During April, archaeologists completed removal of all the trash layers filling the cellar at the northeast corner of the 1608 extension (Structure 193). Several interesting iron artifacts were revealed, including a chisel, pieces of armor, and a bandolier. The rusted bandolier cylinder exhibited a pseudomorph, or impression, of a small leaf that was tossed into the same trash layer over 400 years ago. As the leaf decayed, the iron bandolier began to oxidize, and the corrosion products retained the form of the leaf.

The most intriguing iron artifact found in April was about half of a circular-shaped grill from a wrought iron griddle. The circular outer rim, one curvy bar, and one straight bar were recovered, which would have been duplicated on the other half of the intact grill. Challenging to identify in the field because of heavy rust, digital x-rays in the Rediscovery lab determined that the metal was thin and flat. “An intact griddle would have stood on three short feet, and its long handle was used to push it into and pull it out of the fire,” explains curator Merry Outlaw. A ceramic frying pan discovered in James Fort’s First Well is the type of vessel that would have sat on this griddle for preparing food.

With all the trash layers removed from the cellar, the archaeologists have concentrated on defining, mapping, and photographing the architectural features visible on the cellar’s floor. Jamestown Rediscovery photographer Michael Lavin was called upon to capture some official overall record shots of the cellar at this phase. In his overall shots, one can see the postholes, stains for wood beams, and floor boards that show up in the cellar’s occupation level.

Several of the small posts identified along the edges of the cellar’s walls were cut back into the subsoil and cut through the cellar’s occupation layer. It is evident these postholes were dug after the building was already in use, and not when it was initially constructed. “When you examine the holes carved into the wall to accommodate these posts, you realize how similar in size most of the holes are to the width of the dozens of iron spade nosings we have recovered in James Fort’s early contexts. You can almost visualize a colonist in the cellar using his shovel to dig out a nook just big enough to fit a small post,” archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley noted. The postmold soil stains found along the walls ranged from 4” to 6” in diameter. It is unlikely that these posts supported the main structure above the cellar, but they would have been adequate to shore up floor joists used to support the floor above the cellar.

Excavations around the well shaft soil stain finally revealed the feature’s full limits as 5’ by 6’. Archaeologists Danny Schmidt and Bob Chartrand took elevations from the top of the well shaft and compared them to a spot of standing water in the nearby marsh for clues to how much deeper we will dig before hitting water. “Based on the level of the standing water in the marsh, we will excavate only 3 to 4 feet deeper until the ground is saturated,” according to Schmidt. If our past experience excavating the nearby wells is any indication, this prediction is likely accurate.

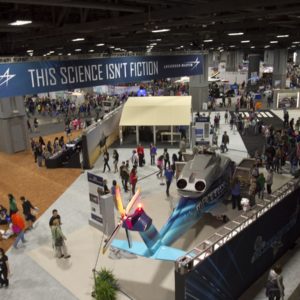

This month the Greater Williamsburg Chamber and Tourism Alliance asked the Jamestown Rediscovery team to represent Williamsburg at the 2016 USA Science and Engineering Festival, and the team gladly accepted the request. Held every two years, the Festival is advertised as the World’s Largest Family Science Fair. Rediscovery archaeologists, curators, conservators, and educators taught kids and their parents how we use science and technology to solve archaeological and historical mysteries and make new discoveries about Jamestown’s past.

Check out the dig update video, featuring our conservation team discussing the discovery and conservation of the wrought iron griddle.

related images

- Conservators Dan Gamble and Katy Corneli remove fill from around an iron object to remove it from the cellar.

- An iron chisel found in the cellar fill.

- A badly corroded iron bandolier with the psedomorph of a leaf on it.

- Portion of a circular wrought iron griddle with curvy and straight barb.

- Conservator Dan Gamble places the giddle in our x-ray machine.

- The x-ray of the griddle revealed a couple of detacted fragments and a few areas where the metal was weak.

- Curator Merry Outlaw holds an exarmple of a ceramic frying pan found in the Fort’s first well during excavations in 2009. This is the type of vessel that would have been placed on the griddle.

- The back of this North Devon gravel tempered frying pan from the John Smith well shows scorch marks from use.

- Overall record shot of the cellar taken looking slightly northwest.

- Record shot of the cellar showing its relationship to the 1608 extension.

- This long, thin soil stain on the cellar floor is believed to be evidence of a floorboard that fell down on to the cellar floor right before the cellar was filled. The board then rotted in place and left a cavity where it once sat and stained the soil around it a purple/gray color.

- Archaeologist Mary Anna R. Hartley points to one of the several postholes found that were cut into the cellar’s west subsoil wall.

- Note how square and flat the back of the cut into the wall is.

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand holds up a shark vertebra found in the cellar’s occupation layer. Much of the finds are food remains including this one.

- A copper Kruwinckel jetton, or counter found in the cellar.

- Willie Balderson as Anas Todkill with a NASA astronaut at the USA Science & Engineering Festival.

- Scene from the USA Science & Engineering Festival.