It’s kids camp month! The cellar excavation site, Vault, and lab came alive this month with the sights and sounds of our two annual kids camps. Both camps dug at an excavation site we’re currently calling “the cellar” because ground-penetrating radar (GPR) suggested the presence of a brick-lined cellar here. Trowel-in-ground excavations during this year’s field school seemed to lend credence to the GPR’s findings, daylighting several bricks in what may be the top layer of the cellar. The feature is on the property of John Howard, a tailor who purchased the land here in the 1690s. Whether the structure belonged to him or was from a different time period will hopefully be answered as the archaeologists progress deeper.

July was a HOT month and so the team covered the excavation area (and the kids) with shade-providing tent canopies. Water was always available and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid, manager of the kids camps, planned indoor activities for the afternoons when the temperatures reached their peaks. Each session of camp dug in two different pairs of squares, one on the north side of the cellar site, and the other on the west side. The archaeological team excavated the top modern landscaping layers prior to the start of the camps so that the kids could focus on the historic layers beneath. The campers spent much of their time playing in the dirt: shoveling it, troweling it, screening through it looking for artifacts, and then using wheelbarrows to take it away for backfilling when the excavations were done.

The kids excavated in the plowzones of each section, that is the depths at which farmers’ plows clawed into the earth churning up and mixing soil layers, both horizontally and vertically. Plowscars are visible as long thin lines of soil that are a different color than the surrounding earth, a symptom of the plow blade’s soil mixing. Our archaeologists find plowscars almost everywhere they dig, a testament to almost three centuries of farming on Jamestown Island. The kids found several different artifacts of note, ranging from thousands of years old to decades old. A largely intact projectile point, possibly an example of a Clagett type, could date to roughly 4000 to 3000 BCE, speaking to the thousands of years of use of Jamestown Island by Virginia Indians. Artifacts likely dating to the 17th century include a variety of ceramics such as delftware and Midlands purple as well as firearms-related items like lead sprue. Lead sprue is the waste from shot manufacture, the leftovers after the balls are clipped from the molded lead. A 20th-century find may interest numismatists. One of our campers found a silver (90% silver, 10% copper) Standing Liberty quarter, minted between 1916 and 1930. It is heavily used, wear wiping away many of the coin’s raised details including the date that was once below Liberty’s feet.

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) enables archaeologists to learn a lot about a site without digging so much as a single shovelful of dirt. The technology allows the team to find anomalies several feet under the soil, whether they be archaeological features or tree roots. It has become an indispensable tool to the Jamestown archaeologists, allowing them to focus on promising areas and save time in the process. Because of its importance to the modern archaeological process, the team gave the campers instruction on both the use of their GPR machines and the science behind them. The archaeologists let them do test surveys outside at various locations across the site and in the Church Tower where the west foundation of the 1617 church lies below the floor.

In the afternoons when the temperatures were at their highest, the campers headed inside the Jamestown Rediscovery Center where the archaeologists and collections staff had lessons planned for them. The collections staff created stations in the Vault (and in the air conditioning) where the campers were taught about specific artifact types. Faunal remains, ceramics, glass, and many other types of artifacts were included in the program. Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid asked the children which artifacts they were most interested in so the curators could incorporate those items into the lessons whenever possible.

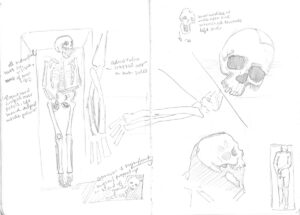

One of the inside exercises was the mending of broken reproduction ceramic vessels using the same methods and materials employed by our conservators and curators. The campers used painter’s tape to mend sherds together, a tool also used by our collections staff as a temporary adhesive. Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb, our resident expert illustrator, gave the campers a lesson on the importance and methods of archaeological illustration. She shared some of the techniques she uses to portray both archaeological features and artifacts whether she’s out in the field or in the lab.

As archaeology is often a study of the past by studying trash, the archaeologists brought in (sanitary) trash from their homes to drive home the point, with the kids studying the trash and sharing what it taught them about its owners. Each camper had one group of trash, and after examining it they tried to match it to its former owner on the archaeology team. As difficult as this was, they had the benefit of living in the same time and place as the archaeologists, making recognition of the trash much easier than 400 year old artifacts.

The kids also spent time in the Ed Shed, picking through tiny material from the John Smith Well (the fort’s first) looking for artifacts. Young eyes are required for this task, so the kids were well suited for this activity. Faunal remains such as fish scales and rodent bones as well as small beads and lead shot are typical finds in this assemblage. Associate Curator Emma Derry even found a small bone die while picking through this material last month.

Associate Curator Janene Johnston has continued to work on materials related to horses and arms (weaponry) in July, working on the reference collections for iron spurs and lead shot. Reference collections contain unique and representative examples of artifact types and are stored on the first floor of the Vault for easy access to staff and outside researchers. Once this collections management work is complete, a website page with information about the spurs and lead shot will be available so everyone can take a glimpse at the artifacts in the Jamestown collection. The iron spurs are housed in the “dry room” where temperature and humidity are tightly regulated to inhibit corrosion (AKA rust). The colonists wore spurs made of both iron and copper alloy, although there are many more iron spurs than copper alloy spurs in the Jamestown collection, likely due to iron being less expensive.

The lead shot reference collection contains not only bullets, but also items related to their production such as bullet molds and sprue. While round shot dominates the collection, several 19th-century Minié balls are also in the collection, some of which have been deformed either during loading (an overzealous rifleman smushed one of the bullets with a ramrod) or by impacting a target. Jamestown Island was occupied by both the Confederates and the Union at different points of the Civil War.

Janene is also picking through objects found in a midden near the Seawall in 2021. Her work is part of an effort to document the midden via written reports, part of which is an accounting of the artifacts found there. Her painstaking work has resulted in the discovery of many small artifacts, including 28 small glass “seed” (so called for their small size) beads. Picking in the Ed Shed this month also led to an exciting discovery: a faceted gemstone, likely quartz, and probably belonging to a finger ring. The gemstone was part of a collection of small objects found in the fort’s first well.

Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe has been busy mending ceramics this month, the majority of which are vessels bound for the oversize storage cabinet. Currently, Jo is focusing her efforts on a Bartmann jug, for which new pieces have been found. While the collections staff are always happy to find new mends for vessels already in the collection, it can mean a lot of work for the team if the new pieces belong to the interior of the vessel. In these cases existing mends will need to be taken apart before the new find can be placed where it belongs. This is the case with the Bartmann that Jo is working on. Several new sherds were found in the collection as part of a search for German stoneware, both for the reference collection, and for possible inclusion in the oversized storage cabinet. Luckily conservation staff typically use reversible adhesives when mending ceramics, and this one is no different. Jo uses gaseous acetone to weaken the adhesive and then gently pry apart the pieces to make room for the new sherds. She uses painter’s tape to give strength to newly mended sections and sets them in small plastic tubs full of sand so that they are aligned correctly as their adhesive dries.

Other artifacts Jo has been working on this month include part of a cast iron stove and an ivory finger ring. The partial cast iron stove was found in several pieces in front of the Archaearium last year and is totally enveloped in corrosion and soil. But an X-ray of the object revealed several words and numbers imprinted on the stove indicating manufacturer (A.J. Gallagher), city of manufacture (Philadelphia), and manufacture date (1858). The curatorial team did some research on the stove and found an advertisement in December 8, 1858’s edition of The Press, a Philadelphia newspaper, for the stoves. Jo is also doing a condition assessment on an ivory finger ring found in the L-shaped cellar discovered near the center of the fort. The ring is in two pieces and its size is approximately a 9.5.

Collections Assistant Lindsay Bliss will soon be floting soil samples on the Seawall again. Lindsay has been repairing and improving the float tank and after several testing cycles has it just where she wants it. She used tiny poppy seeds as “artifacts” and after her modifications, including switching from a 1mm screen to a 0.5 mm screen, she has recovered 95 of 100 poppy seeds that went through the flotation process. Having a high recovery rate for even the tiniest artifacts is important because many of the artifacts found by the team are of a similar size to the poppy seeds. Two prominent examples are tobacco seeds, a plant of primary importance to Jamestown and Virginia, and seed beads (named for their small size). Now that the flotation machine is in excellent working order, look for Lindsay on weekdays just east of the Dale House, weather permitting. She has her work cut out for her. Over 300 soil samples, collected from a wide variety of contexts during the last ten years of the project, and each containing 10 – 16 liters of soil are in the queue for processing.

Pigs have been on the mind of Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp lately. Jamestown is participating in an isotopic study of pig bones, providing 21 samples to a team of three researchers studying the origins of pigs that fed the colonists both at Jamestown and on its sister colony of Bermuda. Did the Jamestown pigs come from England? From Bermuda? Were they bred at Jamestown? Sixteenth-century Spanish explorers populated Bermuda with pigs, later generations of which fed their rival English colonists after their arrival in 1609, shipwrecked on their way to Virginia. The Bermuda National Trust is providing five samples of pig bones found in 17th and 18th-century archaeological contexts to the study led by Dr. John Krigbaum of the University of Florida, Dr. Michael Jarvis of Rochester University, and Dr. Charlotte Andrews of the Bermuda National Trust. The samples provided by Jamestown are mostly from pre-1611 contexts, with some from excavated from later fort-period features. The study will use isotopic tests of the bones in an attempt to determine where the pigs lived prior to their culinary demise. Stay tuned for more info as the research progresses.

Dr. Ashley McKeown, forensic anthropologist of Texas State University and long time collaborator with Jamestown Rediscovery, visited Jamestown this month to work with Associate Curator Emma Derry to continue their analysis of the four colonists excavated in October of last year. Ashley and Emma made significant progress on two of the individuals from the 1607 burial ground, containing individuals (all male) who died in the first few months of the colony’s existence. The first individual was the best preserved of the four. He was between 25 and 45 at the time of his death, likely 30 or older. His mouth was full of cavities and he also had a few missing teeth. There is evidence of arthritis in his neck and possible gout indicated by lesions in his hands and big toe. He was about 5’7″ and had moderately robust muscle attachment points indicating a life of moderate physical activity. The colonist’s pelvis was in unusually good shape compared to others previously studied at Jamestown, enabling Ashley and Emma to study the clues evident on its surface.

The second colonist, an individual of 15 or 16 years old, was aged largely by the state of his wisdom teeth. They were still unerupted, with half formed roots. Teeth are an oft-used tool for aging young people as their development follows a very rigid timeline. Once the wisdom teeth are fully erupted it becomes much more difficult to narrow down the age of young adults. Another clue that Ashley and Emma found was that the epiphyses (the round ends of long bones) of his femurs were unfused, another indicator of his young age.

Curatorial Intern Molly Morgan, a graduate of this year’s field school, is in the lab working with Senior Curator Leah Stricker and Assistant Curator Lauren Stephens to examine the temper, surface treatment, and vessel decorations of over 1500 sherds of Virginia Indian ceramics. “Temper” refers to the materials that Virginia Indian peoples added to clay as they made the ceramic vessels, often crushed oyster shell, pebbles, crushed quartz, sand, or a combination of those. The tempers were added to increase the porosity of the clay, helping to prevent or minimize shrinkage and cracking as the ceramic was fired by permitting moisture to escape as the heat is applied. “Surface treatment” describes markings or other actions that are displayed on the exterior body of a ceramic vessel, and can include simple-stamping (described below), impressions made by pressing the clay into fabric, baskets, or netting, cord-marking, or a plain/smoothed surface. Identifying tempers and surface treatments is the first step in understanding when and where a ceramic vessel was made. For example, the direction of the twist of a cord, Z-twist (clockwise) or S-twist (counterclockwise) can be identified when analyzing surface treatments. Archaeological studies have shown that there is a strong intra-communal tendency to use the same twist orientation, so researchers can use the presence of the other orientation to help trace interactions between different communities.

One of the most common Virginia Indian ware types found at Jamestown is tempered with crushed shell, and the surface of the vessels were imprinted with a series of parallel and sometimes crossing lines, created by beating the ceramics with a small wooden paddle wrapped in leather cord. Referred to as simple-stamping, the paddling of the ceramics was not purely decorative; it was a step in the shaping and compressing of the clay prior to its firing. The type is called Roanoke Simple-Stamped, and its manufacture and use has been found in association with sites dating to the late Woodland period, which includes the early 17th century. This ceramic type would have been common in the local Virginia Indian communities when the English arrived at Jamestown.

As Molly identifies tempers, surface treatments, and vessel decorations, Leah is entering the data into the database. This work is part of the ongoing development of the Reference Collection for Native Ceramics, so when sherds with unique characteristics are identified, they are maintained in the vault for future assessment. Molly has also collaborated with Jamestown’s conservation staff to photograph many of the sherds, and her work has helped to identify and mend together sherds of at least three unique vessels, which will be maintained in the reference collection. One of the newly mended vessels is an unusually small Roanoke Simple-Stamped pot, recovered from the East Bulwark Trench nearly thirty years ago. It bears ample evidence of being used, fire having blackened every sherd.

Molly’s work will be ongoing throughout the fall semester.

related images

- 2025 Kids Camp first session attendees with archaeological staff.

- 2025 Kids Camp second session attendees with archaeological staff.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid, manager of the Kids Camp, gives the kids an overview of the excavations at the cellar site.

- A tray of earth that will soon be screened for artifacts

- Troweling in the plowzone at the cellar site

- Emptying excavated soil into a screen prior to looking for artifacts

- A camper holds lead sprue he found while screening. This sprue is the waste portion of shot produced via a gang mold.

- Archaeological Intern Dominic Angioletti gives an assist to a camper as he empties screened soil into a pile. The soil will later be used to fill sandbags or backfill excavations.

- A camper holds the Standing Liberty quarter she found while screening.

- A camper examines the trash of one of the archaeologists on staff, pondering what he can learn about its owner.

- A camper holds a sherd of ceramic she found while screening.

- Campers and Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch trowel away at the cellar site.

- Screening soil at the cellar site

- Two campers hold mending ceramic sherds they found while screening at the cellar excavations.

- A camper holds a nail she found while screening through soil from the cellar excavations.

- An overview of the cellar site during Kids Camp.

- Kids Camp is serious business.

- A row of kids trowel at the cellar site.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid gives the campers a lay of the land at the cellar site on the first day of camp.

- A camper examines a dog skull in the Jamestown collection.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp shows campers how to identify common bones in the Jamestown collection.

- A camper shares his illustrations of artifact types found while sorting.

- Campers learn the fundamentals of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) from Director of Archaeology Sean Romo.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo instructs campers in use of one of the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) machines. The kids are surveying inside the 1680s Church Tower where the remains of the 1617 church’s west foundations lie under a glass floor.

- A camper in the Ed Shed searches for artifacts in objects excavated from the fort’s first well.

- Director of the Archaearium Museum and archaeologist Jamie May gives a tour of the museum to Kids Camp attendees.

- Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb instructs the campers on archaeological illustration.

- A camper holds an iron spike he found at the cellar excavations.

- A kids camp attendee holds a piece of a glass vessel he found while screening.

- Screening for artifacts at the cellar excavations

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and campers share some of their finds with visitors.