During May, the Jamestown Rediscovery archaeology team made major progress in the 1906 Memorial Church as we continued to excavate the interior. Since we began in November 2016, our objective has been to remove overburden left from the 1901-1902 Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities’ (APVA) excavations in order to learn more about the three 17th-century churches that once stood in this location. These churches were in successive use between 1617 until the mid-18th century. After months of tests, Rediscovery archaeologists have acquired an in-depth understanding of the layers that seal the remains of all three colonial churches in order to confidently expand the excavation into the body of the Memorial Church.

The bricks that covered the Memorial Church’s floor are of early 20th-century manufacture, and many contain large gravel inclusions. Some were worn to about half of their original thickness, indicative of heavy visitor traffic through the years. The white marble blocks positioned in the brickwork throughout the church floor allegedly marked graves that were uncovered in 1901-1902. While this proved true in a few instances, their placement appeared inconsistent overall. Some of the blocks marked burials; others marked historic church elements, such as portions the original church floors.

Directly beneath the bricks was a bed of sand, which contained large pieces of gravel, brick fragments, and a few early 17th-century ceramic sherds. Much of the pottery appears water-worn, suggesting that the sand may have come from the nearby James River and that it included artifacts from eroding features on the river bank. It is probable that the sand was dug when the concrete seawall along the shoreline of APVA property was constructed.

Beneath the sand layer were intermediate areas of orange clay, sometimes with wagon wheel ruts visible throughout. This clay was probably laid during the construction of the Memorial Church, as all of the bricks for the building were likely brought in by wagon and required a thick stable surface to drive over.

The final layer consisted of a few inches of mixed brick, mortar, and plaster rubble that covered the evidence of the 17th-century churches. Scattered within the rubble were 20th-century machine cut nails that related to the construction of a short-lived barn, which post-dated the 1901-1902 excavations and pre-dated the Memorial Church.

Besides 20th-century nails, this layer contained a cast iron falconet shot, numerous handmade copper alloy straight pins, and small rodent bones. The straight pins may be shroud pins from disturbances of burials by the early 20th century excavators. On the north side of the church, a second-half-of-the-17th century iron carpenter’s chisel was recovered. A modern pencil lead was recovered, which was likely employed in note taking by the early APVA excavators.

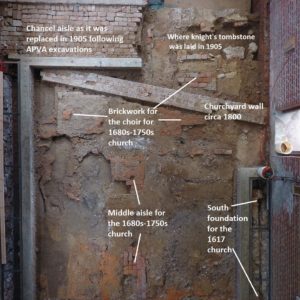

In addition to APVA reports about what was discovered of the churches, drawings of the church floor plan were made by John Tyler, Jr. and Robert Galt. These plans show brickwork for a wide chancel aisle and choir area just west of the chancel and a middle aisle with brickwork oriented east-west. Hoping to find remnants of these aisles, the Rediscovery team began excavating in the body of the church. Excavations revealed that they did uncover portions of the middle aisle; however, some of the brickwork is not oriented as the floor plan sketches illustrate. Much of aisle appears to have been patched together following 17th-century burials that were placed under the aisle. Current excavations are in keeping with Tyler’s report, in which he explained that much of the middle aisle was undercut by burials.

To the north of the aisle, Rediscovery archaeologists found no evidence of a brick floor, but discovered graves that cut through the surviving natural topsoil beneath the APVA backfill. To the south of the aisle, the team found clay and a possible floor joist cutting through it. More excavation in this area is necessary to determine if the clay is part of a church floor or if it is burial fill.

Finally, excavations under the Knight’s Tombstone, which was removed for conservation in April, revealed that there was not a burial aligned with the stone. Archaeologists were surprised to find only a small portion of one east-west oriented grave sealed by the stone. We found that in 1901-1902 APVA excavators also searched for a grave beneath the Knight’s Tombstone by digging a test below. Rediscovery archaeologists partially excavated their their backfill and found within the mixed soil a silver Spanish cob real!

Although quite worn, enough detail remained so that the coin could be identified. Dating 1664, it is a pillars-and-waves cob coin that was minted in Pitosi, Bolivia. Dan Gamble, Senior Conservator, professionally treated the coin. First, he removed the horn silver, or corrosion, very carefully under magnification in order to see the detail. A very sharp scalpel was employed to scrap off the corrosion without scratching the metal. Once the horn silver was removed, the oils from handling the coin were removed by soaking it in ethyl alcohol/ acetone degreaser. Finally, the coin was then coated using an acrylic known as B-72, and placed in our reference collections in the Vault.

Work in the church will resume in mid-June after the conclusion of the 2017 Jamestown Field School. This year, the field school will focus on the expansion of James Fort east and the transformation of the occupation from a fort into a town. As of the end of May, the students have begun four test units just east of the churchyard wall dated around 1800. Stay tuned for the many more exciting discoveries that are sure to surface in June!

related images

- Bruce McRoberts and Amy Baker removing bricks from the 1907 Memorial Church floor as the church site excavations expand to the west

- Bricks removed from the 1907 Memorial Church floor included this one with a dog pawprint

- Jamestown Rediscovery educator Amber Phelps checks out the removal of the latest section of the 1907 Memorial Church floor

- Features related to the 1907 Memorial Church construction

- This layer of clay was likely laid over the APVA backfill to serve as a protective working surface during the construction of the Memorial Church building in 1906-1907. Bricks for the building were likely brought in by wagon.

- This postcard shows the barn built by the APVA in 1902 to cover the church excavations

- Bruce McRoberts shows a visitor a 17th-century cannonball found in the 1901-02 backfill in the church.

- One of the many copper straightpins found in the church.

- A 20th-century pencil lead found in the APVA backfill layer.

- Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists uncover a portion of the middle aisle for the 1680’s church beneath the 1907 Memorial Church floor

- Kaitlyn Fitzgerald and Amy Baker uncover a portion of the middle aisle related to the last Jamestown church, dated 1680’s-1750’s

- Bob Chartrand trowels near a section of middle aisle related to the 1680’s-1750’s church

- Features within the Memorial Church

- Features surrounding the Knight’s tombstone location

- Pillar and wave type Spanish real, dated 1664.

- Conservator Dan Gamble uses a microscope and scalpel to carefully remove horn silver, a corrosion product, from a silver Spanish coin. The coin was found underneath the Knight’s Tombstone in backfill from APVA excavations beneath the stone.