William Strachey, secretary of the Virginia colony, described Jamestown’s church as such in a letter to an acquaintance in England in 1610. The Jamestown Rediscovery team has found six postholes, unusually deep, unusually large in diameter, and most interestingly, they appear to fit perfectly into Strachey’s description of what was Jamestown’s first substantial church, built in 1608 and being the probable location of the wedding of John Rolfe and Pocahontas. There is a sense of cautious optimism among the archaeologists that they have indeed found the spiritual hub of the colony.

The first Anglican services held at Jamestown were not held in a church at all, but rather (according to Captain John Smith) “under an awning (which was an old saile),” and tied between trees so as to be held aloft. Then, a makeshift building served as a church, described by Captain Smith as “a homely thing like a barn set on crachetts, covered with rafts, sedge and earth.” This burned in January 1608 and was soon replaced by the church that Strachey describes in 1610, though at that point it had fallen into a state of disrepair. Upon taking governorship of Virginia that same year, Lord De La Warr

…hath given order for the repairing of it, and at this instant many hands are about it. It is in length three-score foot, in breadth twenty-four, and shall have a chancel in it of cedar and a communion table of the black walnut, and all the pews of cedar, with fair broad windows to shut and open, as the weather shall occasion, of the same wood, a pulpit of the same, with a front hewn hollow, like a canoe, with two bells at the west end. It is so cast as it be very light within, and the lord governor and captain general doth cause it to be kept passing sweet and trimmed up with divers flowers, with a sexton belonging to it. And in it every Sunday we have sermons twice a day, and every Thursday a sermon, having true preachers, which take their weekly turns; and every morning, at the ringing of a bell about ten of the clock, each man addresseth himself to prayers, and so at four of the clock before supper.

Every Sunday, when the lord governor and captain general goeth to church, he is accompanied with all the councilors, captains, other officers, and all the gentlemen, and with a guard of halberdiers in His Lordship’s livery, fair red cloaks, to the number of fifty, both on each side and behind him; and, being in the church, His Lordship hath his seat in the choir, in a green velvet chair, with a cloth, with a velvet cushion spread on a table before him on which he kneeleth; and on each side sit the council, captains, and officers, each in their place; and when he returneth home again he is waited on to his house in the same manner. —William Strachey, 1610

The third church, ordered built in 1617 by Captain Samuel Argall, was made out of wood but had a cobblestone foundation. Its remains can be seen under glass panels inside the Jamestown Memorial Church. Built in 1907, the Jamestown Memorial Church sits adjacent to the still-standing 17th-century church tower.

The postholes found this month that are possibly part of the second church struck the archaeologists as strikingly deep and unusually wide. This suggested that the posts supported a very substantial building. After the first was found, two more were found 12 feet apart in a straight line to the southwest (for a total of 24 feet, matching Strachey’s width observation), similarly deep and wide. A fourth hole, found twelve feet to the northwest of the first, makes a right angle with the line formed by the first three, forming one of the building’s corners. The length of the church was described as “three-score foot” or sixty feet. Did the colonists put a posthole at five regular 12-foot intervals for a total of 60 feet? That is the hope of the Jamestown Rediscovery team. They have measured and placed markers where the other postholes should be if their theory were to hold true. Future excavation will determine if we have finally found James Fort’s church.

Seven graves, potentially from the fort period, have been found inside the east end of the building. If further archaeological evidence does prove this to be the church, then the east end would have housed the chancel and only colonists of high standing would have been buried there. There very well may be more burials within the church, further to the west. The presence of such graves may give us some idea where the colonists sat—and didn’t sit—during church services.

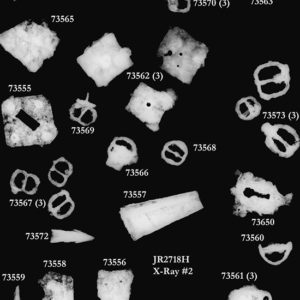

Jamestown Rediscovery conservators have been putting their x-ray machine to good use. Purchased in 2009 through a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the device has been invaluable in allowing the conservators to identify objects and approach their conservation in the best way possible. Four-hundred-year-old iron objects found during the excavations are often times unrecognizable. Centuries of oxidation can leave them as little more than amorphous chunks of rust. X-rays reveal the object behind the rust…what’s left of the original metal. This guides the conservation process because the team can use the x-rays to see where to be careful and where to be more aggressive during the rust-removal process.

Jamestown Rediscovery conservators have been putting their x-ray machine to good use. Purchased in 2009 through a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the device has been invaluable in allowing the conservators to identify objects and approach their conservation in the best way possible. Four-hundred-year-old iron objects found during the excavations are often times unrecognizable. Centuries of oxidation can leave them as little more than amorphous chunks of rust. X-rays reveal the object behind the rust…what’s left of the original metal. This guides the conservation process because the team can use the x-rays to see where to be careful and where to be more aggressive during the rust-removal process.

Conservation is complete on several of the metal objects found in the fort’s first well, built in 1609 and excavated in 2009. After being brought into the lab and stabilized, the artifacts are x-rayed for both identification purposes and to give the conservators an idea of how best to remove the rust. Weak parts of the artifact—where the original metal has largely corroded away—aren’t as bright on the x-ray as the portions that are more intact. These parts must be treated gingerly, and in especially weak sections the rust cannot be removed completely as an oxidized shell is all that remains. Among the artifacts that have been conserved this week are a buckler strap, a copper-alloy chain, a crossbow bolt, a lock plate, a strap guide, and a keyhole escutcheon.

related images

- A conserved keyhole escutcheon found in the fort’s first well

- A conserved lockplate found in the fort’s first well

- A conserved strap guide found in the fort’s first well

- A x-ray of several iron objects found last year in the fort’s first well. The lock plate is labeled ‘73555,’ the crosbow bolt ‘73572’

- An aerial of the excavation area. The possible church postholes are labeled STR 188.

- Archaeologist Mary Anna Richardson stands in a late-seventeenth-century zigzag ditch that was probably used to contain livestock or mark property boundar

- Archaeologists and visitors mark the discovered postholes and probable locations of to-be-excavated postholes of the possible 1608 church.

- Copper chain x-ray. This chain was found in the fort’s first well.

- Part of a conserved buckler strap found in the fort’s first well

- The crossbow bolt after conservation

- Two of the copper chains after conservation