Jamestown Rediscovery was excited to host both sessions of their Archaeological Kids Camp this month! Kids Camp Coordinator Natalie Reid and the archaeology team led the campers in the excavation of squares downslope from Statehouse Ridge in front of the Archaearium. Continuing the work begun by the field school students last month, the team seeks to define the southern boundary of a cemetery identified on the Statehouse ridge in the 1950s. Rediscovery archaeologists excavated many burials here in the early 2000s while preparing for the construction of the Museum. They determined that the burials likely date to ca. 1610s-1640s.

In June the team and field school students discovered the outlines of nine burials here, and based on their size, two of them likely belong to juveniles. Unlike the densely concentrated burials found on the top of the ridge to the north, these newly discovered graves are more widely spaced from one another. The campers are helping excavate exploratory squares to the south of the original line of excavations conducted by the field school students, looking for undisturbed area that might indicate the end of the burial ground has been reached.

Heading south from the Archaearium, Statehouse Ridge gives way to Smithfield, a low-lying field area between the Museum and 1861 Confederate Fort Pocahontas, and the elevation gradually drops a few feet. The team has witnessed more frequent flooding in Smithfield during the last two decades and their ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys of the field show that the ground water is often only about 2 feet below the surface.

GPR prospecting of the newly found graves indicates that they are only one-and-a-half to two-and-a-half feet deep. This means that in low-lying areas like Smithfield, human remains are often submerged from surface and/or groundwater flooding. As water levels fluctuate in Smithfield, these remains will alternate between wet and dry conditions, which causes bone to rapidly deteriorate. Currently, the team plans to excavate one of the burials here in the fall in order to examine and evaluate the condition of the remains. The status of the remains here — if they are intact, deteriorating, or already dissolved — will help determine future excavation plans for Smithfield and other areas threatened by flooding.

Aside from burials, the staff, students, and campers working near the Archaearium have uncovered what initially appears to be an early 17th-century building. The team is expanding the excavations here to uncover more of this possible structure, and to definitively date the features associated with it. If our assessment is correct, this building is very similar to Structure 187, an early structure in the center of James Fort.

In between Kids Camps, Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis focused on finishing the excavation of a subfloor pit in the field just north of 1607 James Fort. This pit is the second the team has tested in a line of seven pits identified by a 2019-ground penetrating radar survey. Similar to the previous subfloor pit tested to the west, this second pit has narrow steps or shelves carved into its sides and it tapers to a squared bottom. Interestingly, the team found two features associated with this second pit: a single posthole at its southeastern corner and a scattering of ash/charcoal to the southwest, which appears to be the remnants of hearth debris. The locations of the posthole and concentration of ash/charcoal are identical to those found around the previously-examined subfloor pit to the west. This repeated pattern confirms the pits are root cellars within small structures.

The subfloor pits appear to be early, and are devoid of artifacts except for one or two beads and some animal bones. A lack of artifacts can actually point to an early date for a feature, indicating that it was located in an area without prior occupation and thus without much occasion for humans to drop or discard things. Excavations and GPR have discovered several of these pits, three of which have been partially or fully exposed by archaeologists: the two worked on recently, and a third uncovered in the early 2000s. The two recently-dug pits are eighteen feet apart, while the third is thirty-six feet farther east. If this pattern holds true, another subfloor pit should be located in between. In this linked diagram, the red squares indicate the archaeologically-examined pits, with the yellow square marking where the a fourth one should be. Future excavations are planned to ground truth the other GPR-identified pits

In addition to putting their trowels and shovels to good use, the campers also learned to screen the dirt they excavated to search for artifacts. They conducted GPR surveys just outside the Ed Shed, in the Church Tower, and in the field north of James Fort. The Jamestown archaeologists instructed the campers in the use of GPR machines and also taught them how to analyze the resultant data to look for features. The campers took a break from the heat and headed to the lab to process the artifacts found by the field school students and archaeologists south of the Archaearium last month. The curatorial staff instructed them in cleaning, identifying, and sorting the artifacts.

While perusing the archaeological collection in the Vault’s Archive, the curatorial staff found several sherds of a thin, red-bodied slipware probably belonging to one of two fragmentary tankards housed in the Vault Reference Collection. The vessels likely were made in the London-based pottery of John Dwight, a pioneer of English salt-glazed stoneware and other wares. Dwight’s successful production of stoneware ceramics in the 1670s offered England an alternative to the Frechen-based (a town in modern western Germany) salt-glazed stoneware which dominated the European market since the 1500s. The ca. 1680-1700 slipware sherds likely are part of two tankards, made from red clay and spattered with splashes of tin-, manganese-, and copper-oxides. Similar vessels have been found on other nearby sites, including New Town just to the east of the 1607 fort site, and in James City County on the Drummond plantation on the Governor’s Land and at Neck-of-Land. This specific type, with its spatters and tight cordoning, although likely produced in London, is a rarity in England itself. It seems the vast majority of these vessels were exported across the Atlantic. These “new” sherds were excavated from the Confederate fort in the first decade of the 2000s.

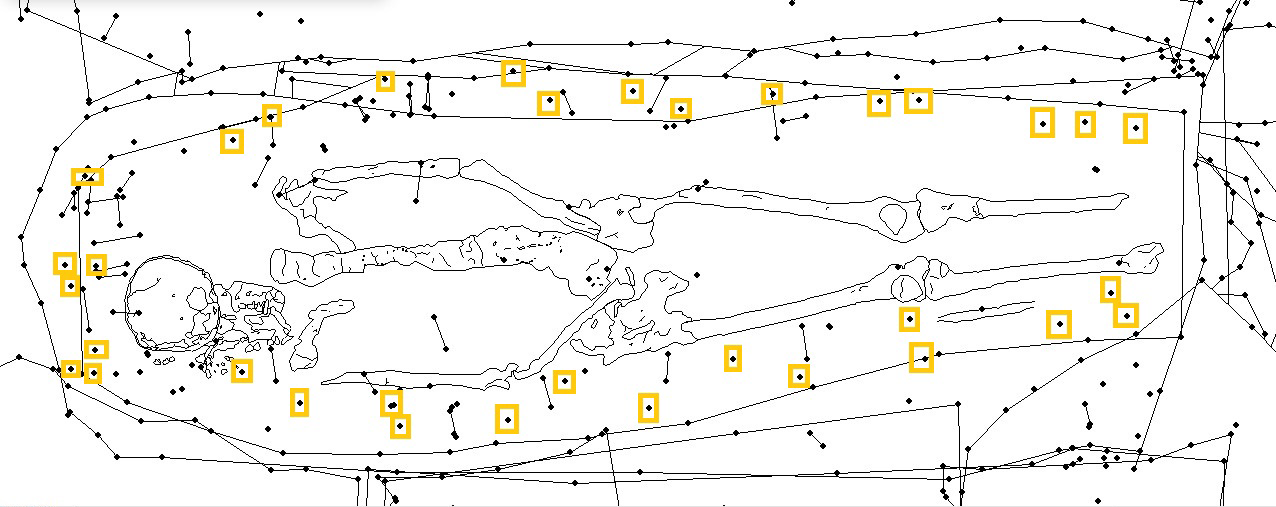

Senior Conservator Dan Gamble is conserving and researching coffin hardware, iron pieces that served as decorative elements for the coffins of those with the means to afford it. Dan is currently conserving hardware from a burial found in the southern part of the chancel of the third church. The burial was oriented in an east/west fashion (pointing toward Jerusalem) as was the custom in the 1600s. It belonged to a male, likely in his 20s at the time of death. Approximately 30 decorative iron pieces were excavated from the burial in 2017/18 by Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley and Archaeologist Bob Chartrand. The decorative hardware was dipped in tin to make it shine. Dan used an air abrader to gently remove corrosion during the conservation process.

Now that the hardware has been conserved, the research may begin. Dan and Mary Anna are working together to figure out what the hardware originally looked like and when it dates to. Their initial finds suggest that decorative hardware was relatively rare in much of the 17th century, but it became more popular later in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Dan and Mary Anna are currently looking through literature, archaeological reports and museum collections for contemporary examples that might help flesh out the forms and any possible symbolism behind its shapes and disposition. When Mary Anna excavated the burial, she found the coffin’s wood had all rotted away, leaving only the decorative hardware and nails behind. The locations of these pieces were recorded prior to their removal to the lab for conservation. This data will help Dan and Mary Anna figuratively piece together the coffin as they work together on this research.

Senior Curator Merry Outlaw is organizing and selecting representative delftware vessels— Dutch or English tin-glazed earthware — for the Reference Collection. The pottery type was first made in northern Europe by Italian immigrants to Antwerp but then spread throughout the Low Countries and eventually to England by Dutch potters (of Italian descent) immigrating there. Because the fabric and glaze was often sourced from the same locations in the early 17th century, determining whether the objects are English-made or Dutch-made can be very difficult. The ware type gets its name later in the 17th century from the town Delft, Netherlands, where much of the pottery was made. Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens is assisting in the process by using the pXRF (portable X-ray Fluorescence) machine to test one of the Delft dishes in the Jamestown collection. She is trying to determine if its exterior glaze is tin-based or lead-based. This non-destructive process has become an invaluable tool to the collections team to aid in both conservation and curation as knowing the chemical makeup of an artifact can be instructive for both fields. If the pXRF results indicate the exterior glaze is primarily lead-based, then the dish will technically be classified as majolica.

Conservation Intern Amanda Arcidiacono has completed her internship with Jamestown Rediscovery. She spent 8 weeks with us, conserving over 30 window leads. Before they were conserved, Amanda and Senior Curator Leah Stricker undertook the conservation prioritization process, in which artifacts were prioritized for conservation based on several factors. These include artifact uniqueness, context or feature in which it was found, artifact stability, time involved in the conservation, and material. Amanda also took record photographs of over 100 leads. Leah is now entering the artifact information into our collections database. Several of the leads bear dates and maker’s marks but none were unique to the collection. We are grateful to Amanda for her invaluable contribution to the conservation of Jamestown’s window lead collection.

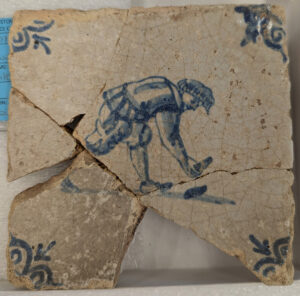

Thanks to the efforts of the field school students and staff the mending process for the Delft tiles is nearing completion. Over 100 mends have been made over the past couple of months and we have at a minimum 85 individual tiles. Most of the tiles include images of people – many of them are soldiers equipped with swords, armor, muskets, or pikes. Other tiles show tradesmen or figures who appear to just be walking or running, and some figures appear to be playing games, like the tile at left that possibly shows a man playing quoits. Quoits is a game similar to horseshoes where the players throw a ring in an attempt to land it over or near a spike. Another one of the favorites in the collection is a tightrope walker!

Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp is almost done with sorting the smallest faunal material found in context 2718W, a layer of the fort’s first well that was filled with over 100,000 animal bones. Next she will move on to layer “N” of the well, nicknamed the “John Smith Well” because he ordered its construction in late 1608 or early 1609. Interns and visitors in the Ed Shed started the sorting process of material from layer N this summer, enabling further analysis by Magen, and contract Zooarchaeologists Stephen Atkins and Susan Andrews.

related images

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid leads a tour of Jamestown on the first day of Kids Camp.

- Field school student Grace Blondin-Kissel helps a camper push screened soil to the dirt pile.

- A camper excavates in one of the squares south of the Archaearium.

- A camper scrapes away in the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- A camper digging in one of the squares just south of the Archaearium.

- Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb supervises a camper as he screens for artifacts.

- Campers screening soil from the excavations for artifacts

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid supervises screening during Kids Camp.

- A camper shares an artifact she found while screening.

- A camper holds a clay pipe bowl he found during his excavations.

- Campers holding a European pipe they found in the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- Campers conduct a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey northeast of the fort with guidance from Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo teaches campers how to use the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) machine.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid leads a question and answer session at the conclusion of the first session of Kids Camp.

- Campers from the first session share the artifacts they found with their families.

- A page from a camper’s field journal

- 2024 Kids Camp Session 1

- Kids Camp Session 2

- Coffin hardware found with a burial in the southern part of the chancel of Jamestown’s third church.

- Conservation Intern Amanda Arcidiacono conserves a window lead.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp’s sorting tray filled with animal remains from the fort’s first well.