October has been one of our busiest months this year! Our efforts were concentrated down at the Seawall, where we have been having problems with flooding. This flooding is caused by water runoff after heavy rains, compounded with river water seeping into the test units during higher tides. These challenges pushed us to find the answers we needed and wrap up the site before the site saw any significant damage could occur.

Continuing to excavate in the 17th-century layers in the Seawall Site test units, the team removed the partial brick foundation found last month. This brick foundation and a posthole uncovered during its excavation are likely associated with the property owned by merchant John White, whose warehouse was uncovered to the north from 1996-2002 during the initial excavations of James Fort’s eastern bulwark area. While it is still uncertain what this structure may be part of, the type of foundations and the posthole discovered match with those uncovered to the west and to the north during previous excavations.

Our focus at the Seawall is to find early 17th-century features associated with James Fort. These deposits will be buried deep here, and thus any overlying layers must be removed. The end of October was spent removing the remainder of the trash midden encountered in all three of our Seawall units, to hopefully expose James Fort features. Because of our continuing battle against water inundation in these units, we had to work extremely quickly. There are now three sump pumps keeping our test units dry, pumping out both water running downhill after rainfall as well as water trickling in during high tide. The longer these units are kept open, the longer we keep the archaeological resource in danger. Therefore, after uncovering any James Fort features we are going to backfill our test units until we can revisit a larger area with better water mitigation techniques in practice. In our final surge of activity, we excavated the remaining midden layers, leaving the labeled dirt outside of the units to waterscreen through consistently for the next couple of weeks.

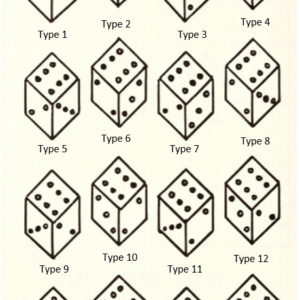

We have excavated other portions of this midden already and found a large number of artifacts dating to the second quarter of the 17th century. While we have been digging, our lab staff has begun to research some of the artifacts from the midden deposits, including a pair of bone dice. Dice can be categorized into several different types, based on the number placement on the side of the die as well as the orientation of the dots representing each number (see photo gallery for diagram). Out of the 80 dice we have total in the collection, 60 are Type 16. There are only three Type 3 dice: two of which come from this 2nd quarter 17th-century midden. Though excavated a number of years apart (1997 and 2021), both of these dice have the same style of simple concave drilled numbers, indicating that they could be a pair. Two other dice excavated from the midden (both Type 16) have a more elaborate (and more rare) “bulls-eye” style numbering and could be another pair.

While excavating the midden, we have had to deal with a variety of modern intrusions. One of our most exciting tasks at the Seawall this month was the removal of one of these modern features, a concrete septic tank probably installed in the 1930s. As satisfying as it was to get rid of this eyesore, our main goal was to see if any intact 17th-century features survived beneath the tank. If a feature was present, we would also be able to see its profile in the wall of the septic tank trench, providing us with a great deal of information. Early identification of layers in a profile provides a roadmap of how to dig a feature and gives us an understanding of how deep the feature extends into the ground.

While the prospect of gaining information is exciting, the team was also thrilled to bring out the big tools. For quick removal of the septic tank itself, we used a jackhammer and a sledgehammer. For the dirt, stones, and concrete fragments filling the interior of the tank, pickaxes and shovels were the most efficient way to go. During the removal process, the builder’s trench for the septic tank was left in place, protecting the adjacent 17th-century deposits from damage. These deposits (intact pieces of the midden and possible James Fort ditch) were also covered in a layer of sandbags and filter fabric to prevent any damage or contamination from falling septic tank debris and dirt. Though the septic tank is modern, we made sure to record every aspect of it before its removal by taking drone photos, making measurements, and even compiling a 3D photographic model.

Once the tank and its builder’s trench were completely removed, the team was in for a surprise: a James Fort-period ditch survived underneath the septic tank! Even more exciting, the profile showed different strata within this ditch. Although we were digging near the 18th-century shoreline, we now know that at least a few more feet of the 17th-century landscape survived next to the Seawall. In the future, we will be able to open up a larger excavation area to continue chasing this corner of the fort as far as we can. Since the West Bulwark trench was almost completely eroded away by the river, it is crucial that we excavate its sister to the east. This will help answer many questions that remain about James Fort, including the original shape of the East Bulwark as well as how it changed over time – especially after the fort was expanded to the east in 1608. Though we have the 1608 Zuñiga map depicting the 1607 James Fort, the actual archaeology can confirm or change our understanding of the early structure.

Despite most of the crew working at the Seawall, there are still exciting discoveries underway at our West Tower site. Last month, we began to uncover more of the fire deposits (a result of Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676) that we have been chasing throughout the area. While removing a layer of oyster shells and mortar debris related to the construction of the brick church tower in the 1680s, a large piece of burned plaster was uncovered directly atop the far west side of the burning. This plaster seals and is surrounded by the lighter red burn material visible in other patches across the unit, leading us to believe that the red material may be burned portions of the plaster’s scratch coat. As we excavate, multiple samples will be kept in order to compare this plaster to samples recovered during the Memorial Church excavations.

The finds at the West Tower site suggest that the original belfry from the 1617 Timber Frame Church was left intact until 1676. While the rest of the church was upgraded with brick in the 1630s and 1640s, the belfry remained unchanged. When the Bacon’s rebels boasted about burning down the church on September 19th, 1676, they were likely speaking about this wooden belfry, which would have fallen and smoldered in the area we are excavating. It then follows that all of the construction debris directly atop the burning would be related to the brick church tower, which was built in the 1680s directly after the rebellion. Analyzing this in situ plaster will allow us to confirm or reexamine our theory on how the churches on this site evolved over time.

As excavations continue at our North Tower site, the very tops of intact historic features are beginning to appear. Another section of the early James Fort-period pit is beginning to appear, as well as a possible portion of the 1607 east palisade wall. Originally, we left the eastern half of the test unit (JR4627) intact at the top of the historic landscaping layers. Now that we are on top of the early James Fort-period features, we can finish taking down the rest of the unit since we now have a good idea of the roadmap of the intact layers. We will also begin excavating a 5’ x 10’ test unit just to the west to better analyze the 1607 palisade. Since the palisade is running partially along the west edge of Unit JR4627, opening a slightly larger area will give us a better opportunity to study this section. With Seawall excavations coming to a close, we will soon be concentrating all of our efforts on our tower sites.

related images

- A diagram depicting the different types of dice. This diagram is adapted from the original by E.C. Potter (1992).

- A screenshot of our 3D model created of the Seawall site before beginning to remove the septic tank.

- The crew holds a piece of filter fabric over the septic tank so that they can cut it perfectly to size. Lying at the base of the septic tank, it will help to prevent the 20th-century soil (and possible artifacts) from contaminating intact 17th-century soil.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo swings the sledgehammer at the concrete as the septic tank removal begins.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley takes her turn with the jackhammer as we begin to remove the septic tank.

- Archaeologist Natalie Reid operates the jackhammer. After removing ~0.5’ of concrete, we switch back to removing dirt from within the septic tank.

- Staff Archaeologist Ryan Krank takes a turn with the sledgehammer, knocking out sections of the septic tank’s lower half.

- Midway through cleaning off the profiles impacted by the septic tank, the crew examines traces of the bulwark ditch visible in the western part of the profile.

- Staff Archaeologist Ryan Krank and Site Supervisor Anna work on removing the remainder of the midden and cleaning off the septic tank profile.

- Site Photographer Chuck Durfor takes record photos of the profile where the septic tank was removed. The yellow/grey clay to the left is intact subsoil, whereas the tannish grey dirt to the right, sloping down by the scales is our possible early bulwark ditch.

- Everybody pitches in to clean up the Seawall test units after the removal of the septic tank. Due to water inundation, we had to work as quickly as possible. After this cleaning pass, a round of record shots was taken.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford cleans where the base of the septic tank was in preparation for record photos. The yellow/grey clay in the top right is sterile subsoil; the mottled material to the left is 20th-century material related to the Seawall; and the grey stripe toward the bottom is the intact early bulwark ditch.

- A sherd of Spanish olive jar recovered from the James Fort bulwark ditch. In the background, the ditch is visible in the septic tank profile.

- Staff Archaeologist Ryan Krank carefully cleans the midden around the in situ milk pan.

- The milk pan after it was removed from the midden and cleaned off. A further two pieces were found in another midden section of the test unit after these two in situ sherds were excavated.

- A couple sherds of Bartmann jugs found within the midden down at the Seawall. Top: part of a medallion with a lion in the top right quadrant. Bottom: The base of the jug’s neck, with the bottom of a beard visible.

- A collection of redwares found while digging through the midden at the Seawall. Left: Four separate redwares. Right: Front and back of another separate redware found in the midden.

- A collection of artifacts recovered from the midden at the Seawall. Left: Green-glazed borderware sherd. Top right: Glass case bottle top. Bottom right: Glazed sherd of Midlands Purple.

- A drone record shot of the Seawall site after the removal of the septic tank and a full clean. There are still some remnants of the midden left in these record photos, however the possible early bulwark ditch is also visible cutting diagonally SW-NE through the eastern half of the units.

- One of our final record drone shots of the Seawall site after removing all of the midden from overtop of the possible bulwark ditch. Unfortunately, due to the high tides that day, we were unable to remove the sandbags and clean down where the septic tank was.

- The team works to create shade for the record drone photos. Consistent lighting is essential for archaeological record photographs.

- Our two active dig sites directly by the brick church tower. At the site right outside of the tower entrance, record photos are being taken of the oyster shell deposit.

- A deposit of oyster shell spread across the west side of the test unit. Likely a sign of lime production related to mixing the mortar during the construction of the brick church tower in the 1680s.

- A drone shot of the burning across Test Unit JR4593. To the left and above the utility line, the intact burned plaster is visible. Most of the post holes present likely belong to fencelines, both historic and modern.

- Two photos of a potential projectile point preform, found during excavations at the West Tower site.

- A drone shot of Test Unit JR4627. On the left is colonial topsoil and early 17th-century features; on the right is fill related to the construction of the brick church tower.

- A collection of artifacts found at the North Tower site this month. Top: Two different copper alloy book clasps found just above the early James Fort-period pit feature. Bottom: Two pieces of delft tiles excavated from the test unit.