This April, Jamestown Rediscovery opened two new exhibits. The first marked the exact spot where democracy began in English North America with the first General Assembly in 1619. Within the 1907 Memorial Church, archaeologists have delineated the outline of the Quire [choir] and chancel of the timber-frame church. Visitors can stand on the very spot where representative government began and future programs will recreate this historic event.

For over 100 years, the Memorial Church has given the visitor an accurate visual representation of the 1640’s brick church it is built over. With the recent discoveries at the site and inside the tower ruin, a partial reconstruction of the earlier 1617 timber-frame church is under construction to represent the wooden building whose foundations are just inside the brick church. Using surviving English churches, furniture, and historic references, the renovation gives the viewer a sense of scale and a period correct appearance. A belfry is also being erected at the west end to incorporate the recreated Jamestown bell. Fragments from the bell were recovered throughout the archaeology project’s 25-year history and might represent one of the two bells referenced in the 1608 church. This bell and first person interpretations will recreate the historic event of the first General Assembly which occurred in this space in 1619.

Galleries in the Voorhees Archaearium Archaeology Museum were transformed with the introduction of the new “Fort to Port” exhibit, which explores how Jamestown evolved from a small triangular fort into a major port in the Atlantic Seaboard within 12 years. The exhibits explore difficult themes such as the genesis of an English system of African slavery, the ‘othering’ and exploitation of Africans and of Virginia Indians, and the establishment of a plantation society. Special artifacts, such as a cowrie shell from the NPS “Angela site,” are highlighted in wall cases that present these themes, while another case interprets the cellar of a wealthy landowner who burned his own home during Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Loaned by the Pamunkey Council, a replica of the Pamunkey frontlet given to chief and Queen Cockacoeske for the treaty made after the rebellion is displayed.

Jamestown’s final Statehouse, located directly under the site of the Archaearium Museum, burned during the Rebellion and again in 1698. Part of the new gallery interprets its artifacts in a case within a model of a brick wall that is superimposed just above the genuine Statehouse foundations visible in the floor portals on site. Another case relates to tobacco culture, and the “end of an Era” case highlights material culture from the end of the 1600s including a wine bottle of Francis Nicholson, the governor who moves the capitol from Jamestown to Middle Plantation (Williamsburg) after the Statehouse burned the final time.

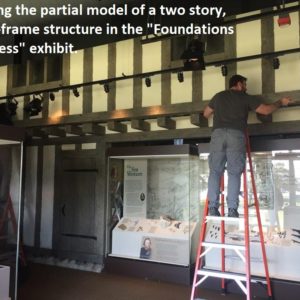

“A Foundation for Success” exhibit builds on decades of excavation in and around James Fort and details the architectural chronology from the first structures to substantial brick buildings. In the same part of the museum where a cutaway shows mud-and-stud construction, there is now a partial model of a two story, timber-frame row built—like the 1617 church—on cobblestone footings after the Starving Time of 1610.

The team also added a panel and new case devoted to zooarchaeology, the study of animal bones. It is divided into the wild animals eaten before the Starving Time, and domestic animals consumed after the settlement started to become more established. The post-Starving Time period of Martial law is also evident in the ceramics relating to foodways, whereby food preparation and consumption became more communal and structured.

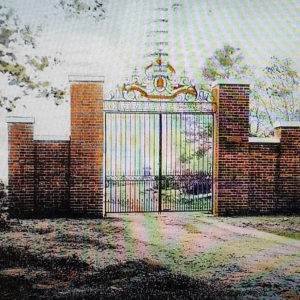

Besides the new exhibits in the Memorial Church and Museum, Rediscovery has focused on restoring the entrance gate to Preservation Property, which was given by The Colonial Dames of America around 1907. When it was first installed, the gate was located closer to the James River. Pictures of structure from the 1940s show a gate house constructed next to it and turnstile off one end. The gate was moved to its present location around the mid-1950s as Preservation Virginia and their partners, the National Park Service, prepared for a visit from Queen Elizabeth II during the 350th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in 1957.

Over the last century, the gilding on the symbols have faded, the steel has rusted and four of the arrows on the gates have disappeared. “It is a marker for all visitor traffic coming onto our property,” said Director of Conservation & Collections Michael Lavin. “It’s the first thing you see, and it had fallen into disrepair.”

With support from the Colonial Dames of America, Lavin supervised Jamestown’s restoration efforts, which he hopes will be completed this summer. This month, Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists began excavations around the gates hoping to find structures related to the expansion of James Fort after 1608. Before archaeologists place a shovel in the ground, they are conducting a ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey of the area to see what might be in store for them.

This month’s Jamestown Rediscovery YouTube channel video highlights the process of returning the Knight’s Tombstone to the Memorial Church. Archaeologists moved the stone’s location to the center of the newly discovered chancel for the 1617 Church. Although archaeologists have not uncovered positive evidence for where the tombstone originally sat, the previous place it occupied was also not its original location.

related images

- Outlining the footprint of the 1617 Church inside the Memorial Church

- Installation of the new floor in the Memorial Church

- Installation of the new floor in the Memorial Church

- Installation of the new floor in the Memorial Church

- Archaeologists built a ramp across the Tower archaeology in order to return the Knight’s Tombstone to the church

- The team lowers the Knight’s Tombstone

- Monuments Conservator Jonathan Appell scoops away excess water and ice from around the stone as it melts into place

- Michael Lavin, Dan Gamble, and Leah Stricker examine the Knight’s Tombstone after the ice has melted

- The installation of the new panel for the “Fort to Port” exhibit

- Jamie May and Michael Lavin during the installation of the new exhibits in the Archaearium

- Associate Curator Leah Stricker places artifacts in a case representing the Drummond cellar, which was burned during Bacon’s Rebellion. Although mostly empty when it burned, remnants of charred wooden barrels and buckets were found on the cellar floor.

- Senior Curator Merry Outlaw places window lead in the Francis Nicholson cellar case. The cellar contained many complete wine bottles, including one with Francis Nicholson’s wine bottle seal.

- JR Curators and Conservators work to install the new exhibit in the Archaearium.

- Installing the partial model of a two-story, timber-frame structure in the “Foundations of Success” exhibit

- The Memorial Church after the completion of the new floor with the Knight’s Tombstone in place. New hand-crafted pews mark the quire (choir) where the first General Assembly met in July 1619.

- The Knight’s Tombstone in the Memorial Church

- Old postcard of the Colonial Dames gate at its original location close to the James River

- The gate presented to Preservation Virginia by the Colonial Dames of America as it appeared prior to recent restoration efforts.

- Archaeologists Bob Chartrand and Les Jennings prepare for a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey next to the entrance gate.

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand conducts a GPR survey by the entrance gates prior to Rediscovery’s excavation.

- The restoration of the gate

- The restoration of the gate