In the wintertime, with fieldwork temporarily at a halt, conservation efforts in the laboratory are aided by the addition of staff archaeologist Don Warmke who has been assisting the conservators stabilize iron artifacts.

In the wintertime, with fieldwork temporarily at a halt, conservation efforts in the laboratory are aided by the addition of staff archaeologist Don Warmke who has been assisting the conservators stabilize iron artifacts.

“We’re a military site, so we have a lot of iron—their tools and their armor and their weapons,” said Michael Lavin, senior conservator for the Jamestown Rediscovery Project. “To tell their story, we have to conserve the iron.”

Many of the lumps of rust come into the Rediscovery Center laboratory looking like pieces of fried chicken. The iron artifacts are not washed because chlorinated tap water mixing with oxygen and water vapor in the air will cause MORE rust.

“We definitely do not want to introduce any more chlorides to an already-rusting artifact,” Lavin said.

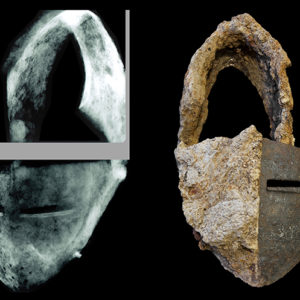

So after the rust-covered artifact is cataloged and assigned a unique identification number, it gets an x-ray.

Senior Archaeologist Danny Schmidt said, “That’s one of the things we wrestle with: we can’t necessarily identify an object in the field because more often than not so much rust has accumulated on the object that it is no longer identifiable.”

Conservator Dan Gamble does most of the x-ray work. “The x-ray will show us what the metal is like underneath the rust and tell us how we will treat it,” Gamble said.

The project takes an average of 350 x-rays a year, and there were almost 400 in 2012. The conservators used to take artifacts to a NASA Langley lab in Hampton or to Colonial Williamsburg’s lab for this non-destructive diagnostic tool. Then Jamestown Rediscovery was awarded a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services that delivered a digital x-ray machine to the project’s own lab in 2009. Since then the Jamestown team has taken x-rays of more than 2,000 non-nail iron objects from the James Fort-period features. Having the equipment at hand allows for a richer database about many artifacts.

“Digital x-ray allows us to get a sneak peak through the artifact, helping with identification, conservation treatment methods, and what we want to actually do with the artifact,” Lavin said.

Sometimes the x-ray can even show a “maker’s mark” on an iron tool, which helps date and locate the origin of the tool. On the x-ray picture, the areas that show up white are more dense, the black areas are less dense.

If the object is found to consist of solid metal with no weak spots, it is put into a tub of water with three percent sodium carbonate for the process of electrolytic reduction. This process reverses the flow of electrons, causing the rust to drop off. Staff Archaeologist Don Warmke manages this process for objects such as cannonballs, hoe blades, cooking pots, axes, or other heavy tools, which tend to survive relatively intact.

Lavin said, “We use this for anything that has enough iron that we want to make sure we don’t lose any information by popping off the rust–which is kind of rare for us, to find things that have enough core iron in them after 400 years.”

The time in the solution varies for each object, but objects are in the electrolysis tank for at least a month.

If the x-rays show there’s not enough iron beneath the rust, the artifact is air abraded with a very fine aluminum oxide powder. An air abrader is a hand-held tool similar in form to a pencil that propels a fine powder at an object through the use of pressurized air. Though time-consuming, the tool has a fine tip and enables a high level of precision, perfect for objects that can’t withstand a brute-force approach to rust removal.

Gamble and Warmke do most of the air abrasion now, but Lavin has been doing it for the archaeological project for 18 years and Gamble for 13. Warmke has been training on the air abrasion equipment for three years and last month worked on cleaning some jack plates and matchlock lockplates. The lockplates can be cleaned in a day or two; sword hilts take three to four days.

“It’s like a mini-sandblaster, to blow away the rust,” Lavin said. “Air abrasion takes a lot of skill because you don’t want to take away any information from the artifact. It’s like the doctor’s oath. The first rule is: do no harm.”

After objects are done with the electrolysis or the abrasion process, they spend three or four months soaking in a de-ionized solution with less than four parts per million of soluble chlorides, which leaches even more chlorides out of the artifacts.

Then there is time in a vacuum chamber with silica gel to dry out the artifact. After all this cleaning and stabilization, a conservator takes the flash rust off the object with some more air abrasion and coats the artifact with acrylic to protect it before going on display in the Archaearium or into storage in the dry room of the Vault at the Rediscovery Center.

“Visitors see the archaeological process in the field but probably don’t realize all the effort that goes on behind the scenes to enable the continued research on the archaeological finds,” said the project’s Senior Archaeological Curator, Bly Straube. “Every object on view in the Archaearium has hours of work behind it devoted to both giving it a voice and preserving it for the future.”

related images

- Cellar site where the helmet came from

- Jamestown Rediscovery Archaeologist Mary Anna Richardson excavating

- Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Richardson excavating the close helmet

- Helmet during conservation

- Senior Conservator Michael Lavin conserving close helmet recovered from an early James Fort cellar

- X-ray of an iron close helmet

- Half-conserved helmet