All efforts in the field are focused on a brick-lined well just to the northwest of James Fort’s north bulwark. Found unexpectedly while following the trail of an early-17th-century ditch, it’s similar in appearance to another well found to the west of the fort that dates to the 1610s. Its proximity to the home of Samuel Argall, Deputy Governor of Virginia from 1617 to 1619, suggests it may be associated with that property. Many from the archaeological, curatorial, and conservation teams attended the Society for Historical Archaeology conference in Lisbon, Portugal this month. The team gave presentations on a variety of topics ranging including the latest exhibits in the Archaearium to Ming Porcelain and book hardware artifacts to Jamestown in the context of an English outpost in a Virginia Indian chiefdom. In the Vault, dozens of artifacts are being processed including several bricks bearing the footprints of animals. In the lab, plaster from the collapsed church tower burned during Bacon’s Rebellion is being conserved. The team is analyzing the bone-handled knife collection with an eye towards formulating the best long-term conservation strategy while simultaneously setting up a bone handle reference collection.

The area where the well was discovered is very complicated archaeologically as it contains a ditch from the earliest years of the fort as well as the moat from Confederate Fort Pocahontas (1861). Even accounting for that, the team didn’t quite know what to make of the soil layers they found as they progressed downwards. That is until the tell-tale shape of a circular course of bricks was discovered. They had stumbled upon a well. The confusing layer structure was further clouded by a third prominent feature thrown into the mix of the fort-period ditch and Confederate moat — the well’s builder’s trench. The builder’s trench is the larger hole dug around the well shaft so that its brick walls can be laid. Initially just half of the well was exposed, but this month the team excavated the layers above the other side, allowing the full circle to be daylighted. The construction of Fort Pocahontas in 1861 destroyed much of the higher layers of the well and a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) scan indicates there’s only about seven feet to go before the team hits the bottom. In addition to removing soil from the Confederate fort, they’ve also had to remove landscaping fill from several time periods, from the late 19th century to the early 21st. Also, dozens of thin layers of soil are visible from where they settled, brought down the Confederate earthwork by rain after the fort’s construction in 1861 until landscaping efforts covered them in the late 1890s. The archaeologists will be building a structure to allow the visiting public to view the excavations of the well in the months ahead. Wells are exciting features at Jamestown because they have historically been full of artifacts. The colonists used them as trash pits once their water soured and so all manner of artifacts have been found in their depths. Additionally, organic material can survive below the water line as the aerobic bacteria that typically consumes things such as leather or seeds can’t reach it. The next few months should be exciting ones for the team as well as visitors.

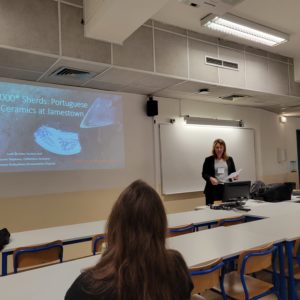

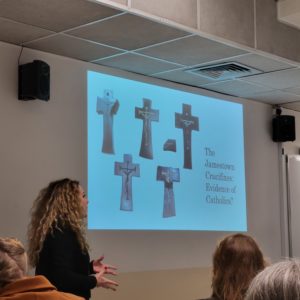

Jamestown was well represented at the Society for Historical Archaeology conference, with several papers focused on the site and its significance to the seventeenth century global trading network. Janene Johnston, Assistant Curator, coordinated a day-long symposium bringing together 18 papers from both staff and collaborators entitled “Opening the Vault: What Collections Can Say About Jamestown’s Global Trade Network.” Additionally, a presentation given by Director of Archaeology Dave Givens and co-authored by several members of the team entitled “Jamestown: An English Fort in the Land of Tsenacommacah” was part of a symposium discussing “Colonial Forts in Comparative, Global, and Contemporary Perspective.” Janene has written a blog entry summarizing some of the Jamestown-related presentations, which can be read here.

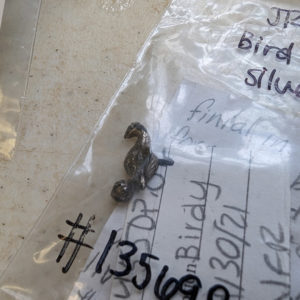

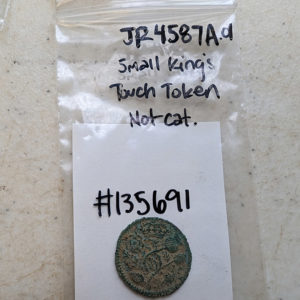

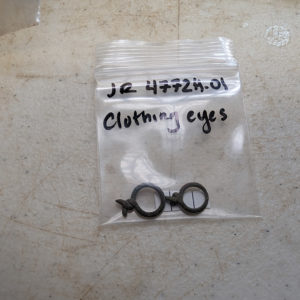

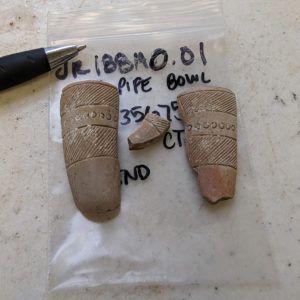

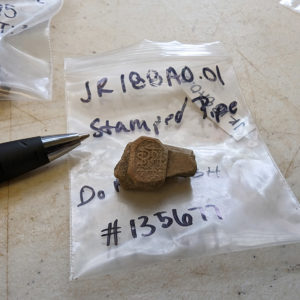

The curatorial team has been busy in the Vault and has been helped by some of the archaeologists when it’s raining or been too cold to conduct excavations. Lauren Stephens, Collections Assistant, is gathering architectural material in the collections for proper cataloging in the database and preparation for the reference collection. With help from the archaeologists searching through the archives on the second floor, she has consolidated bricks, mortar, and other building materials into a few adjacent drawers. Among the highlights are a collection of bricks touched by animals before they were fired centuries ago. Indentions from human fingers are on one brick, others bear the footprints of dogs. Pig and raccoon footprints are also represented in the brick collection. On one brick there is the footprint of a goose, a trace of an animal that frequents Jamestown to this day. Other members of the curatorial team have been gathering “featured artifacts,” those that are given priority for conservation or cataloging. Some of those in process this month include decorative pipe bowls, a thimble, Virginia Indian projectile points, a clay marble, a silver bird finial, and a King’s Touch Token (more info).

Next door in the lab, Dan Gamble, Senior Archaeological Conservator, is busy conserving plaster found in the shadow of the 1680s church tower. Thought to be part of the previous church tower that collapsed when it was put to the torch by Nathaniel Bacon’s rebels on September 19, 1676, the artifact is a rare example of an object in the Jamestown collection that can be tied to a single day in history. Dan is carefully removing the soil surrounding the plaster. His plan is to complete conservation on one side, cover it in plastic, and then create a plaster cast so that he can repeat the process on the other side. It’s a slow and painstaking process similar to many others Dan has completed in his many years as a conservator.

Dozens of bone-handled knives are being analyzed and conserved by Archaeological Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins. The knives present a challenge to the team in that the tang embedded in the bone handle is iron. Iron corrosion is more voluminous than the core metal. Therefore, as the iron corrodes, the corrosion will expand while putting pressure on the bone handle. If not acted upon immediately, this pressure will force the handle to crack, split and eventually fall apart completely. Artifacts like these — those that are comprised of multiple materials — are difficult to conserve because a treatment that may be effective for one material may not be effective or might even be harmful to the other. This is perhaps best illustrated in the example of the conservation of the Roman lock pistol found in the fort’s second well in 2006. The pistol was made of three primary materials — wood, copper-alloy, and iron. Chris ultimately decided to disassemble the pistol to treat each material separately. For these knives that is one line of reasoning — removing the blade from the handle and treating the iron to prevent further corrosion. But the blade’s tang is inside the handle and in some instances it cannot be removed without causing irreparable harm to the handle. In these cases the best option may be to limit further corrosion through careful control of their environment’s temperature and humidity.

dig deeper

related images

- The archaeological team at the well excavations

- Digging at the well. James Fort’s north bulwark can be seen at right.

- Removing the fill above the southern side of the well

- Archaeologists Hannah Barch, Natalie Reid, and Anna Shackelford excavate the soil over the well to expose the well ring bricks.

- A time capsule of nearly 40 years of wash layers. From 1861 when Fort Pocahontas was built until landscaping fill was placed over it in the late 1890s, rain eroded bits of soil down the Confederate earthworks into the moat. These thin layers are the result.

- A lead shot found while excavating the area around the well

- An English pipe bowl found close to the well

- Curator Leah Stricker gives a presentation on Portuguese ceramics found at Jamestown at the SHA conference.

- Gemologist Sarah Steele gives a presentation on jet crucifixes of Jamestown.

- Some of the Virginia Indian projectile points being processed in the Vault.

- A silver bird finial. The bird is sitting on a round base.

- A King’s Touch Token

- A clay marble

- Clothing eyes

- A copper alloy thimble

- A decorative pipe bowl made from Virginia clay.

- An octagonal pipe heel stamped with a Quatre de Chiffre mark

- A decorative pipe bowl made from Virginia clay

- Some of the bone-handled knives in the collection. The piece at center retains a large section of its blade.

- Using a microscope to aid in the conservation of a bone-handled knife.

- A bone-handled knife

- Bone-handled knives

- A bone-handled knife

- A bone-handled knife