Shoes are among the most personal artifacts in Rediscovery’s archaeological collection. Unlike so many things from the 17th century that are no longer used today, we still wear shoes! We have all probably experienced the discomfort of poorly fitting shoes, a limp that comes with a pebble stuck inside a shoe, or received a tiny pair of shoes for children’s feet that are either too large or too small. The colonists at James Fort undoubtedly encountered the same sorts of problems in the early 1600s. Therefore, almost more than any other artifact, they offer us a tangible link to the early colonists, and remind us that despite the passage of 400 years, many aspects of human life remain unchanged.

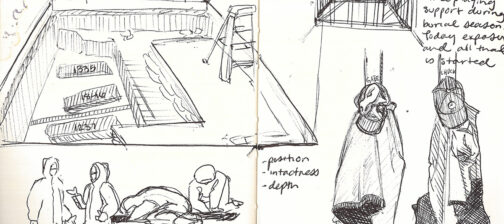

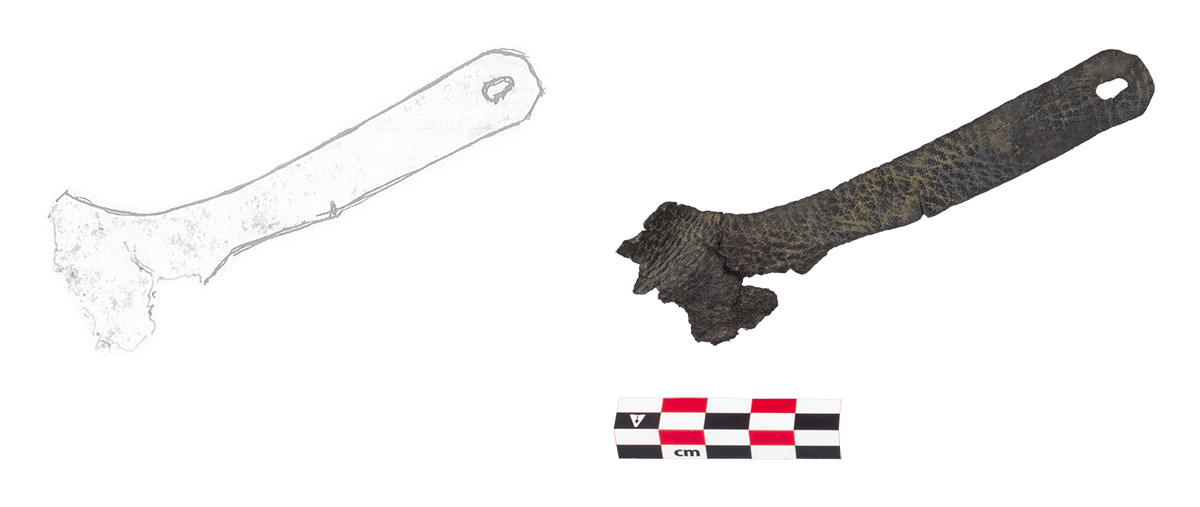

Leather shoes are a type of artifact that is almost solely (a little pun there for you) recovered from waterlogged features like wells. The waterlogged, anaerobic environment of the lower layers of a well significantly slows bacterial degradation of leather. A total of 16 database records were made to capture fragmentary leather shoe elements excavated from the Governor’s Well feature. At least two, maybe three, leather shoes are represented by the fragments, including parts of shoe soles as well as upper elements of shoes. Also included is one latchet, or the leather strap that would have helped to hold a shoe onto a 17th-century foot!

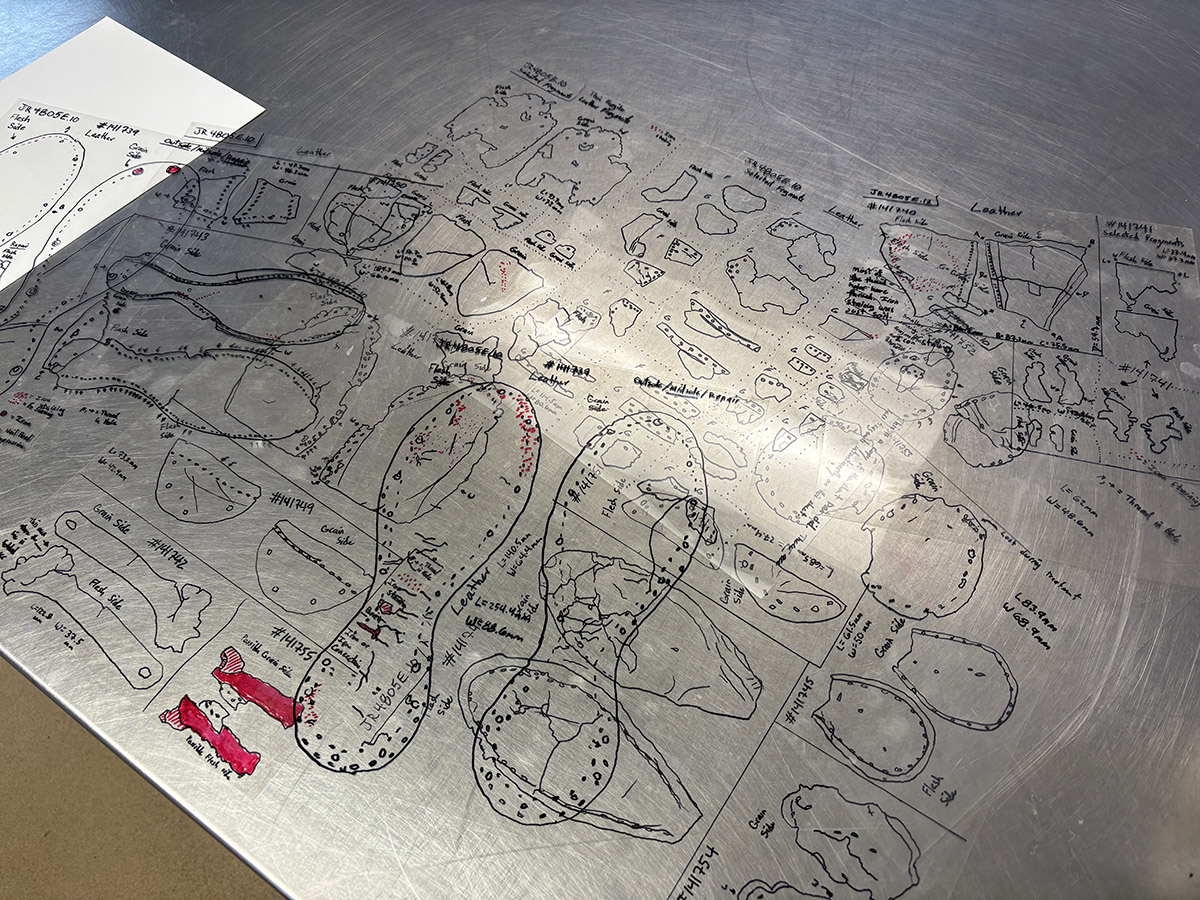

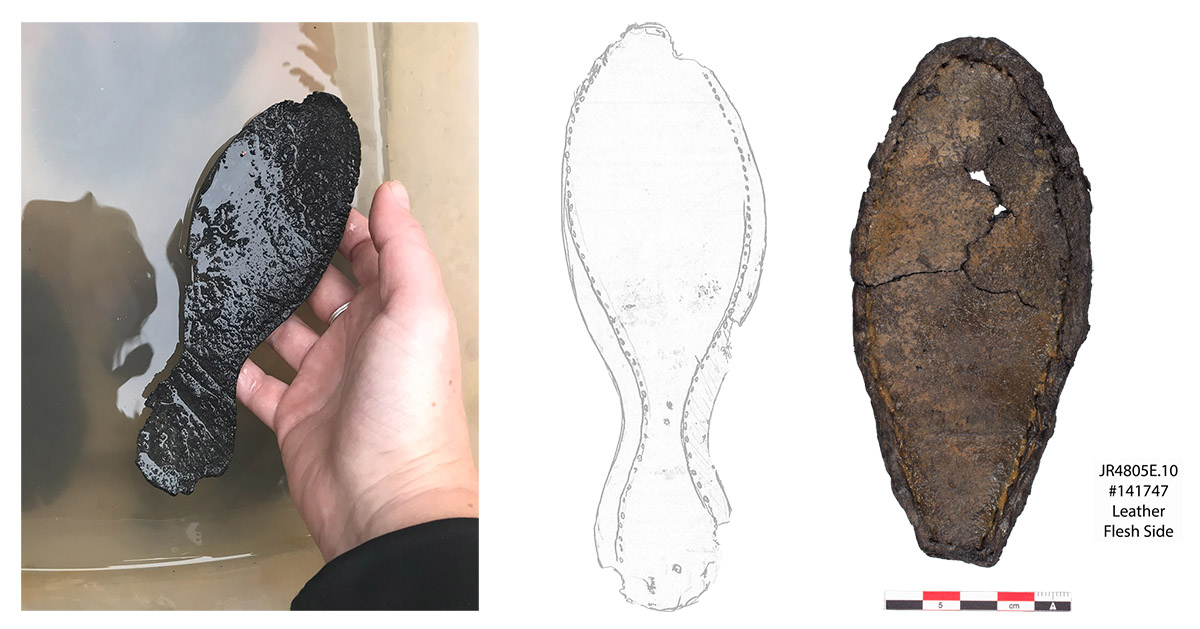

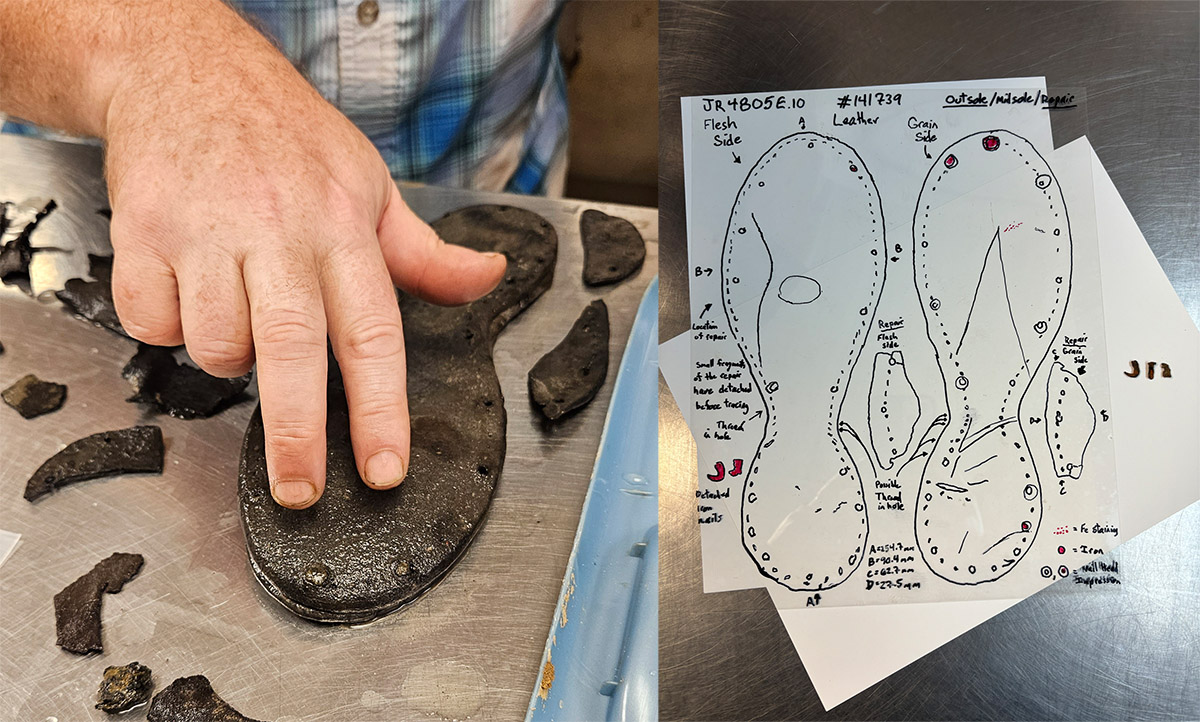

Because the leather was wet when excavated, the fragments were kept wet as they came into to the Rediscovery’s lab. The first conservation task was to make a detailed record of each piece, what it looked like, its size, and any notable characteristics. The fragments were drawn and traced onto Mylar (thin transparent film) to record elements on the grain (skin exterior) and flesh (skin interior) sides including lace holes, thread holes, shoe nail holes, wear patterns, iron staining, large and small cracks, etc.

The first shoe is a matching insole (#141747) and outsole (#141743). The outsole is the part that faces the ground, and the insole is the part of the shoe that faces up towards the foot. Usually the two are separated by a midsole, but we haven’t identified one belonging to this specific shoe. The outsole and insole were excavated separately, but when laid on top of each other, the thread holes that stitched the two elements together align. The outsole, pictured below, even still had some of those threads in the holes!

Measurements of shoe leather are made in specific ways. Leather thickness is often given in ounces for shoe uppers, and irons for shoe soles. One ounce = 1/64″ and one iron = 1/48″. The term iron originates from the plates of iron that were used by European shoe-makers to measure the thickness of leather used for various parts of the shoe. The outsole of the first shoe is a 6-iron, meaning that the leather is 0.125″ thick. The insole is 8oz, also 0.125″ thick, same as the outsole. In total, it measures 18.93cm in length and 6.66cm in width at the ball of the foot. These measurements indicate the shoe fit a modern US child’s size 11-12. Whether it worn by a child or a petite woman, we may never know, but it shows shows the presence of women and children at the Fort around the time the well was filled with trash.

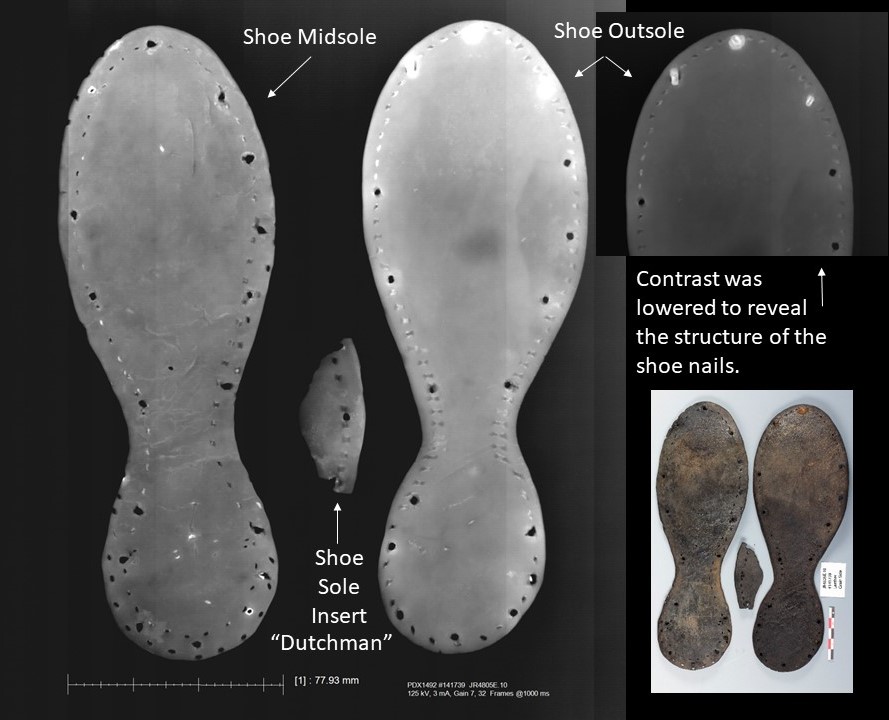

The second shoe is represented by an outsole, a midsole, and an extra heel fragment. When excavated, the outsole and midsole were held together by two visible iron nails near the toe. The heel fragment was found separately and matched the shoe because the thread and nail holes and heel curvature coordinated. A diagonal slice was made down the middle of heel fragment to extend and fit a added scrap of leather so that it fit the heel curvature and the rest of the shoe.

Larger than the first shoe, this outsole is 8-9 iron (0.167″ – 0.188″ thick), the midsole is 5 iron (0.104″) thick, and the additional heel lift is 8oz thick (0.125″). In total, the outsole measures 25.44cm in length and 8.86cm at the widest point, making it about a modern US men’s size 6-7.

Two iron shoe nails (or hobnails) holding the midsole and the outsole together are visible near the toe end of the outsole. This shoe was X-rayed by conservators to determine the number and location of shoe nails, and how they may be problematic in conserving and stabilizing the leather. The X-ray (below) showed more nails and nail elements are in the leather than visual inspection revealed! One nail has a clinched point, that is, it was bent over to ensure the shoe was securely attached. In addition, documentation revealed other interesting information about this shoe’s wearer. Near the ball of the foot is a “Dutchman,” a small leather fragment that was inserted in between the outsole and midsole when the shoe was made (see drawing above). This fragment indicates the shoe was made-to-order, and the additional 8-9 iron piece was likely placed to help correct a supination or overpronation of the wearer.

After recording and x-rays were complete, conservators cleaned the leather fragments with soft brushes and probes under water or with gently flowing water. As additional observations were made during the cleaning process, new aspects of the shoes (e.g. additional thread holes, wear patterns) were recorded on the Mylar tracings.

Next, the leather was immersed into sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to remove iron salts. Leather will shrink during the drying process, even if the shrinkage is undetectable. Iron salts, however, do not shrink. If they are present as the leather dries, the iron salts will cause the leather to tear. Iron salts left on the leather long-term could also cause chemical degradation to the leather over time.

Drying is the last major conservation step, conducted with either a freeze-dryer or through a slow-drying process. In the case of the shoe leather from the Governor’s Well, our conservation team decided to do a slow-drying process. To reduce shrinkage and distortion while drying, the leather was immersed in glycerol for several days, and then removed from immersion to slowly dry. The slow-drying process is ongoing.

Ideally, after conservation is complete, the leather shoes and other leather fragments will be dry and supple with little to no shrinkage, thereby allowing these precious objects to be handled and studied by researchers.

Just as they do today, shoes in the 17th century experienced a lot of wear and tear. They wore out or were outgrown, as evidenced by shoes recovered from Jamestown’s wells. By reflecting on artifacts as seemingly mundane as shoes, we can gain a deeper appreciation for daily life in early colonial America., and foster our connection to those who came before us.