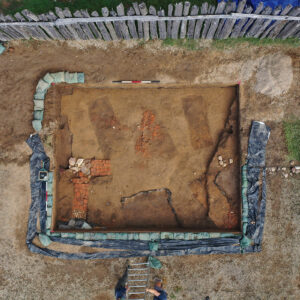

The Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists are busily preparing for excavations of burials at both the 1607 burial ground and at Smithfield just south of the Archaearium. The team is raising the burial structure at the 1607 burial ground, designed to protect the human remains from the elements and prevent contamination of the ancient DNA by modern DNA. Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown designed the structure here and the one that will protect the burial at Smithfield, soon to be erected as well. The team is on a tight schedule, coordinating their efforts with the arrivals of outside colleagues in the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and biological anthropology fields. Peter Leach, a longtime collaborator from GSSI, will be traveling to Jamestown to assist the team with their imaging of the remains prior to excavations. Before Peter arrives, the archaeologists need to remove all the backfill from the 2000s excavations and excavate any features obstructing GPR and further excavations into the grave shafts. At the 1607 burial ground, two out of the three burials slated for excavation this fall have brick rubble strewn across the surface of the grave shafts. This brick rubble may be the remains of a later brick hearth. The lack of intact bricks likely indicate that the colonists robbed of much of it for use elsewhere. Like other archaeological features at Jamestown, the brick rubble will be recorded via photography (both traditional and drone), photogrammetry, and surveying so that we can have as complete a picture as possible prior to its removal and processing by the curatorial team. The archaeologists are going to look at records of past excavations to see if there may be more evidence of a later building that this possible hearth might belong to.

The planned GPR surveys will guide the team when excavation begins. Not only will the GPR allow the archaeologists to see the layout of the human remains in the grave shaft, it will also tell them how deep the remains are in the ground. This information is crucial for the team to carefully expose the remains. All of this work needs to be done before the arrival of Dr. Ashley McKeown, Biological Anthropologist at Texas State University. Dr. McKeown will work with Emma Derry, Jamestown Rediscovery Associate Curator, to analyze the remains both in situ and in the lab.

The archaeologists at Jamestown wear many hats and they have donned their construction helmets at the 1607 burial ground while building the burial structure. Protecting the human remains from the elements and contamination has proven to be a winning strategy for successful DNA recovery. One of the primary ways they do that is with the construction of a burial structure. A wood-framed building with plastic for walls and a roof, the structure is essentially a greenhouse, keeping the interior several degrees warmer than the outside. But its purpose is to shield the burials from the weather, people, and the animals that call Jamestown home. In addition to the damage that these elements can cause to the remains, people and animals could also potentially “muddy the waters” of the ancient DNA with their own. To further minimize the chance of this happening, the team wears full Tyvek suits, masks, and even booties over their shoes as they get close to exposing the remains. This level of caution has proven effective in producing viable DNA in the past, and so the team is sticking with what works.

Once the burial structure at the 1607 burial ground is complete, the archaeologists will build a second one to protect the single grave that will be excavated in Smithfield, just south of the Archaearium. The team is approaching the excavations here with trepidation…they’re not quite sure what condition the remains will be in. Smithfield floods with regularity now, something it didn’t do when the Jamestown Rediscovery project began 30 years ago. Smithfield is lower than the surrounding area, and archaeological evidence suggests that 1 or 2 feet of soil was removed from this space historically. This is evident just by looking at the landscape, as Smithfield has a shallow bowl shape, its edges visibly higher than its interior. The plowzone, the layer scarred by centuries of farming, is only a couple of inches thick here, when it averages about a foot thick on most of the island. The soil here may have been taken for landscaping fill on other parts of the island around the turn of the 20th century. As a result of this shallower surface, the burials here are that much closer to the flooding, some of which trickles down to where the remains are. Additionally, GPR shows that the groundwater here is close to the surface and may also be adversely affecting the remains. Burials subjected to wet/dry cycles at Jamestown have manifested deteriorated bones, sometimes to the point of being soft to the touch. The condition of the bones found inside will be instructive as to whether it’s worthwhile excavating any other burials found at Smithfield. They keep turning up . . . there are two others in the square containing the one that will be excavated, but they are far enough away not to interfere with the excavations.

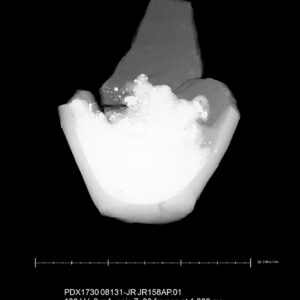

Whereas last month Delft tiles covered the big table in the Vault, this month it’s crucibles. There are at least fifty crucibles in the Jamestown collection. These ceramic vessels were used to hold various substances before heating them to extremely high temperatures. The colonists may have been using crucibles for metallurgy and glass making in their attempts to produce a profitable export for the Virginia Company of London investors in England. Dozens of crucible fragments were found in the fort’s first well and in the Factory but interestingly very few were found in the second well. Many of these crucibles were made in Großalmerode, Hesse, in present-day Germany. The crucibles made there were known for their high quality, able to withstand the extremely high temperatures necessary for the melting of materials that they contained. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of these crucibles is that the majority of them contain residues from the processes they were used for. Umberto Veronesi, PhD, Research Fellow at VICARTE in Lisbon, Portugal, visited Jamestown this month to continue his research on the residues found inside the crucibles. He took 40 additional samples of the residues from crucibles, a melting pot, and also from finished glass samples for analysis by scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectrometry. Through these processes, Dr. Veronesi is able to determine the relative prevalence of elements in them. By also taking samples from the finished products he may be able to determine if any of the glass was produced locally.

The results of Dr. Veronesi’s past research indicates that the colonists were experimenting with extracting silver and copper from local rocks. They were also attempting to produce copper alloys, with the presence of zinc and tin suggesting brass and bronze alloying respectively. Dr. Veronesi also discovered glass encrusted on the side of many of the crucibles, evidence that jibes with the historical record indicating the colonists conducted a “tryall of Glasse” to determine if glassmaking could be a profitable enterprise in Virginia. Interestingly some of the crucible sherds have residues on the edges that mend with other sherds. This is evidence of crucibles breaking during the heating process.

The presence of hundreds of pieces of glass cullet in early fort period contexts (notably the First Well and the Factory) at a time when the fort’s buildings didn’t have glass windows indicates that it was purposely sent to Virginia with some of the earliest colonists. Cullet is waste, in this case, the edges and center pieces of crown glass, their shape disqualifying their use in windows. When put in a fire with the raw materials necessary for glassmaking, the necessary temperature for creating new glass is lowered, lessening the amount of wood and effort necessary for the process.

There are two main shapes of the crucibles in the Jamestown collection, triangular and conical. The triangular examples were meant to be stacked during storage and transport, with smaller ones inside the larger ones similar to Russian nesting dolls. The triangular examples were manufactured in Hesse, their corners allowing for a fine stream of liquid while pouring. The conical ones are of unknown origin, but similar examples have been found in archaeological sites in Quebec. Four of the crucibles in the collection bear a maker’s mark, with one imprinted with “PTV GER”, believed to represent Peter Topfer, Großalmerode. Topfer was a crucible producer in that part of Hesse in the early 17th century.

Other ceramics in the collection related to metallurgy and glass making include a large melting pot and several cupels. The melting pot is also ceramic and is used to melt materials but is much larger than the crucibles. A sample of the residue on the melting pot was among those taken by Dr. Veronesi during his latest visit. Cupels are shallow vessels typically made of pressed bone ash. When trying to separate gold or silver from impurities, pouring molten gold or silver into a cupel will result in the precious metals pooling on the cupel’s surface while impurities sink into its pores.

In addition to supporting Umberto’s research, lots of crucibles and crucible fragments have been pulled from long term storage in order to embark on a crossmending project. We hope to reconstruct the vessels to better understand how many crucibles in total were present at the site, the distribution of crucible sizes and shapes, and to better understand the contexts from which the fragments came. Crossmending ceramics makes the objects more complete, and therefore excellent resources for display or photography, but archaeologists also crossmend in order to investigate research questions that the material culture of Jamestown can help to illuminate!

Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp continues her work on layer “N” of James Fort’s first well. The layer is chock full of fish bones and she’s come across examples of shark, sucker fish, drum fish, and sheepshead to name a few. These bones and the hundreds of thousands of others found in the first well — called “John Smith’s Well” because he mentions its construction in late 1608/early 1609 during his tenure as the colony’s president — speak to the diet of the colonists during the Starving Time winter of 1609/1610 as the now-fouled well was used as a trash pit during the town cleansing ordered by Lord De La Warr in June 1610.

Associate Curator Janene Johnston presented a paper that she co-authored with Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin and Director of Living History & Historic Trades Willie Balderson at the biannual Fields of Conflict Conference in Savannah, Georgia. The presentation combined evidence from historic documents and archaeological finds to show how the English adapted to the more immediate threat of the Virginia Indians and the ever changing relationship between the groups.

Conservators Dr. Chris Wilkins and Jo Hoppe are carefully conserving four bottles from Mount Vernon. The bottles, found in storage pits in the cellar of the Mansion, are among 35 discovered there, 29 of which still contained fruit stored inside in the 18th century. Chris and Jo stress that their task is to preserve as much of the original glass as is possible, not to make the bottles more aesthetically pleasing. Because they’ve been subjected to wet conditions in the cellar, the bottles have suffered from “glass disease” where sodium and silica leave the glass, causing its layers to flake off. The conservators are first consolidating the entire bottle to prevent any further deterioration. To do this, they are applying a Paraloid B-72 solution. They then treat each area of the bottles individually, using acetone to remove the B-72, and acetone dipped cotton swabs and scalpels to remove dirt. Once the area is clean, two different strength B-72 solutions are used to protect the glass, a 5% B-72 solution to get into all the nooks and crannies and protect those surfaces, and an 8% B-72 solution to protect the area as a whole.

related images

- The Jamestown Rediscovery team prepares the area of the 1607 burial ground where this year’s burial excavations will take place. The three dark rectangles are the top of the grave shafts. The brick scatter at center may be a robbed hearth from a later building. The brick and cobblestone feature at left is a chimney base for a fort-period building that paralleled the west palisade wall and was approximately 92 feet long.

- The archaeological team conducting excavations at the 1607 burial ground

- A drone photo of the area of the 1607 burial ground containing the three graves to be excavated this fall (the three roughly parallel dark rectangles).

- The brick and cobblestone chimney base for a large fort-period building built inside and running parallel to James Fort’s western palisade wall. The structure was built on top of the 1607 burial ground.

- The archaeological team forms a bucket brigade to remove water from the 1607 burial ground following a rainstorm.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo and Archaeological Field Technicians Ren Willis and Hannah Barch score features in a square south of the Archaearium. This square contains the burial that will be excavated in the next few weeks. Two other burials are also in this square.

- A drone panorama of the excavations south of the Archaearium. The square at the right of the photo contains the burial that will be excavated here in the coming weeks.

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis points to the burial that will be excavated south of the Archaearium.

- Archaeological Field Technicians Ren Willis, Hannah Barch, and Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford score the features in the burial area south of the Archaearium. They’re preparing the area for record photography.

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis trowels away at the area around the burial south of the Archaearium.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas explains the upcoming burial excavation south of the Archaearium. The scored burial can be seen at the bottom of the photo.

- Buildings and Grounds Manager Shane Shortt instructs the archaeological crew on safe operation of power tools prior to their building of the burial structures. Shane recently received his OSHA 30 certification.

- Archaeological Field Technicians Eleanor Robb, Josh Barber, and Hannah Barch score and take measurements of the three burials found inside a square just south of the Archaearium. The center one is scheduled for excavation in the coming weeks.

- Dr. Umberto Veronesi explains his research and his findings so far to the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeological team.

- A small triangular unused crucible in the Jamestown collection

- A crucible fragment found in the fort’s first well. Melted glass adheres to the vessel.

- A conical crucible in the Jamestown collection

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker holds two crucibles containing lead residue.

- The base of a crucible bearing the maker’s mark “PTV GER” believed to represent Peter Topfer Großalmerode

- A tiny unused triangular crucible in the Jamestown collection

- Two partial crucibles. Note the black residue on the right fragment.

- An x-ray of a partial crucible. Lead residue shows up as bright white as the x-rays cannot penetrate it.

- Cupels in the Jamestown collection

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker holds a fragment of a melting pot in the Jamestown collection.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp holds sucker fish bones she found while sorting through faunal remains from James Fort’s first well.

- Shark vertebrae found in James Fort’s first well

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp holds bones belonging to a red or black drum fish. These were found in James Fort’s first well.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp sorts through the thousands of fish bones found in James Fort’s first well.

- Associate Curator Janene Johnston presents at the Fields of Conflict Conference in Savannah, Georgia.

- Flooding at Jamestown September 24, 2024

- Flooding of Smithfield, September 23, 2024. The burial excavation south of the Archaearium is the sandbag lined square at right closest to the center of the photo.

- Looking east from inside James Fort. The colony’s partially reconstructed first church is at left and the barracks are in the distance.