The forensic work done on the bones of “Jane” in 2013 has led to a re-evaluation of previous finds by the Jamestown Rediscovery team.

The forensic work done on the bones of “Jane” in 2013 has led to a re-evaluation of previous finds by the Jamestown Rediscovery team.

That work was discussed in January at the Society for Historical Archaeology’s 47th conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology in Quebec. Senior Staff Archaeologist Jamie May and Kari Bruwelheide, a Smithsonian Institution specialist in skeletal biology, described how disarticulated human bones have been discovered within sealed, fort-period contexts that are not graves. The fill layers of a bulwark trench, the second well, and the cellar of an early work building all yielded partial human crania in the years of archaeological work before Jane was found. But unlike Jane, none of these individuals showed evidence of being processed for cannibalism.

The Jamestown settlers suffered high death rates from the very start, and their burials across the 22.5-acre Preservation Virginia property are prolific. As waves of settlement increased and land usage changed, early graves were subject to disturbance. Burials cut and overlay other burials, as did ditches, pits, roads, buildings, and the 1861 Confederate earthwork fort. Finding fragmented and redeposited human remains is a fairly frequent occurrence in these disturbed areas of the James Fort site. Less frequently though, significant elements of human remains have been found in sealed deposits dating to the James Fort period (ca. 1607-1624).

For example, a portion of a human skull was unearthed in 2003 from a trench that extended along the exterior palisade from the west corner bulwark of the fort.

According to colonist Ralph Hamor, the west bulwark was strengthened under Governor Gates between 1611 and 1614. It appears the bulwark trench was extended at that time, incorporating a possible sawpit outside the west palisade, and that it was filled within the next few years.

The bulwark trench fill was rich in artifacts, such as a surgical “scraper” and a piece of sulfur, which had many medical uses. In an upper fill layer, a fragment from the back of a human skull was recovered. Forensic analysis indicated it was from a European male, aged 30-44 years.

This individual sustained at least two mortal blows to his head. One impact involved the lower left parietal and occipital bones behind the ear. Radiating fractures extended from this penetrating defect, indicating forceful impact by a heavy, blunt-edged object. The location of the blow was low on the head, suggesting that the individual may have been wearing a helmet. A second radiating fracture indicated another injury involving the right half of the skull.

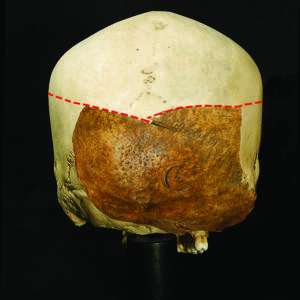

After the individual’s death, the entire section of bone was removed from the rest of the skull by a surgical dissection that involved sawing through the back area, as performed in an autopsy. Analysis revealed that the skull was positioned and sawn from several angles, with a saw blade measuring approximately 0.7 mm.

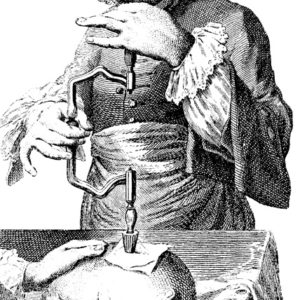

More remarkably, there are signs of trephination—a surgical procedure performed in response to head injuries, whereby surgeons removed a plug of bone from the skull to prevent a buildup of fluid that could cause pressure on the brain. Surgeons could also use the cavity to remove broken pieces of skull.

There is evidence of two failed attempts with a circular trephining saw, one attempt in the midline just above the protuberance (bony bump), and another attempt evidenced by two slightly deeper, overlapping circles about 2 cm away. The attempts were made at or about the time of death, and since they do not go all the way through, it appears both efforts were aborted. Since this is the thickest part of the skull and not in direct association with the fractures, it was not a good choice for a successful operation. This indicates the operation may have been the work of a very inexperienced surgeon.

related images

- Close-up view of trephination scars

- Early illustration of trephining

- Trephined skull fragment excavated at Jamestown

- West bulwark ditch and saw pit