Standing by the James River, Dr. James Horn, president of Jamestown Rediscovery, told a film crew from the National Trust for Historic Preservation that “it would be an act little short of vandalism to erect 300-foot towers across the river.”

“Jamestown is one of the most important historic sites in the country, a cultural resource of incalculable value,” he said. “What you see from the island and adjoining parkway is pretty much what the river looked like 400 years ago. You are looking at a viewshed that Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and the first African arrivals in 1619 would have seen.”

Indian peoples lived along the James River for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. In the 16th century Spanish mariners explored the river, and early in the following century its deep channel led the English to establish their first permanent North American settlement on Jamestown Island. The river was a vital conduit of trade from Virginia to England; convoys of ships brought settlers and goods to the colony and shipped tobacco back to London and other major ports. The British army and navy invaded Virginia along the James River towards the end of the American Revolution, and two armies, blue and gray, confronted each other along its banks during the Civil War.

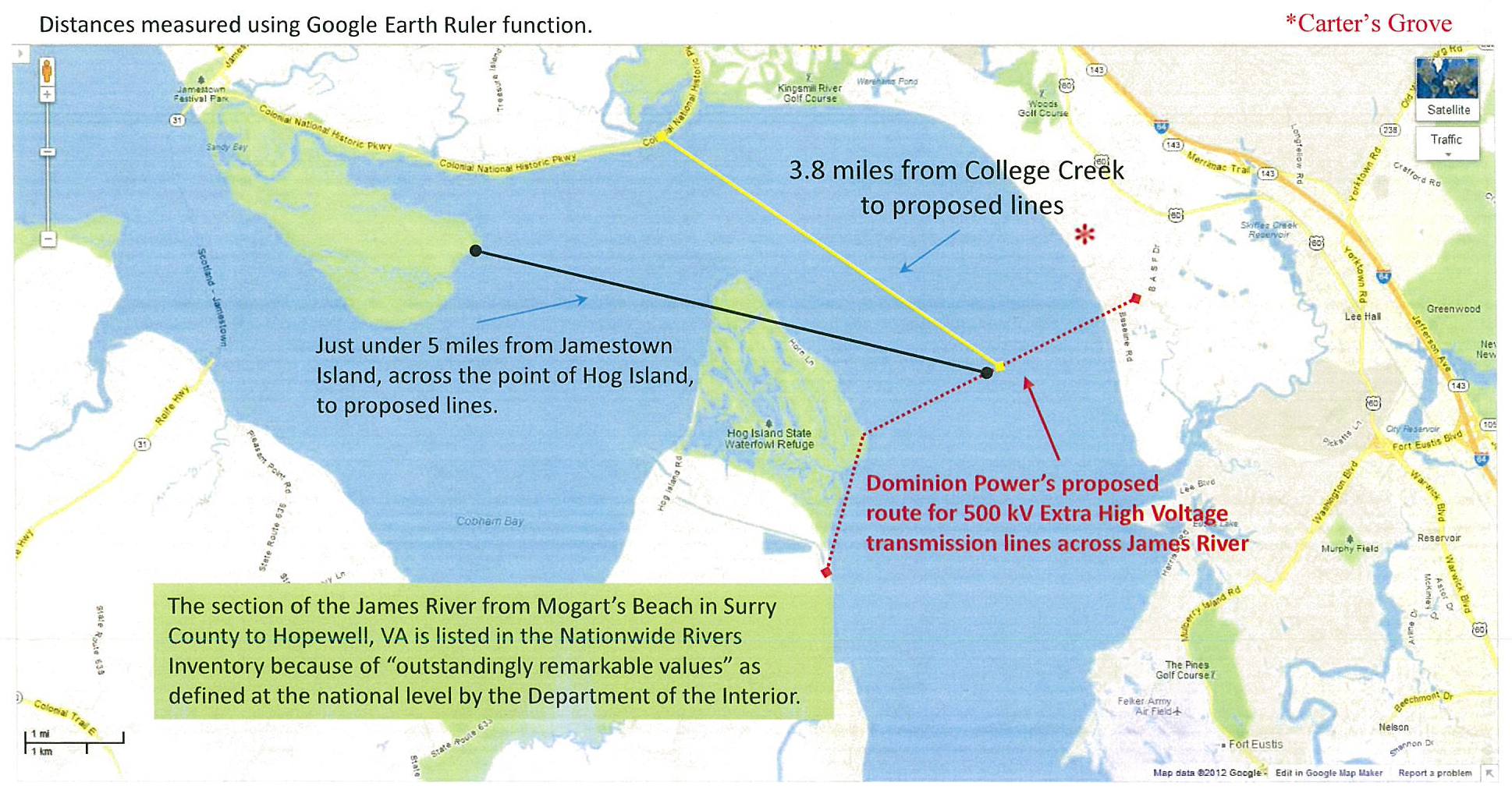

Dominion Virginia Power is pursuing regulatory permission for a transmission line across the James that would dramatically alter the landscape, disrupt wildlife, and jeopardize the river’s many recreational uses. Dominion’s plan would put 17 towers—some as tall as the Statue of Liberty—across the river from Hog Island to James City County, just south of the Carter’s Grove historic plantation.

Dr. William M. Kelso, director of archaeological research at Jamestown Rediscovery, excavated at Carter’s Grove and other early settlement sites along the river before Jamestown Rediscovery’s work began on the island in 1994.

Kelso said of the tower plan, “What is the price of that piece of river? It’s priceless. The James River is the heritage of the people of Virginia. Why should a private company be allowed to spoil it? There’s got to be an alternative. Why not put the lines under the river bed for example?”

Kelso noted that the towers, though not visible from the James Fort site on the west end of the Island, would mar the view of visitors on their way to the island. The line would stand about 3.75 miles from the Colonial Parkway section that runs beside the river. It would stand about 5 miles from the beach at Black Point on the eastern end of Jamestown Island. “The towers would destroy that view,” Kelso said.

At hearings before the State Corporation Commission, Dominion’s plan was opposed by James City County, Save the James Alliance, and the James River Association. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the College of William and Mary, and Preservation Virginia joined in opposition. But the commission approved Dominion’s plan in November 2013.

The commission’s decision was appealed, and on April 16, 2015, the Virginia Supreme Court ruled the commission erred in part because a planned switching station in James City County—a station which Dominion has said is fundamental to the project—must win county zoning approval. Beyond a county review, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers must also approve the project and has not decided yet on how detailed its review will be.

A “Down to the Wire” coalition has formed to gather signatures against the proposal. The coalition includes Preservation Virginia (which owns the James Fort site), the Chesapeake Conservancy, the Garden Club of Virginia, the James River Association, Save the James Alliance, Scenic Virginia, the National Parks Conservation Association, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The film crew that visited Jamestown in mid-April plans to make public in May several videos about the history along the James. There are already four “Down to the Wire” videos on the National Trust’s YouTube channel. A petition has gathered more than 21,000 signatures and is taking more here.

“We are focused on telling as much of the comprehensive history of the James River as we can so it will help people understand what Dominion’s plan puts at risk,” said David Weible, a content specialist for the National Trust film crew. “We are trying to bring the story of this river to the people who cannot visit the river themselves.”

The coalition is also running newspaper ads and will bring its bright yellow van to the events on the island on Jamestown Day, May 9, to gather more signatures and discuss the proposal.

“Preservation isn’t about impeding progress,” Horn told the film crew. “We are saying that you don’t have to put the transmission lines right here.”

The National Trust discusses those alternatives on its website section devoted to the Down to the Wire effort.

Kelso has lived in a cottage on Jamestown Island for 22 years. He spoke on camera about his concern that the transmission lines would also be a tipping point that would lead to more construction on the James—such as a highway bridge just west of the island that is often discussed as a replacement for the ferries there.

“The context of Jamestown is the river,” he told the film crew.

Historic Jamestowne is jointly administered by the National Park Service and Jamestown Rediscovery (on behalf of Preservation Virginia) and preserves the original site of the first permanent English settlement in the New World. Guests share the moment of discovery with archaeologists and witness archaeology in action at the 1607 James Fort excavation April-October; learn about the Jamestown Rediscovery excavation at the Nathalie P. and Alan M. Voorhees Archaearium, the site’s archaeology museum; tour the original 17th-century church tower and reconstructed 17th-century Jamestown Memorial Church; and take a walking tour with a Park Ranger through the New Towne area along the scenic James River. Guests can also enjoy lunch or a snack by the James River at the Dale House Café.

Preservation Virginia, a private nonprofit organization and statewide historic preservation leader founded in 1889, is dedicated to perpetuating and revitalizing Virginia’s cultural, architectural and historic heritage thereby ensuring that historic places are integral parts of the lives of present and future generations.