Amanda Nedell, 2024 Curatorial Intern and Lauren Stephens, Collections Assistant

Amanda Nedell recently completed an 8-week long internship with Jamestown’s Curatorial staff, focusing on a ceramic ware type called Spanish Coarseware. Most of the Spanish Coarseware vessels in the Jamestown collection are olive jars. Amanda recently graduated with her Bachelor’s degree in Anthropology/Archaeology from Mercyhurst University where she worked in the archaeology lab. To find out more about her project with us, continue reading.

Of the Spanish Coarseware ceramics excavated at Jamestown, most of the assemblage has been identified as olive jar fragments. These vessels are largely unglazed and have coarse fabric with a high rate of absorption. Despite their name, olive jars were known to be used to transport far more than just olives in brine. Water, wine, olive oil, vinegar, honey, chickpeas, various nuts, beans, pitch, gunpowder, and bullets are all known to have been stored in these large vessels (Goggin 1960:6; Avery 1997:190-195). The absorbent nature of the ceramic acted as a form of preservation; evaporation from the exterior of the vessel allowed the contents to remain cool (Deagan 2002:32). The primary use for olive jars was in commercial transportation, and this is likely how they came to be in the archaeological record at Jamestown. While no evidence of this exists at our site, olive jar fragments on other sites were used as architectural fill when constructing buildings and buried beneath dirt floors because the fragments acted as a natural dehumidifier (Avery 1997:103).

Olive jars were wheel-thrown in a few different shapes and sizes. At Jamestown, only two vessel shapes are found, globular (more round) and ‘carrot-shaped’, and both date to the late 16th to early 17th century. While most of the vessels found at Jamestown are incomplete as partially mended vessels or remain fragmentary as unmended sherds, at least 13 to 15 olive jar vessels are represented by over 1,000 individual sherds recovered to date.

Before we began this process, only 3 mended vessels and a few mended sections of vessels existed in the Jamestown collection, and most of the ceramic sherds were in long term storage in Jamestown’s lab facility. All of those fragments were pulled, assessed, and labeled before the mending could begin. The process of mending ceramics includes the use of both acetone and of 15-20% acryloid B-72 (w/v in acetone), an adhesive solution that also allows for disintegration and reversal if necessary. Prior to working on new mends, Associate Curator Emma Derry, Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens and I disassembled old mends to ensure the stability of the mended ceramic vessel. This was done by soaking acid-free cotton in pure acetone and wrapping it around the mended areas, allowing for the material used for the mend to dissolve.

The cross mending process is similar to putting a puzzle together, except we often don’t know exactly what the final result will look like. As we crossmend fragments, we group them together, creating a vessel or a “complete” puzzle. With olive jar fragments our research helped us to understand the possible shapes and sizes, but the color and coarseness of the fabric is quite similar which means that close analysis of the sherds is needed to mend them or put them with other fragments that closely resemble each other. We hoped that the crossmending process would help us to better understand how many vessels were present in the collection, and their shapes and sizes. This information then allows us to theorize on what they may have contained when they were shipped to Jamestown.

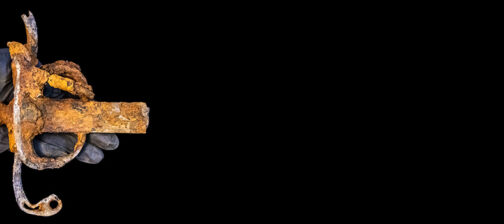

Different pieces are found all over the site and putting them together, even if the vessels aren’t complete, allows us to better understand different areas of the site and how the vessels were used. Two of the most complete vessels in the collection were both found in the Factory feature just outside the fort, a structure in use during the early fort period. The colonists were using fire for distilling and metallurgical purposes in this area, so they may have repurposed these olive jars to hold water for drinking, or to act as a 17th century fire extinguisher.

One of the vessels found in the Factory feature has been on display in the Archaearium museum since the museum’s opening in 2007. We temporarily removed the vessel from display for reassessment and cleaning. I was able to find one additional mend to this vessel, and began the process of disassembling and cleaning it.

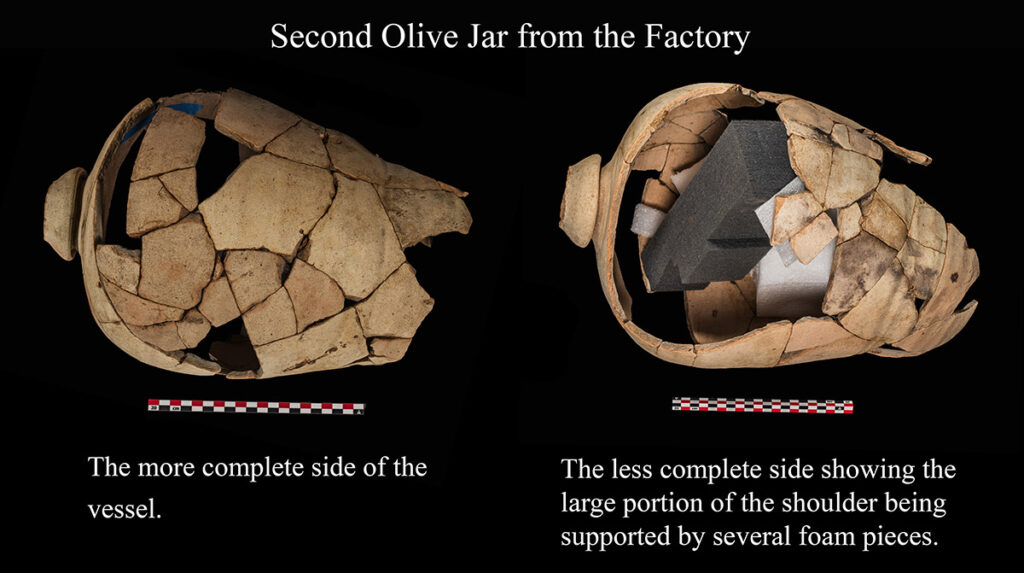

I spent a large part of my internship reassembling and mending another of these two vessels. This olive jar is approximately 40 centimeters in length and, by my estimate, 60-70% complete. The vessel includes 60 sherds mended together, ranging in size from almost the entire top part of the vessel with the rim and shoulder, to sherds that are about the size of a thumbnail. It took around 5 weeks to completely find and mend this vessel. Following the mending process, I joined Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens in the photography process of the vessel with Senior Staff Archaeologist and Staff Photographer, Chuck Durfor.

Following the completion of the mending portion of the project, I had the privilege to use Jamestown’s Portable X-Ray Fluorescence, or pXRF, machine to analyze the chemical and elemental makeup of the glaze and fabric on various Spanish Coarseware vessels. We also compared several forms of unknown ceramic fragments to a known fragment of Spanish Coarseware to identify if the unknown sherds were, in fact that ware type. Based on its shape, one of the fragments that was previously classified as olive jar is now thought to be an orza, a Spanish Coarseware storage jar with a flat bottom. Our pXRF analysis of the orza fragments has confirmed that based on the composition of the clay, they are Spanish Coarseware!

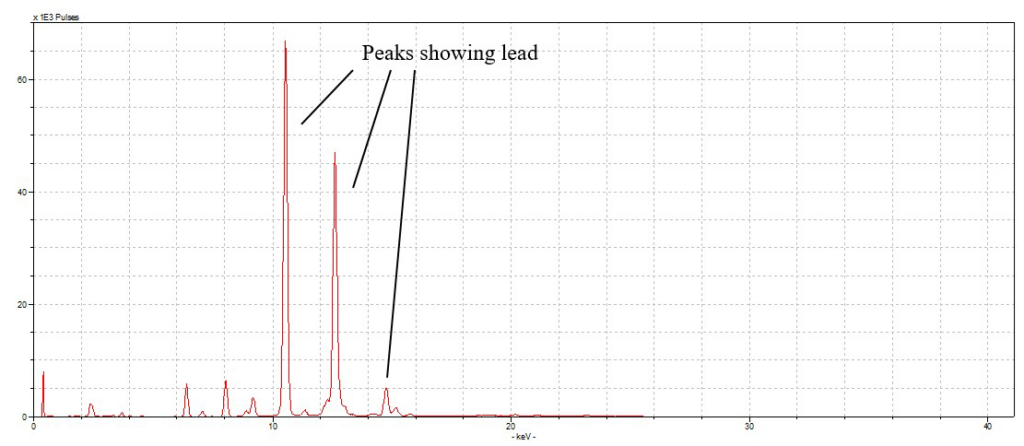

After using pXRF on the various vessels, including the orza, olive jar fragments, and mercury jar fragments, the results were uploaded onto special software, called Artax, allowing me to read the wavelengths and identify which elements can be seen within the sherd. In addition to confirming that the orza was Spanish Coarseware, we were also able to test the glaze on different sherds. One small olive jar, previously thought to be covered on the interior surface with black pitch, was tested and inspected more closely and was found to actually have a dark green lead glazing (shown below). I completed this part of the project with the assistance of Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens and Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins.

This entire process has been incredibly rewarding, even though it was an extremely slow and tedious process, I was able to mend the majority of a vessel. I was also able to learn scientific analysis techniques on a sophisticated piece of machinery, an experience that would be hard to replicate elsewhere. It is my hope that the vessels I analyzed and mended will be used to educate the public and assist in the understanding and study of the Jamestown site overall for years to come.

references

Avery, George E. 1997. Pots as Packaging: the Spanish Olive Jar and Andalusian Transatlantic Commercial Activity, 16th-18th Centuries. Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI.

Deagan, Kathleen 2002. Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies of Florida and the Caribbean Vol. 1: Ceramics, Glassware, and Bead, expanded and revised from 1987 edition. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Goggin, John M. 1960. The Spanish Olive Jar: An Introductory Study. In Papers in Carribbean Anthropology, Vol. 62, Irving Rouse, editor, pp. 3-48. Yale University Publications in Anthropology, New Haven, CT.

Peacock, Caroline 2023. From Olive This: A Characterization of the Spanish Olive Jar in mid-16th Century New Spain. Master’s Thesis, University of West Florida