The sturgeon bones layered across the floor of the L-shaped cellar illuminate how important the river was as a source of food for early James Fort colonists.

The sturgeon bones layered across the floor of the L-shaped cellar illuminate how important the river was as a source of food for early James Fort colonists.

Much has been written about Captain John Smith’s negotiations with the Powhatan Indians for corn, but we know that in 1608-09 the colonists were also working with sturgeon.

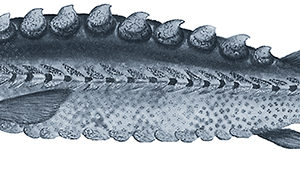

Sturgeon have long bodies, no scales, and can grow to 12 feet in length. They are bottom-feeders in the rivers and coastline of North America, spawning in fresh water and then feeding in the brackish waters of estuaries.

Smith mentions sturgeon early in the colony’s story: “From May to September [1607], those that escaped lived upon sturgeon and sea crabs” but by the fall “was all our provision spent, the sturgeon gone, all help abandoned. . .”

Virginia Commonwealth University ichthyologist Matthew Balazik said spring run adult sturgeon usually enter James River in late March and leave by June and some fall spawning Atlantic sturgeon can be in the river from late July to early October. He has studied sturgeon remains from early Jamestown and published a report in 2010 showing sturgeon from that era grew more slowly than sturgeon today, which may reflect today’s lower population density or higher water temperatures.

Balazik visited the L-shaped cellar December 14 and was excited to see the evidence of sturgeon from which he could estimate that they were between five and eight feet long. The sturgeon pieces are scattered on the floor near one of two brick ovens in the L-shaped cellar.

Smith wrote that in early 1609, “We had more sturgeon than could be devoured by dog and man, of which the industrious by drying and pounding, mingled with caviar, sorrel, and other wholesome herbs, would make bread and good meat. Others would gather as much tockwhogh roots in a day as would make them bread a week, so that those wild fruits and what we caught we lived very well in regard of such a diet.”

But when Samuel Argall arrived with two supply ships in July, he found many of the colonists hungry because they refused to sow their own crops. Many settlers had been “dispersed in the savages towns, living upon their alms for an ounce of copper a day,” and even Smith admitted that “our necessities was such as enforced us to take” the fish, wine, and biscuits onboard Argall’s ships.

Part of Argall’s mission was to find out how good the fishing was in the waters off Virginia’s coast. Fish were a valuable commodity to the English: their ships had been fishing off Newfoundland for decades before Jamestown was founded.

In the cellar, the Jamestown colonists may have been processing sturgeon for the home market. Sturgeons and whales are actually royal fish in England. According to a law enacted by Edward II (who reigned 1307 to 1327) they are the personal property of the monarch when caught and brought to English shores.

Argall returned to England and reported favorably. “[F]or fishing proved so plentiful, especially of sturgeon, of which sort he could have loaded many ships if he had had some man of skill to pickle and prepare it for keeping, whereof he brought sufficient testimony both of the flesh and caviary, that no discreet man will question the truth of it.”

That fall, the Jamestown colonists did not take care of the seasonal nature of the sturgeon food supply. A mysterious gunpowder explosion sent Smith back to England in November 1609, and the arguing factions he left behind in James Fort did not prepare well for the coming winter.

Colony Secretary William Strachey wrote of this time, “There is a great store of fish in the river, especially of sturgeon, but our men provided no more of them than for present necessity, not barreling up any store against that season the sturgeon returned to the sea. And not to dissemble their folly, they suffered 14 nets (which was all they had) to rot and spoil which by orderly drying and mending might have been preserved. But being lost, all help of fishing perished.”

That winter of 1609-10 became known as “The Starving Time.” Almost three-fourths of the colonists inside the fort died, and that spring the colony came within a few days of being abandoned. It appears that by June of 1610 the L-shaped cellar now being explored by the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists was no longer in use.

The cellar is 25 feet long and aligns with James Fort’s first well, which sits 10 feet away to the west and at the same angle.

related images

- Cross section of a sturgeon spine

- VCU ichthyologist Matthew Balazik with a live sturgeon

- View from above of Structure 191’s eastern brick oven and sturgeon scutes

- Watercolor of a Sturgeon by John White