Not too far from the Memorial Church, where Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists are looking for the remains of the church in which the first General Assembly convened in 1619, a second team of archaeologists is focused on a different—and equally dramatic—story of our nation’s beginnings. August of 1619 marked the arrival of more than 20 enslaved Africans to Virginia on the ships Treasurer and White Lion. One of them was an Angolan woman named Angela.

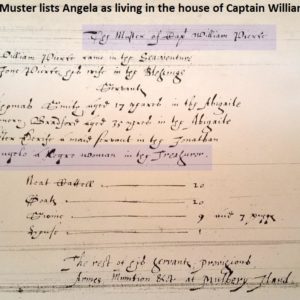

Rediscovery archaeologists began digging in May 2017 with funding from the National Park Service with specific regard to addressing race and diversity at early Jamestown. Although the first Africans were dispersed within the colony, records indicate that Angela was listed as living with prominent planter and merchant Captain William Pierce. Traces of Pierce’s home site—thought to be located on a seven-acre lot in the colonial town—was lost to nearly four centuries of subsequent occupation.

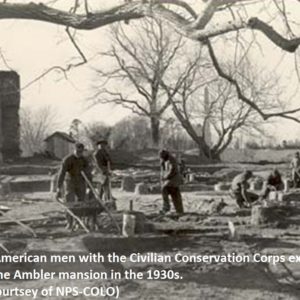

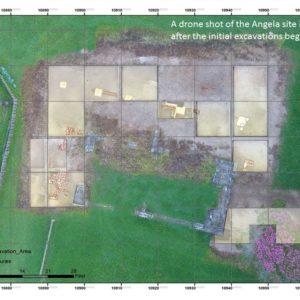

In collaboration with the National Park Service, Jamestown Rediscovery is excavating parts of Pierce’s original property, hoping to define the physical and cultural landscape in which Angela lived and worked. It’s not a simple task; the site, which lies just 120 feet to the east of the ruins of the 18th-century Ambler mansion, was excavated and backfilled in the early 1930s. Park archaeologists—many of whom were segregated, African-American CCC workers—discovered the remains of three superimposed brick structures associated with subsequent occupation of the site.

“We are digging in James Cittie,” said Project Archaeologist David Givens. “It’s a needle in a stack of needles.” The archaeologists are confident that the location where Angela lived and worked is under the centuries of occupation. “We spent half of the year in the archives pouring over the history, previous archaeology, and the artifacts,” said Givens. “Now we’re out of the library and into the field.”

The first goal of the team was to re-excavate the archaeology from 1934 and closely study the iterations of structures, one on top of the other. Almost immediately the team found evidence of a post-in-ground structure that appears to pre-date the second quarter of the 17th century. Additionally, much like the CCC workers, the Rediscovery team has found a smattering of early 17th-century artifacts dating to the Pierce tenancy.

“Although there is a considerable amount of later 17th- and 18th- century artifacts,” said Curator of Collections Merry Outlaw, “we are seeing an intriguing mix of early 17th- century European and locally made ceramics and tobacco pipes.”

The current Jamestown Rediscovery excavations that began in 2017 and are expected to continue for three years. Goals for the project go well beyond locating the Pierce home site, identifying its occupants, and determining how the site evolved. They hope to intensively examine Angela’s impact on the Pierce family—the earliest known record of an enslaved African living in a household in English North America—to learn more about race, ethnicity, and inequality across the plantation landscape of 17th-century Virginia.

“Not only is our work exploring the context of African enslavement in English North America,” said Givens, “but the archaeology at the site allows us to engage the public in a discussion of how diverse our Nation’s beginnings really were.”

Angela was one of the first Africans to experience the New World, living and working in the Pierce household for at least five years. The clues that she left behind in the archaeological record—along with subsequent centuries of Virginia Indian, African, and English—will add to the emerging narrative of diversity at Jamestown as well as scholarship on the ethnic and racial encounters that have been among the defining characteristics of American society, past and present.