When Jamestown Rediscovery began excavations in the 1906-07 Memorial Church, archaeologists hoped excavations would answer several questions regarding the three 17th century churches built in that location. One concerned the relationship between the 1617 Church and the brick church that replaced it in the mid-17th century. While the exposed foundations suggested that the brick foundations enclosed the 1617 church, evidence observed archaeologically contradicted a long-standing theory that later church was built while the 1617 church was still standing. Thanks to the archaeologists’ meticulous excavations, the brick foundations yielded new information that helped clarify written records and explain the inconsistent evidence.

Prior to the excavations, it was believed that the first brick church was built around the standing 1617 timber-frame building and that the parishioners continued to worship in the old church during the construction of the new one. To support this theory, the brick foundations enveloped most of the 1617 church’s cobblestone footing. However, excavations revealed that the western foundation of the brick church cut through the north foundation of the 1617 church in the northwestern corner, suggesting that the earlier timber-frame structure was already down when the brick foundation was built.

The mortar in the brick foundation yielded the final clues necessary to provide an explanation. The mortar in the north, south, and east brick foundations was significantly different from the mortar in the west foundation. A white- to gray-colored mortar was used in the north, south, and east foundations while a brown- or buff-colored mortar containing more sand was discovered in the west foundation. Close examination of all the foundations revealed that the contrasting foundations and mortars met in the north and south walls, approximately five feet east of the northwest and southwest corners.

The south wall junction was revealed after several feet of modern brick and cobbles were removed. These bricks and cobbles were installed by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA Preservation Virginia) in 1906-07 to show that the 1617 church foundation had once continued west. A burial associated with the brick church cut through and disturbed it. Once the modern feature was removed, it revealed two slightly misaligned foundations, with an approximately one-inch gap between them. This indicates that the south, north, and east walls of the brick church were constructed first and the west end was added later. Discovering that the west end was added last, suggests that the 1617 timber-framed church may have remained in use during the construction of much of the new church, and was likely torn down right before the west end was added.

Documents also support this sequence. According to a letter written by Governor Sir John Harvey to the Privy Council in London, many citizens contributed toward the “building of a brick church” in 1639. Another record suggests the new church remained incomplete until 1647 when Southwark Parish was “released from further tithes to the old Parish once they had paid their current taxes” for finishing the James City Parish church. Whether the new structure was complete enough to hold services is unknown, but it appears that the building was still under construction as late as 1647.

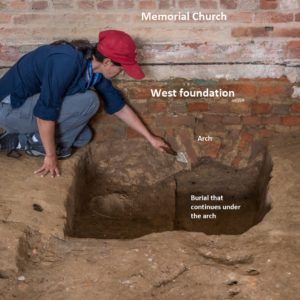

Excavations outside the church in December 2016 – February 2017 exposed an arch in the western foundation of the brick church at the southwest corner. Archaeologists originally thought that the arch was either structural or part of a drain; however, the explanation was unsatisfactory for two reasons. First, the arch was poorly constructed and no corresponding arch was found on the south side, ruling out its use as a structural support. Second, even though a pit feature uncovered on the interior was first believed to be a sump, there was no apparent reason for a drain in this location. When the pit was bisected, the arch’s function was discovered.

“I was about six inches into the fill, when I began to see a line of nails. This was the first indication that the feature wasn’t a sump, but that at least one burial was in this location,” explained Field Supervisor Bob Chartrand.

The nails were all that remained of a coffin that extended under the archway and beyond the western church foundation by an estimated three feet. The burial was undoubtedly associated with the 1617 church, and the arch was constructed to protect the grave. Significantly, since the burial extends beyond the west brick foundation, the western wall of the 1617 church also must be situated at least three to four feet farther to the west.

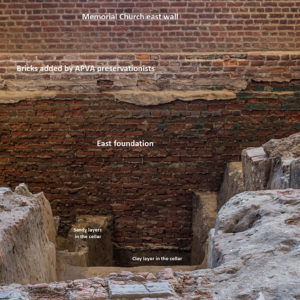

Excavations of the eastern end of the church also revealed new insights. The 1902 report of APVA excavators Mary Winder Garrett and Annie Galt states that the brick church’s eastern foundation was approximately two and a half feet deep on the northeast and southeast corners, but over six feet deep in the center. Rediscovery’s excavations confirmed their findings. Fortunately, Rediscovery’s previous excavations of James Fort period features helped explain this peculiar deep anomaly.

At first it was expected a burial vault would be discovered, but instead archaeologists found an early Fort-extension period cellar with loose, sand-filled layers at the depth of the east foundations’ corner. The team posits that to prevent the brick church foundation from settling into the backfilled cellar, the mason dug the builder’s trench down to a hard clay layer, deep in the cellar, to find a solid surface to support the wall. While not subsoil, the mason found the layer a sufficient base on which to build the brick foundation. This exceptionally overbuilt brick church wall indicates that there had been serious settling or slumping problems with the east wall of the 1617 Church The first church wall is believed to have stood a couple of feet to the west and stood on the back-filled cellar. By digging their builder’s trench deeper in the search of hard ground, the builders of the new church were hoping to ensure they would not have those same problems with settling.

related images

- Bob Chartrand maps the modern brick and cobblestone foundation added by Preservation Virginia in teh early 20th century, which was used to represent where the 1617 Church’s foundations once sat. Archaeologists removed this modern feature, which allowed them to learn more about the brick church’s foundation. They also identified a grave that disturbed the original 1617 foundation.

- After removing some modern bricks and cobblestones placed in the southwest corner of the church by the APVA, Les Jennings troweled the area below and found the outline of a grave associated with the brick church.

- Les Jennings points to the junction where the white and brown mortared brickwork meets in the south foundation of the brick church

- Junction between 1617 and brick church foundations

- Mary Anna Hartley trowels the grave that disturbed the western portion of the 1617 church’s cobblestone foundation. The confluence in the south foundation is just to the right of her left hand.

- Bob Chartrand points to the pit in front of the arch in the west foundation prior to excavation

- Mary Anna Hartley points to the space between the arch and the burial underneath it

- Intersection of brick and 1617 church foundations

- Notated features showing brick wall and excavated pit

- Features in the church southeast corner