Despite being slowed by rain and snow, Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists at the Angela Site spent the end of November and December opening two additional 5’ x 5’ units on the southern boundary of the dig site, near the National Park Service’s gravel lane. Aided by some dedicated Rediscovery volunteers, the team found another area previously investigated by workers with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in the 1930s. One of these CCC units cut the south end of the large pit feature found last summer, which might be part of the period of Ambler family occupation. They also investigated a posthole possibly related a structure built on the property by William Sherwood after Bacon’s Rebellion. The posthole yielded a fragment of Portuguese faience, which dates to Sherwood’s occupation.

In the church, archaeologists and conservators backfilled the excavation site in preparation for the reconstruction of the new floor in 2019. The team plans to have the church rebuilt based on the archaeological findings and an exhibit installed by early next summer. One of the last areas to excavate is along the 1617 church’s south cobblestone foundation, which will remain open as a portal for visitors to see below the floor. Once archaeologists finish the last small section within the portal, contractors will install concrete to support three glass panes. The glass will allow visitors a window to see archaeological evidence beneath the floor. After this is complete, archaeologists are hoping to start excavations in Jamestown’s iconic church tower in January.

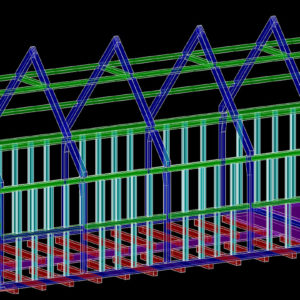

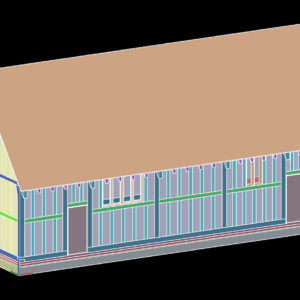

Behind the scenes, the Jamestown Rediscovery digital team has been working on a 3D model of the 1617 church as part of the Virtual Fort project. When applied to historical landscapes, 3D modeling uses sophisticated computer software to re-create buildings, furniture, objects, and the environment to help visualize past sites. The Jamestown Rediscovery team uses a two-stage modeling process. The first is the creation of a “research model” that accurately reflects a building or object’s structure and geometry. The second stage involves adding textures, furnishings, landscape elements, and lighting to produce photo-realistic views.

The 1617 church is being virtually reconstructed to 1619 when the General Assembly first met. The building’s research model, which is nearly finished, is based on archaeological evidence, historical sources, and surviving comparable 17th-century English churches. While some of its features, such as window placement and interior furnishings, remain speculative, the virtual version will replicate the feel of the church, both inside and out. And, unlike a physical model, the computer model can be easily updated if new information comes to light. See some of the renders of the research model below and stay tuned for further updates on the progress.

- Bruce McRoberts and Lee McBee examine artifacts found at the Angela Site near the brick hearth

- Rediscovery volunteers Howie, Scott, Penny, Joe, Larry, and Kevin with archaeologist Delaney Hunter at the Angela Site

- Volunteers work on two units at the Angela Site

- Lee McBee fills out paperwork at the Angela Site

- A large posthole likely associated with a structure built by William Sherwood

- Merry Outlaw compares a sherd of Portuguese faience with a fragment found in posthole at the Angela Site found by Bruce McRoberts

- Anna Shackelford excavates in the area where a glass portal will be installed in the new church floor

- Les Jennings screens soil from the last area of the church excavations

- Building design software is used to recreate the church’s framing to replicate how it would have been constructed in the 17th century

- Once the team feels that the building’s structure accurately reflects the available evidence, they begin filling in other architectural elements such as doors and windows. The next step is to apply textures like wood and plaster to create photorealistic views of the what the church looked like 400 years ago.

- The team meets periodically to review the model. Rebuilding the structure in 3d space can help to interpret some of the archaeological findings. If the archaeological evidence does not provide information on how something would have been built, then the team bases things on similar surviving contemporary structures.