August was one of our busiest months this summer. The archaeology and laboratory teams both have several exciting projects in process, and the teams are working together on our ongoing well excavation.

Led by Director of Archaeology David Givens, The archaeologists are almost to the water table in the Governor’s Well excavations and things are getting a bit muddy. They’re carefully excavating the builder’s trench and the interior fill of the brick well shaft, so that they can understand the stratigraphy within the feature before proceeding into the water table. Each bucketful of soil excavated is hoisted to the surface above, where it is screened for artifacts. Samples of soil will also be set aside to undergo flotation, a process that uses water to separate artifacts based on density. Flotation can be particularly effective in finding organic material such as seeds and bits of wood. The entire team, including Archaeological Intern Eleanor Robb, has lent a hand (and a trowel) with the excavations down in the well. Senior Staff Archaeologist and Staff Photographer Dr. Chuck Durfor often is down in the well to photograph each step of the process. A projectile point and a large sherd of Virginia Indian pottery were found in the excavations of the well’s builder’s trench this month. Visitors can be part of the moment of discovery by watching the well excavations in person or on the Well Cam on the Governor’s Well webpage.

In the field north of the fort, Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley is excavating a subfloor pit, one of many spaced at regular 18-foot intervals in an east/west line. This month Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford has been assisting with this complex and somewhat mysterious feature. It has been largely devoid of artifacts save for a few animal bones near the surface, making identifying or dating the feature difficult. It is a couple of feet deep at its deepest, though Mary Anna points out that a foot or two of soil has been lost to erosion and farming since the early 17th century. The feature appears to have been filled in deliberately (all at once) rather than through neglect. Mary Anna has fully excavated the eastern half and the feature appears to have two levels. One theory is that the feature was a root cellar, which was originally shallow but needed to be dug deeper to reach cooler temperatures. More work needs to be done to prove whether this hypothesis is accurate. The team will now excavate the western half of the pit, which will hopefully yield evidence that sheds more light on the pit’s function and date. Once this pit has been fully excavated, the team will move to the next one, eighteen feet to the east.

Just a foot or so north of the pit, a palisade wall runs in an east/west line dozens of yards in either direction. Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown is excavating a small section of the palisade, and has exposed the outlines of its wooden posts. He has excavated one of the postmolds to its bottom, just a few inches below the modern surface. The shallow nature of this feature proves that a large amount of soil has been lost from this area; palisades normally extend two to three feet below the historic ground surface. Right now, there are no diagnostic artifacts that can date this feature. Some items — such as a glass shard and a lead shot — have been found, but these are not easily dated. Bermuda limestone is embedded in the palisade in some places, which indicates the feature must date to post-1610 (the earliest arrival of people and objects from Bermuda) but this only tells us the time after which the palisade was created, not the exact year.

At the beginning of this month, the team hosted the second of our two Kids Camps. Twelve campers joined the archaeologists in excavating at the borrow pit site, where a 17th-century clay mine was located. The campers moved huge amounts of dirt, uncovering a variety of archaeological features. These included the borrow pit itself, as well as a 17th- or 18th-century zigzag ditch, and a test trench from archaeology in the 1940s. Besides excavation, the campers learned about ground-penetrating radar (GPR) from Director of Archaeology David Givens. Both this session’s campers and those from July used the GPR machine to great effect, finding the remains of a brick cellar just north of the Memorial Church. This previously-unknown building is an exciting find, and one the team may explore in the coming years.

Officially joining the team this month is Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis. A graduate of the Jamestown Rediscovery Field School, Ren has been excavating alongside Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch at the borrow pit. The team has built on the finds from the Kids Camps, uncovering several more features, including a second ditch and a mysterious ash-filled feature. Unfortunately, this site is next to the expanding Pitch and Tar Swamp, and has been repeatedly inundated. The difficulties with flooding highlight the increasingly dire effects of sea level rise and climate change on Jamestown Island. All of Jamestown Rediscovery is working to solve the ongoing damage from rising waters on the cultural resources that define the beginning of English America.

In the Rediscovery Center the campers got a behind-the-scenes look at what happens to artifacts once they come in from the field. In the lab, Archaeogical Conservator Don Warmke taught the kids about his specialty, the conservation of iron artifacts. The campers were able to see examples of artifacts before and after conservation — such as sword hilts and gun locks — up close. Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens shared glass and ceramic artifacts of both European and Virginia Indian origin and explained how they were used. Assistant Curator Emma Derry showed the kids a sample of animal bones found at Jamestown and explained how they can be used to infer things about the people who ate them and the environment they shared.

Several yards to the west of the Governor’s Well archaeologists are fighting a tangle of pine roots to uncover an early ditch. There is very little of it left due to the construction of Fort Pocahontas‘ moat in 1861 and the roots are making it difficult to reach what remains. Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas is overseeing the excavations here and artifacts found this month include an English pipe bowl and a projectile point the type of which was in use at the time of Jamestown’s settlement.

Contract zooarchaeologists Stephen Atkins and Susan Andrews have begun an analysis of the faunal material from the James Fort’s first well. Atkins and Andrews worked on the same process for the Fort’s second well; you can read about their findings in their report Jamestown Colony: From Food Dependence To Food Independence. The two began their work on layer “W,” one of the oldest (and hence deepest) layers of the well, likely deposited during the town cleanup ordered after the arrival of Lord De La Warr in June 1610. Like other wells at Jamestown, the first well served as a trash depository when its water ceased to be potable. And the trash — just in layer “W” — consists of over 90,000 bones, with the majority belonging to fish (including sturgeon and gar), small mammals, turtles, birds, and even venomous snakes. Squirrels are well represented in the assemblage, but very little in the way of large mammals. Among the bird bones identified by Atkins and Andrews are the first cormorant beak and the second heron beak in the Jamestown collection. This layer is thought to represent the diet of the colonists during the Starving Time winter of 1609-1610, when they were under siege by the peoples of the Powhatan Confederacy and venturing outside the fort’s walls to hunt larger animals could mean death at the hands of the besiegers. The zooarchaeologists noted that typically around 30% of animal bone in archaeological contexts is identifiable, but in this case that number is about 70%. This is due to the relatively good condition of the bones, perhaps an indication that they were dumped in the well shortly after being consumed rather than left out in the elements for decades or centuries as is typically the case in archaeological contexts. Atkins and Andrews spent about 6 days on this initial sort and identification. Many more layers and much more work lays ahead.

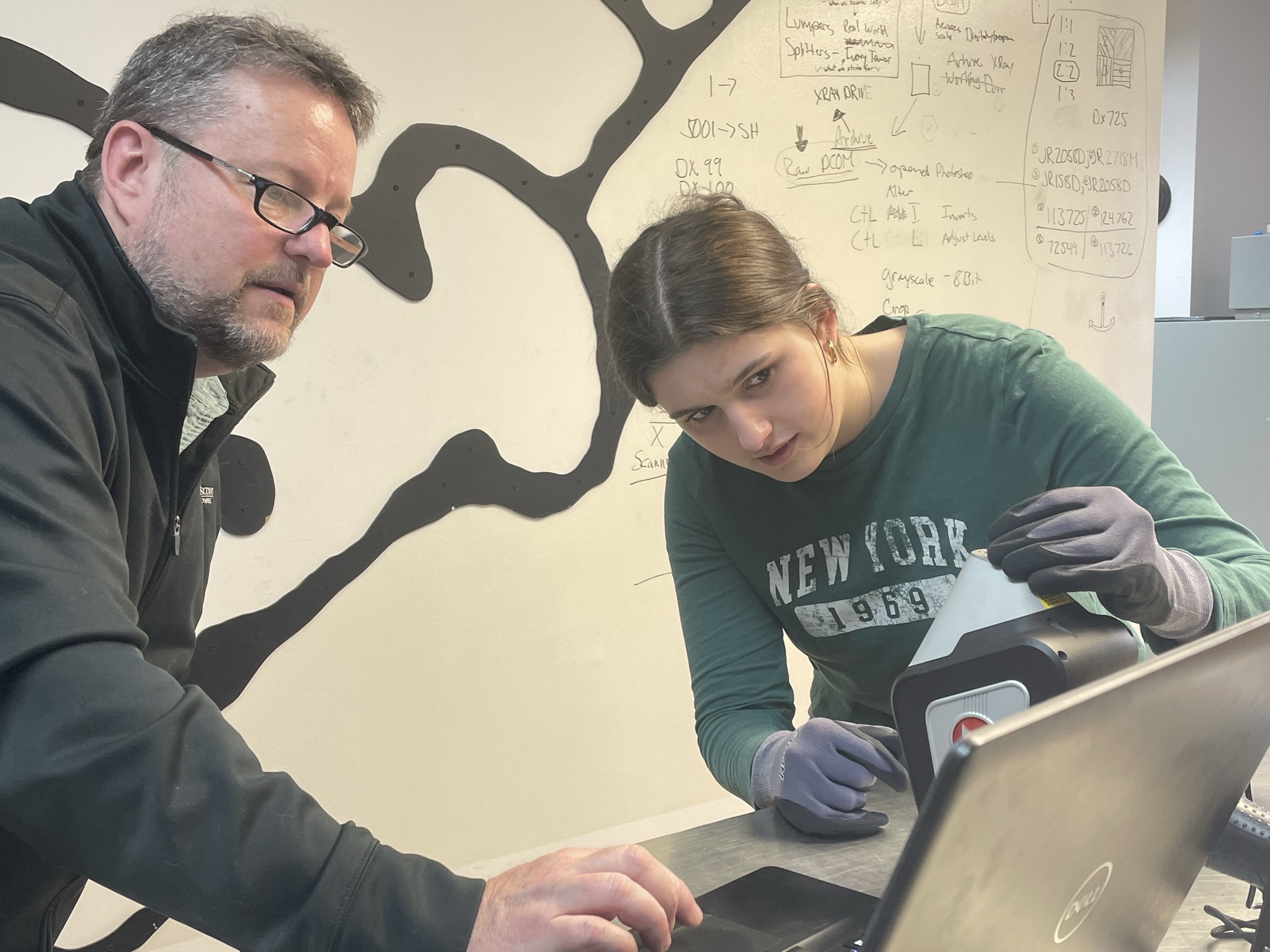

Collections Intern Ava Geisel has completed her internship with Jamestown Rediscovery where she was an invaluable resource to the project on a number of fronts, with a focus on the button collection. Her work to gather, organize, and analyze the button collection with Assistant Curator Janene Johnston was an important piece of the larger reference collection project, where the collections and conservation teams are finding, gathering, and conserving examples of each type of artifact for easier access and study for both inside and outside researchers. Those researchers interested in learning about all examples of a certain type of artifact can then access the archives to analyze further such examples. Ava’s internship included the use of X-ray and LIBS technologies to better understand the composition of the buttons for more effective conservation. We are grateful for Ava’s time and efforts. You can read more about her internship in her blog post “Working with ‘Old Stuff'”. Stay tuned for the second part of her blog, which will specifically highlight her work with the button project!

Christopher Egghart, an expert in Native American stone tools, visited Jamestown this month and lent his knowledge to our curatorial staff in their efforts to complete the lithic reference collection. Egghart identified 50 new projectile points, adding to 500 he had previously identified or confirmed. Though there are approximately 1200 projectile points in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection, many of them are too fragmentary to identify. Additionally, Chris reviewed some of our identified stone tools including axes, celts, drills, and nutting stones. Through this process, he identified an awl and discovered that one of our gorgets appears to be a reworked ulu. We hope to have Chris back again in the future to review the remaining materials which includes tools such as scrapers, hones, and blades. Jamestown’s collection of lithics originate from the Paleolithic era several thousand years ago up until the time of the settlement of Jamestown and indicate a millenia-long period of use of Jamestown Island by Virginia Indians.

In the lab, Archaeological Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins continues his work on some of the bone-handled knives in the collection. Using air abrasion, he is removing concretions of corrosion and dirt. As he carefully reveals their original surfaces, Chris has discovered that a small number of them (5 out of the approximately 300 in the collection) bear silver inlay decoration. He has also used the X-ray machine to great effect to determine how best to approach his conservation for each individual knife. In January, Chris’ lab mate Archaeological Conservator Don Warmke discovered a bone-handled knife with silver inlay that matched the design of one found at Martin’s Hundred, a settlement just downriver from Jamestown. Senior Archaeological Conservator Dan Gamble is conserving a bell fragment found during excavations of Jamestown’s brick church that was in use from approximately 1639 until the 1750s. This is the second such fragment he’s conserved in the past few weeks and similar to other efforts in the collections and conservation departments, his goal is to help populate artifacts in the reference collection. The bell fragments that Dan has been working on were also part of the project to make the bell reproductions — they were measured and used to develop an accurate size and design for the reproductions, one of which is currently hanging in the Memorial Church and is occasionally rung.

related images

- A wide-angle view of the well

- Members of the archaeological team discuss the Governor’s Well excavations. (L-R) Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley, Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown, Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reed, Director of Archaeology David Givens.

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis hoists up soil excavated by Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch. The soil will be screened for artifacts or put in sandbags for for flotation.

- Archaeological Intern Eleanor Robb digging in the well’s builder’s trench.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid holds a sherd of Virginia Indian pottery that she found while excavating the Governor’s Well.

- Archaeological Field Technician Gabriel Brown slowly scrapes away at the fill inside the Governor’s Well.

- The Governor’s Well. One quadrant of the builder’s trench has been excavated. All quadrants will be excavated to the same level before progressing further downwards.

- The crew films an episode of the YouTube series “Dig Deeper.”

- Archaeological Field Technicians Gabriel Brown and Hannah Barch prepare one of the squares at the clay borrow pit for a drone record shot. The yellowish scored rectangle is J.C. Harrington’s 1941 trench. Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford holds the drone remote, ready to take the shot.

- (L-R) Archaeological Field Technicians Gabriel Brown and Ren Willis, and Archaeological Interns Eleanor Robb and Janne Wagner screen for artifacts while Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber conducts excavations. This is at the clay borrow pit excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid discusses the Kitchen and Cellar excavations with the campers.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley discusses the significance of some of the artifacts of the Gentleman Soldiers exhibit in the Archaearium museum.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and the campers discuss the archaeology journals the kids used to record their activities and findings.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas oversees some campers screening for artifacts.

- Campers conducting excavations at the clay borrow pit.

- A camper troweling away at one of the squares in the clay borrow pit excavations.

- A camper holds a fragment of a pipe stem he found.

- What artifact? I don’t see an artifact!

- Campers carry a bucketful of excavated dirt to the screening area.

- Flooding at the clay borrow pit excavations. Inundation of the archaeological resources is becoming a more frequent problem and is detrimental to the historic features, artifacts, and human remains.

- Director of Archaeology David Givens instructs campers on conducting ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys.

- Director of Archaeology David Givens discusses the findings of the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey that the campers conducted.

- Archaeological Conservator Don Warmke shares a conserved rapier hilt with the Kids Camp attendees.

- Assistant Curator Emma Derry and campers discuss some of the animal remains found at Jamestown and what they can tell us about the people who lived there.

- The campers discuss their experiences at camp with their families on the last day.

- At the clay borrow pit excavations, archaeologist J.C. Harrington’s trench from 1941 is clearly visible.

- Excavations at the clay borrow pit

- Screening for artifacts at the clay borrow pit excavations. (L-R) Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber, Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas, Archaeological Intern Janne Wagner, and Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch.

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis shares some of her findings during water screening.

- Excavations at the ditch near the large pine tree. Things have been slow going here due to the roots.

- A pipe bowl fragment sticking out of the dirt at the west ditch excavations

- A projectile point found in the west ditch excavations. The point is of the right type to have been contemporaneous with Jamestown’s settlement.

- Director of Archaeology David Givens backfills excavations north of the Church Tower.

- Assistant Curator Janene Johnston holds a sample of the projectile point fragments in the Jamestown collection. The problem with many of the points is that they are too fragmentary to identify as their shape is so important to that task.

- A drawer of projectile points in the Vault. Many more can be seen in the Archaearium museum.

- A Virginia Indian slate gorget. The gorget is a modified ulu, a type of knife. Note the hole used to hang the gorget around one’s neck.

- A Virginia Indian projectile point

- Some of the bones from Jamestown’s first well after the initial sort was completed.

- A knife found at Jamestown, probably from the late 19th or early 20th century. The top photo shows how it looked after being excavated by our archaeological team. The center image is an X-ray taken by Dr. Chris Wilkins, Archaeological Conservator. X-rays help inform the conservators’ choices for treating the artifact. And the bottom photo shows the partially-conserved knife thanks to Chris’ efforts.