In early June, Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists at the Angela Site completed excavations around a brick kiln they discovered in March. Based on the artifacts associated with the feature, the kiln likely produced the bricks used in the 1750s Ambler House construction. While only a portion of the kiln was exposed, the team found two test trenches dug by Civilian Conservation Corps excavators in the 1930s. A small test was placed in one to determine the depth of their trenches and whether or not any pre-kiln features survived. The trenches measured a depth of approximately one foot, making it unlikely that much from earlier would have survived the intrusion.

In addition to the kiln excavation, the team discovered a fence line and part of an undisturbed sub-floor pit in the corner of their excavation area. Both likely relate to the Ambler ownership. The pit contained artifacts dating to the 18th and early 19th centuries; among them are two East African ring cowrie shells that lay close to each other. The dorsal surfaces of both were removed, indicating that they were attached to clothing or worn as jewelry. Perhaps they belonged to enslaved Africans who lived on the Ambler plantation.

While the unit yielded no signs of Captain William Pierce’s house—where Angela lived and worked—the team hoped that expanding west might offer some leads. Director of Archaeology Dave Givens hypothesized that the location of “Back Street” was misidentified, and that instead of being on the riverside of the Ambler House, it may have been situated closer to the marsh on the other side of the site. If proven correct, Pierce’s lot orientation would change, and the 17th century burials discovered in 2018, would have been placed to the rear, rather than in front, of the Pierce property. To investigate his theory, archaeologists began a ground penetrating radar survey of the slope. Concurrently, a new unit along a present ridge near Structure 59 was opened for exploration.

At the Fort site, Rediscovery began excavating new units around the 1907 brick Memorial Church to answer more questions regarding the 1617 church and the two 17th century brick churches. At the 17th century church tower’s southeastern corner, a unit was opened to search for evidence of the 1617 Church’s south foundation that continued through that area. Archaeologists predicted that evidence would be scant, however they hoped to find some of the early cobblestone and clay foundation in the builder’s trench of the later brick church tower. As expected, the early foundation did not survive the tower’s construction. However, archaeologists did unearth plaster and bits of yellow clay from the 1617 church, as well as a couple of small cobblestones that may have been used in the foundation. In addition to the scatter of early 17th-century artifacts, a ca. 1660-1680 pewter pipe tamper recovered from the builder’s trench lends support to the belief that the church tower was constructed later in the 17th century. The builder’s trench also revealed an exciting discovery. Despite the extensive intrusion of a concrete buttress foundation for the Memorial Church—the last few inches of 1607 James Fort’s east palisade trench survived in profile near the bottom of the builder’s trench!

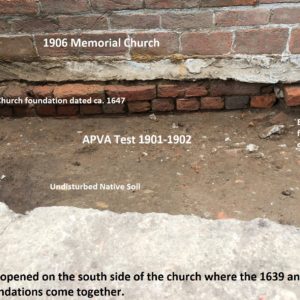

Around the corner of the Memorial Church’s southwest buttress, archaeologists also opened a test unit searching for evidence of a south entrance for the 1617 church. Excavations inside the church last year had revealed that the brick church’s walls were built in two phases. Current theories suggest that the eastern end of the brick church began in 1639 as recorded, but was left incomplete until sometime around 1647, when the western end was added. In the interim, the earlier timber-frame church remained standing for use during services. This new unit was located at the junction of the east and west brick church foundations, which a suggested that the first phase of construction stopped to leave access to a south west entrance. While there was no definitive evidence of a door, archaeologists did uncover an interesting shallow feature filled with 1617 church interior plaster fragments—some of them quite large. Further research is necessary to determine to what that feature might relate.

In the Jamestown Rediscovery lab, Senior Conservator Dan Gamble inspected turned window lead—lead for holding glass panes in place—recovered during the 2018 Memorial Church excavations. Window lead interiors sometimes bear the manufacturer’s initials or dates of the device that was used to make them. Since X-rays cannot penetrate lead, conservators must open turned lead manually to check for initials and dates. As Gamble explained, “Window leads are the only artifact that we ever manipulate after they come into the lab. Because this information is invaluable for indicating the age of a structure, the ends justify the means.”

Gamble began the process by soaking the lead in an ethanol solution of EDTA for three hours. The solution removed the precipitated salts that occurred while it was buried and improved pliability of the metal. Then, he delicately completed the operation using a microscope. Fortunately, the recovered lead was stamped and legibly read “1671 * W*W*.” The lead likely related to the Church rebuilt following Bacon’s Rebellion or it could have been a repair to the windows in the 1640s church.

related images

- Angie Tomasura and Charde Reid map features found around a brick kiln at the Angela Site

- Map of CCC trench

- Rediscovery archaeologists point to postholes likely related to the Ambler property. Behind the team are the remnants of a brick kiln and CCC test trenches through the site.

- Archaeologist Delaney Hunter cleans bricks associated with the kiln

- One of two cowrie shells found in a pit feature likely related to the Ambler property and dated to the 18th century

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand runs GPR behind the Ambler House at the Angela Site

- Rediscovery archaeologists open a new unit at the Angela Site looking for evidence of William Pierce’s house

- Rediscovery archaeologists open a new unit at the Angela Site looking for evidence of William Pierce’s house

- Anna Shackelford and Nicole Roenicke draw profiles in the tower unit

- Test at the SE corner of the church tower

- Meaghan Harrington and Anna Shackelford draw the profile of the church tower builder’s trench

- Memorial Church features

- Test unit opened on the south side of the church where the 1639 and 1647 brick foundations come together

- Archaeologist Kaitlyn Fitzgerald uncovering the 17th-century foundations for the Brick Church during the summer of 2019.

- Feature full of 1617 church wall plaster found in the south unit

- Supervisors fill out paperwork south of the church

- Window lead found during the church excavations in 2018

- Senior conservator Dan Gamble prepares to examine a window lead piece found during the church excavations

- Gamble pours an ethanol solution of EDTA to soak the window lead

- Conservator Dan Gamble opens the window lead to check for a manufacture date

- The opened window lead is stamped with the date 1671