Two conspicuous white, wood-framed, plastic-covered buildings sprung up at Jamestown this month, the semi-transparent plastic hiding the flurry of activity inside. The two buildings, one near the southwest corner of James Fort and another in Smithfield just south of the Archaearium museum, are the locations of this year’s burial excavations. At the James Fort location, in an area close to the Seawall called the 1607 Burial Ground by the Jamestown archaeologists, three people were excavated this month. These people died in the very first months of the settlement and were buried inside the fort so as to hide the colony’s dwindling numbers from the Virginia Indians (following instructions from the Virginia Company of London). About five hundred feet to the northwest, the second burial excavation location is part of a huge graveyard centered on Statehouse Ridge, the final resting place of over 100 colonists.

In regards to the conditions of the remains, the pattern from prior years’ excavations held true again. The three people excavated in the 1607 Burial Ground were in better condition than that of the colonist in Smithfield. This is likely due to the difference in elevation between the two graveyards. The 1607 Burial Ground is on high ground because the fort was purposely built there to make it more defensible. This means the colonists’ remains are high above the water table beneath them. Because building on the high ground was still sound military engineering 254 years later, the Confederates and their enslaved workers built Fort Pocahontas unknowingly overtop the footprint of James Fort in 1861. This resulted in the colonists’ graves being covered in several feet of Confederate earthworks, protecting human remains from rainwater as well.

In Smithfield the situation is quite the opposite. The field is low lying and is increasingly flood prone, meaning the human remains there are exposed to wet/dry cycles that cause decay. In Smithfield and elsewhere at Jamestown archaeologists have found that human remains that are exposed to wet/dry cycles are softened and eventually dissolve, ultimately becoming no more than stains in the ground. This is the case with this burial as well. Sean Romo, Director of Archaeology, likened the condition of this colonist’s skull to wet cardboard. But much of the colonist’s remains here are worse than that, being soil stains only. The skull is the only portion of the remains that partially survives.

In a case of bad timing, Hurricane Melissa was in the Atlantic during the excavations and though the eye was just west of Bermuda, approximately 600 miles away from Jamestown, it caused a tidal swell that inundated Smithfield via the Pitch and Tar Swamp. The excavation site was well protected with layers of sandbags and an earthen berm built by Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford using a backhoe. However the site was flooded not from the surface, but by water percolating sideways out of the earthen walls defining the excavation area. Luckily the archaeologists were able to get much of the data they needed prior to the flooding, but the remains are still underwater. Once the site dries out the archaeologists will investigate the feasibility of extracting some or all of the remains for further analysis.

At the 1607 Burial Ground the remains are in better shape, though one out of the three, who happens to be a bit higher up than the other two, is in the best shape. This burial, designated JR1850, is the northmost of the three and was excavated by Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley, Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas, and Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch. It’s probable that this individual was not shrouded or was only loosely shrouded as no pins or aglets were found and the positions of the shoulders, knees, and ankles don’t suggest the body was tightly wrapped. Initial observations by Texas State University’s Forensic Anthropologist Dr. Ashley McKeown and Associate Curator Emma Derry include the presence of erupted third molars (wisdom teeth), which indicate that this person was an adult. Further examination in the lab may give further clues to a more specific age range. The shape of the skull and jaw and the robusticity of the limb bones indicate that he was male.

The other two burials may be related temporally, probably being dug close to the same time as they are next to each other and oriented very close to true east/west (towards Jerusalem as well as paralleling the southern palisade wall and James River) as opposed to the majority of burials here that are perpendicular to the western palisade wall. This could even indicate that they were buried prior to the construction of the fort’s western wall. The western ends of the burials begin at the same easting, suggesting that these individuals were interred in a row around the same time. Each burial had a nail found at the colonist’s elbow, the southmost burial (JR1486) at the right elbow, the one just to the north (JR1454) at the left elbow. These individuals were not buried in wooden coffins, making the discovery of the nails notable. Whether the nail placement is intentional or accidental is unknown. Aglets were found in both of these burials. Aglets were thin metal objects, attached to the ends of laces to prevent fraying and ease the threading process. A modern equivalent is the hard plastic wrap at the ends of shoe laces. Their importance is evident to anyone who’s tried tying their shoelaces after the hard plastic has worn off. Aglets in burial contexts typically indicate that the deceased was buried with a shroud, the aglets used with thread to secure the shroud around the body. As the shroud and thread used to secure them typically don’t survive 400+ years underground, aglets are often the only artifact at Jamestown that suggests a shrouded burial.

These two burials are in substantially worse shape than the northmost, with large sections of the skeleton missing. JR1486, excavated by Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford and Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber, was cut by a posthole and part of a palisade wall (a different one than one of the fort’s original walls). In archaeology, a feature that cuts another is newer than the one being cut. A common example of this at Jamestown is the presence of farming plowscars running through historic features. Because the scars cut through the historic features we know they are newer than the features they cut.

The best preserved portions of the remains in JR1486 were those that were elevated in the burial shaft, including the cranium and lower legs. The grave shaft is too short . . . the individual’s cranium is pressed against the northwest corner of the shaft, with their chin touching their chest. Also, the left leg is twisted below the right. One theory explaining this is that the individual was shrouded and interred upside down accidentally. The colonists burying the deceased discovered their mistake and then flipped him over, causing the leg configuration. Preliminary field observations by Dr. McKeown and Emma suggest JR1486 is young, probably a teenager, and was less than five feet in height.

A nail was found by the right elbow and three aglets atop the abdomen, out of a total of four aglets discovered in this burial. Notably these aglets were found near the middle of the body which is unusual if they were related to a burial shroud. In other previously excavated colonists aglets associated with burial shrouds are found near the head and feet. These aglets instead may have been part of his clothing.

A foot to the northeast, JR1454 was excavated by Staff Archaeologists Natalie Reid and Ren Willis. This is the second of the two similar burials (JR1486 being the first). Like JR1486, the grave shaft was too small for its occupant. As a result, the individual’s head and feet were propped up against the edges of the grave shaft, and like the person in JR1486, their chin rested against their chest as a result. Also like JR1486, the legs and feet were in better condition than most of the remains, likely due to their elevated position. Preliminary analysis of the bones and teeth indicate this colonist was likely male and was an adult.

The reason for the burial excavations is to learn as much as we can about these people who rest in unmarked graves, using science to piece together parts of their identity whenever possible. Each year our collections and conservation teams take samples from the petrous portion of the skull, a dense area surrounding the inner ear that preserves DNA exceptionally well. And though DNA gets most of the attention, there are several other tests that outside consultants perform using samples gathered in situ and in the lab. Soil samples are taken at various key locations in the burial, including where the lungs, stomach, intestines, and colon would have been. Inferences can be made about a person’s diet should pollen or phytoliths be found in the samples. Isotopic testing is also planned for samples taken from the remains. Stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen can give clues regarding diet and location of European origin (read more about isotopic testing). Finally samples from the remains will be tested for lead. High levels of the metal indicate a person of means as they ate and drank from expensive lead-glazed ceramics and pewter vessels in a time before its toxicity was known.

While this section of the 1607 Burial Ground is open, the archaeologists are taking the opportunity to excavate and record some of the features found therein. Several postholes are being excavated, and by recording these into our GIS (Geographic Information System) software, we’ll be able to look for patterns that might indicate they belong to a nearby building, palisade, or fenceline. Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid found a decorative copper alloy martlet tack while excavating one of the postholes, a mythical legless bird that represented the fourth son in heraldry. The posthole may be associated with a wine cellar found in 2004 that dates to the late 1600s. The martlet tack is the third in the collection, with one on display in the Archaearium museum. Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch is investigating a feature comprised of clay, brick, and bone, possibly a heap of discarded building material. Some very fine copper wire was discovered in the feature. Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber found an intact projectile point, possibly a Morrow Mountain II point dating to over 6000 years ago.

In the Vault, Assistant Curator Lauren Stephens is mending a refined red bodied earthenware vessel found last year in the excavations south of the Archaearium. Likely a mug, the vessel is incomplete but there are enough mended pieces on one side to determine that it’s just over three inches tall. Although the handle is mostly missing, the lower terminus where it connects to the mug’s body is still attached. The vessel has been burned, with the fire changing the colors of the paste, glaze, and decoration. Just above the foot ring is a decorative beaded ring. This vessel was made between 1800 and 1850.

Associate Curator Janene Johnston continues her cataloging of artifacts from the Seawall excavations of 2021. These efforts will be included in reports that the archaeology and collections teams are working on to document the dig there. Janene cataloged a copper alloy leather ornament in the shape of a flower with additional stamped decoration. It is difficult to say for sure what it would have decorated but one possibility is horse furniture, what today we call horse tack. Another highlight of Janene’s cataloging this month are several glass beads of various colors and shapes. One of them has a red and white peppermint pattern with a blue core. Associate Curator Emma Derry is joining Janene in preparing artifacts for the Seawall excavations report. She is sorting through objects caught by a 1mm screen, looking for the tiniest artifacts and sorting them by type. Some of the artifacts she’s found this month include animal bones, bits of blue glass, beads, and copper straight pins.

Janene also continues her research on buttons in the collection. One of the avenues of study she focused on in October was attempting to determine if some of the wooden artifacts originally thought to be beads might instead be cores for thread wrapped buttons. Last year, Janene and Emma determined that the conical and domed wooden beads were almost certainly button cores and found a few threads still attached to one of the cores. However, the round beads are harder to determine the function of. Janene has spent time this month peering through a microscope, to see if magnification might yield any clues on these objects. Her efforts were rewarded when she found remnants of silver foils in one of the holes, indicating that at least one of the round wooden beads was indeed a button core. Several examples of such buttons can be found on Jamestown’s Wood and Thread Buttons page.

The conservation team inspects each artifact in the Archaearium museum on a regular basis as part of their duties. Their goal is to look for signs of deterioration in artifacts and treat them to prevent further decay. Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe spotted signs of the mending adhesive coming loose on a Virginia Indian jar that was on display there. The vessel, being globular-shaped and shell tempered, was found in a cellar/kitchen near the center of the fort. It has a spalled surface, revealing the individual clay coils that are the vessel’s building blocks. As conservation science is constantly advancing, the adhesive conservators use today (Paraloid B-72) is a different one than one our team used nearly 20 years ago when the jug went on display. For the sake of the vessel’s long-term health, Jo decided to disassemble the jug, remove the existing adhesive and mend it again using B-72. Because the team used a reversible adhesive, she was able to do this without damaging the vessel.

Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp only has six more layers of faunal material from the first Well to sort. The well was built in 1608 or 1609 while John Smith was governor, but by 1610 the well’s water turned bad and it was used as a trash pit. Over the past year, Magen has sorted, and with the help of volunteers counted, over 625,000 animal bones excavated from the feature, which speak to the diet of the colonists during the Starving Time winter of 1609-10. One of the highlights of the layer Magen is currently sorting, layer “J”, is a large number of shark teeth.

Collections Assistant Lindsay Bliss is sorting samples taken in 2023 from the Governor’s Well and floated in the summer months. Of particular interest in the light fraction, or material that floated to the surface during the flotation process, are seeds and other botanicals. Lindsay has identified many Blueberry seeds as well as possible amaranth and strawberry seeds, highlighting that the colonists were consuming locally available plant foods.

related images

- While some of the crew conduct excavations, other archaeologists combine building sections to construct the burial structure at the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch double checks her elevation inside of the 1607 Burial Ground structure.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis removes a feature cutting JR1454. It needed to be removed before excavations of the burial could continue.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber, Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis, and Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford build a roof for the burial structure at the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb, Staff Archeologist Gabriel Brown, and Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford install plastic sheeting on the burial structure at the 1607 Burial Ground.

- The burial structure at the 1607 Burial Ground

- The team trowels away at the upper layers of the 1607 Burial Ground.

- GSSI’s Peter Leach and Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley run a ground-penetrating radar survey of JR1850 inside the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Staff Archaeologists Ren Willis and Natalie Reid conduct a GPR survey of burial JR1454.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo and Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford conduct a ground-penetrating radar survey of JR1486.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis monitors the GPR results of one of the burials in the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Jamestown Rediscovery invited members of the Mount Vernon archaeological team to learn how we use ground-penetrating radar (GPR) during our burial excavations.

- Staff Archaeologists Natalie Reid and Ren Willis excavate JR1454 in the 1607 Burial Ground.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo and Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb excavate the top layers of the Smithfield burial.

- A projectile point found in the 1607 Burial Ground excavations

- A teardrop-shaped spangle found in the 1607 Burial Ground excavations. Modern sequins are similar in shape and purpose to spangles.

- A projectile point found in the 1607 Burial Ground excavations by Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber.

- The martlet tack shortly after its discovery by Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid.

- The new martlet tack found in a posthole during the 1607 Burial Ground excavations.

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith stands behind a number of soil samples taken from the 1607 Burial Ground. These will be processed by the flotation machine to help search for artifacts.

- Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch describes the 1607 Burial Ground excavations to visitors on an archaeology tour. Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith screens for artifacts at left.

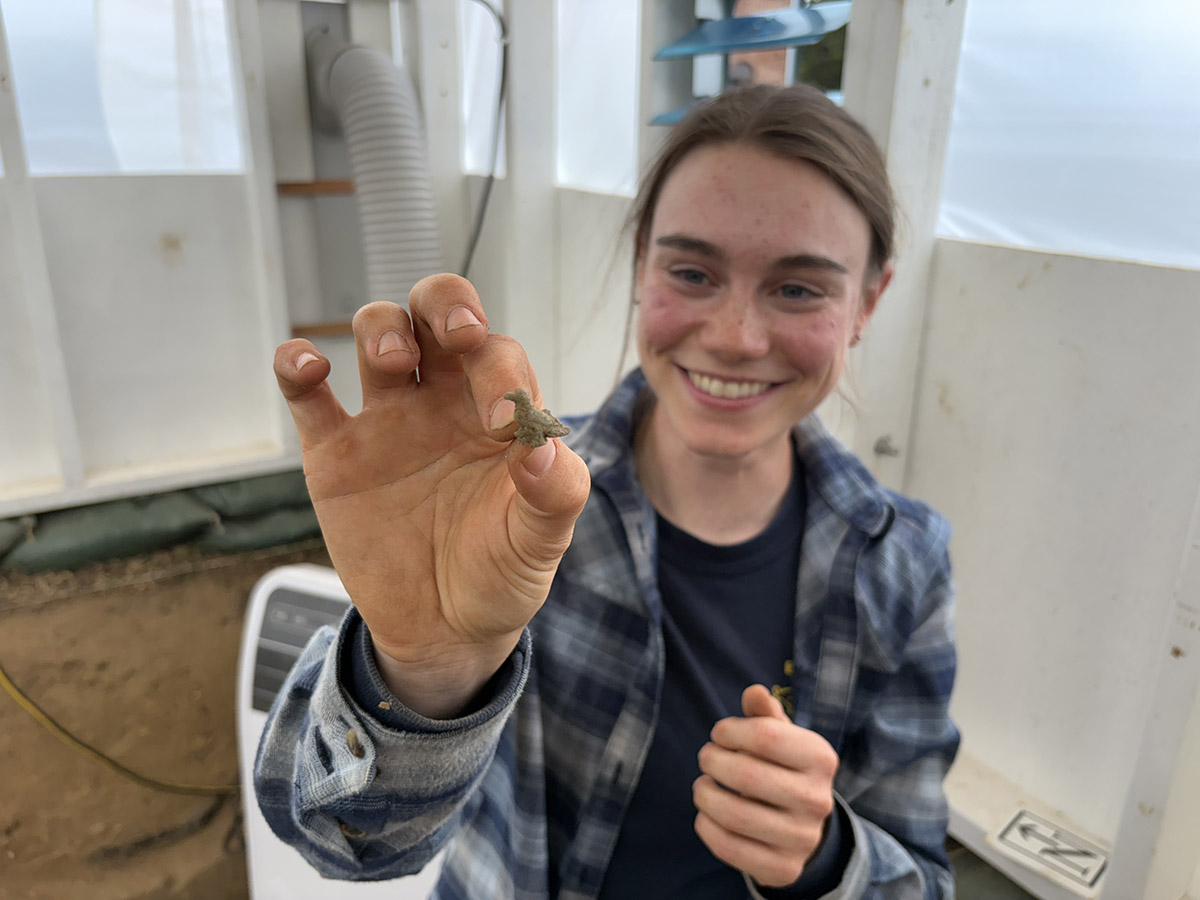

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith holds a gooseberry bead she found while screening soil from the 1607 Burial Ground.