Thanks to precise and patient trowel work by staff and intern archaeologists, the east churchyard site opened by the 2017 Jamestown Field School students finally yielded its findings this July. The area contained over 30 burials and several planting furrows related to early farming at James Fort in 1607-1608.

The thickest layers of overburden in the area related to two phases of landscaping completed by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA) in the early 20th century. Removal of these modern layers revealed intact colonial topsoil, which was trampled and mixed over the surface of the graves. It appears that when the colonists were burying people in the churchyard, the original ground level was close to this elevation. Units excavated near here in 2013 required dozens of trowel cleanings to identify the graves and their relationship to one another, and to reveal features predating the churchyard.

“With each pass of the trowel, the burial shafts became more defined and it was apparent that the churchyard had extended outside the 20th century brick wall. Also, the identification of more planting furrows indicates that the boundaries of James Fort’s earliest agricultural fields remain undetermined,” remarked Field Supervisor Mary Anna Hartley.

While the team did not uncover evidence of structures predating the burials, they did discover several early 17th-century artifacts that suggest that a 17th-century building site may be nearby. Artifacts scattered throughout the intact colonial topsoil included a bone handle knife, a copper alloy Catholic medallion, an iron counter weight for a sword, an iron scabbard chape, and dozens of fragments of scrap copper.

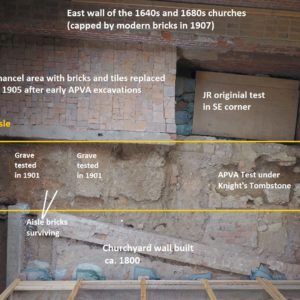

Indicating that there were three different burial periods, the burials were in at least three different east-west orientations. Many are perpendicular to the Memorial Church, which sits directly upon the foundations of the 1640s and 1680s churches. Others are line up with the c. 1800 brick churchyard wall, which is slightly misaligned with the church. Curiously, a few graves appear to be perpendicular to the 1607 James Fort’s east palisade wall. Once all of the burials are mapped, their orientations and relationships with graves discovered in other areas of the church will help to determine when they were interred.

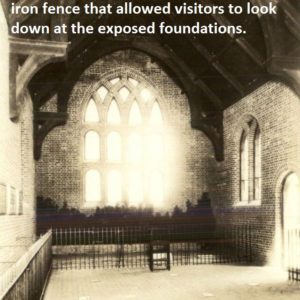

The interior of the Memorial Church has also been abuzz with activity in July. Jamestown field school students completed the removal of the west half of the floor and archaeologists tested features previously dug and recorded by the early-20th century APVA preservationists. Simultaneously, conservator Michael Lavin removed the concrete curbs that lined the north and south walls of the Memorial Church since its construction. These curbs once supported an iron fence that allowed visitors to view the exposed foundations of the earlier churches. The iron fence was later replaced with ground level glass panels through which, for the past few decades, visitors could see the 17th century foundations.

After the curbs were removed, archaeologists re-excavated the original trench along the south wall of the 1640s church. It was within this trench that Mary Jeffery Galt, APVA founder, records digging “with [her] own hands” in 1897, and a silver dime of that date was recovered in the backfill. Galt wrote that in the trench she found an inner wall with cobblestones, clay, and brickwork of a church pre-dating the 1640s church. She proposed that the wall related to the 1617 church that was constructed when Samuel Argall was governor. Comparable to Rediscovery’s findings along the north wall of the 1617 church, the team located grave shafts cutting through parts of the cobblestone wall. In contrast to the north wall discoveries, more of the south wall survived the later burial intrusions.

After removal of the Memorial Church construction backfill, the outlines of previous tests became visible. Included in Galt’s report is a description of the test in the southwest corner. She wrote: “On the 7th of June we discovered in the southwest corner of the church floor the 6 x 6 compartment in a frail foundation, the two spades and grubbing hoe of the sexton….” Rediscovery archaeologists began re-excavating the southwest corner test this month, and curators and conservators in the lab began re-examining the aforementioned tools, which are in Rediscovery’s archaeological collections. Watch for more developments about this compartment and its contents.

Finally, the modern brickwork in the north half of the chancel aisle was removed to reveal the discoveries made in that area more than one hundred years ago. A small marble block incised “No. 2” was placed there by the APVA excavators. Unfortunately, documents about the block and its meaning have never been found. Rediscovery archaeologists and historians predicted that it and others like it throughout the 20th-century tilework floor marked burials that were found during the APVA excavations.

The theory proved correct, for when the marble block was removed, a backfilled burial shaft was exposed. In addition to revealing this shaft, the Rediscovery team uncovered another APVA-tested burial shaft and discovered bricks from the original chancel aisle. Before continuing excavations in the chancel aisle, the staff anticipates that they will completely remove the modern tilework and concrete from the chancel during the month of August. Check on our progress in the August dig update.

related images

- Aerial view of Summer 2017 excavation units

- It took archaeologists a couple of weeks to complete the east churchyard site. They uncovered over 30 grave shafts and several planting furrows. They also found modern postholes related to fences that were placed around the chuch and churchyard in the late 19th century in order to protect the site from vandalism.

- Aerial view of planting furrows and burial shafts

- A bone-handled knife found east of the churchyard wall

- Michelle Carpenter holds a small religious medallion found east of the churchyard wall

- The copper alloy religious medallion found east of the churchyard wall

- Iron chape for a scabbard found at the churchyard site

- The 1907 Memorial Church in the early 20th century. This postcard shows the iron fence that allowed visitors to look down at the exposed foundations.

- Field school student Katie Dowling cleans a layer of backfill in the 1907 Memorial Church, revealing an early 20th-century test unit in the southwest corner dug by APVA excavators.

- Field school students Amber Freeman and Jack Beimler remove the last few inches of rubble from the construction of the 1907 Memorial Church. A majority of the artifacts found were machine-cut nails, but the students also recovered the neck to a wine bottle likely discarded by the workers.

- Fragment of an early 20th-century wine bottle, which was likely dropped by one of the workers constructing the 1907 Memorial Church.

- Features inside the Memorial Church

- The trench dug by APVA founder Mary Jeffrey Galt in 1897, where the south wall of the 1617 church was discovered.

- Maddy Bassett removes 20th-century backfill from the APVA test trench dug in 1897. Along the way, she is exposing portions of teh 1617 church’s south foundation.

- This 1897 Barber Dime was found in modern rubble that filled the trench along the 1617 church’s south foundation. This foundation is described by APVA founder Mary Jeffery Galt, who wrote, “In the year 1897, I dug with my own hands deep inside of the south wall of the [1640’s] church and discovered the little inner wall composed of large bricks and cobbles.”

- Maddy Bassett and Mary Anna Hartley remove backfill from the trench in which Mary Jeffery Galt found the south foundation for the 1617 church during the 1897 excavations.

- Excavated features within the Memorial Church

- This marble block in the chancel aisle marks a grave that was found and tested by the APVA excavators in 1901.

- Kaitlyn Fitzgerald removes brickwork replaced in 1905 in the north half of the chancel aisle.

- Intern archaeologist Leah Stricker removes the last few inches of modern backfill placed over the chancel aisle after the completion of 1901-1902 excavations.