smithfield” where Captain John Smith led military drills of the colonists.

- Staff Archaeologists Gabriel Brown and Natalie Reid conduct a GPR survey of a portion of the James River.

- Contractors working on the Church Tower’s glass roof

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford excavates the area where the concrete footings for the glass floor will be installed.

- The archaeological team and contractors from Daniel and Company lower the base of the protective barrier that will shield archaeological resources during the concrete pour of the glass floor footings.

- The wooden case is installed to protect the 1617 church foundations during the concrete pour for the glass floor.

- Contractors from Daniel and Company pour concrete for the glass floor footings.

- A burnished brick found during the archaeological excavations inside the Church Tower.

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis explains the context of the dig adjacent to the ticketing tent to some visitors.

- The glass bottle found in the eastern palisade trench inside the Church Tower after conservation.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid holds the glass bottle she found in the eastern palisade trench inside the Church Tower.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker holds some of the hickory nut pieces found in Pit 1.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker holds some of the glass fragments found in Pit 1.

- Curatorial Assistant Lauren Stephens holds a sherd of a Spanish olive jar found at Jamestown. A bubble manufacturing flaw is evident.