Conservation and research of a marked sword blade from the Governor’s Well

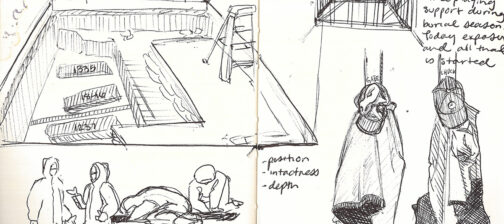

Archaeologists recovered many swords and sword elements while excavating the Governor’s Well in the fall of 2023. However, the very first one to come out of the ground has proven to be one of the most intriguing finds from the feature. Five elements found together in situ are likely part of the same sword blade. Unfortunately, the hilt, grip, and pommel are missing, making the date and place of manufacture difficult to determine. Bricks discarded in the well were cemented to the iron blade by corrosion as it lay in the moist ground for 400 years.

As soon as excavators brought the sword into the lab from the field, it was dry-brushed and cataloged. Based on its measurements, it is likely a broadsword.

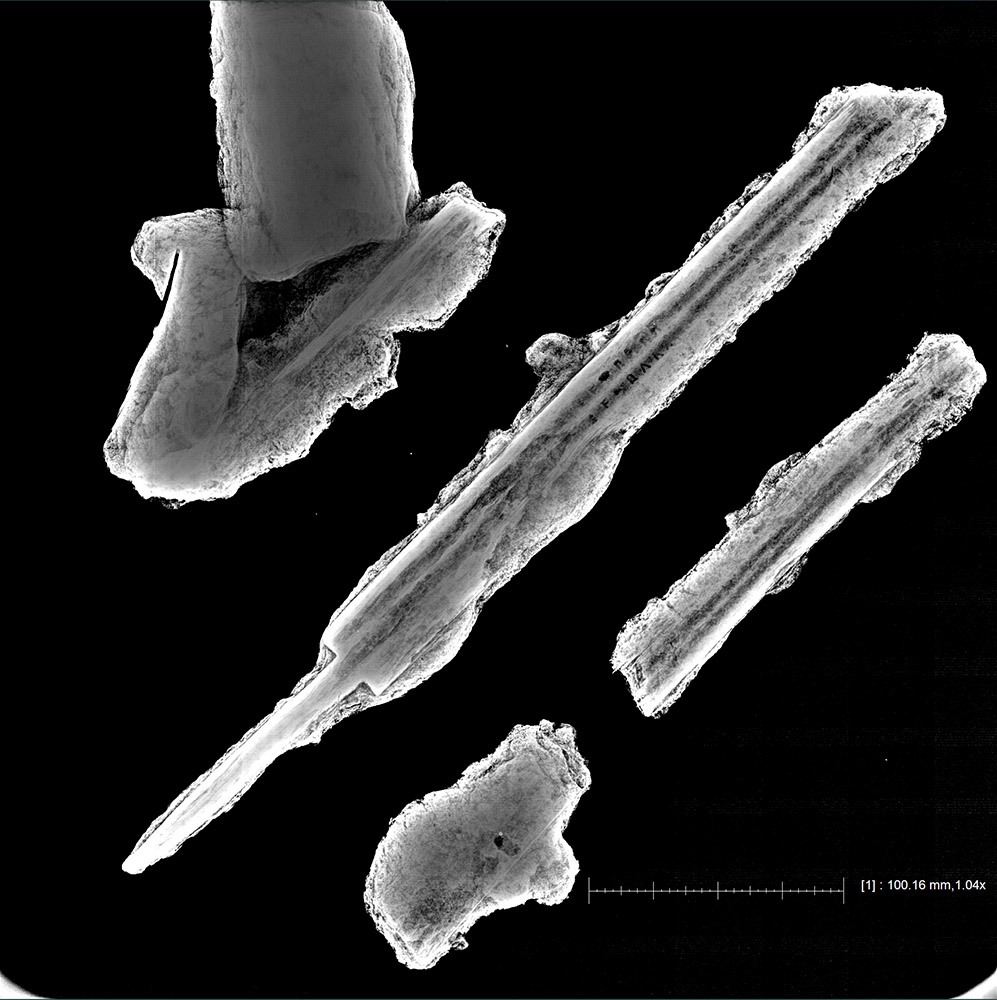

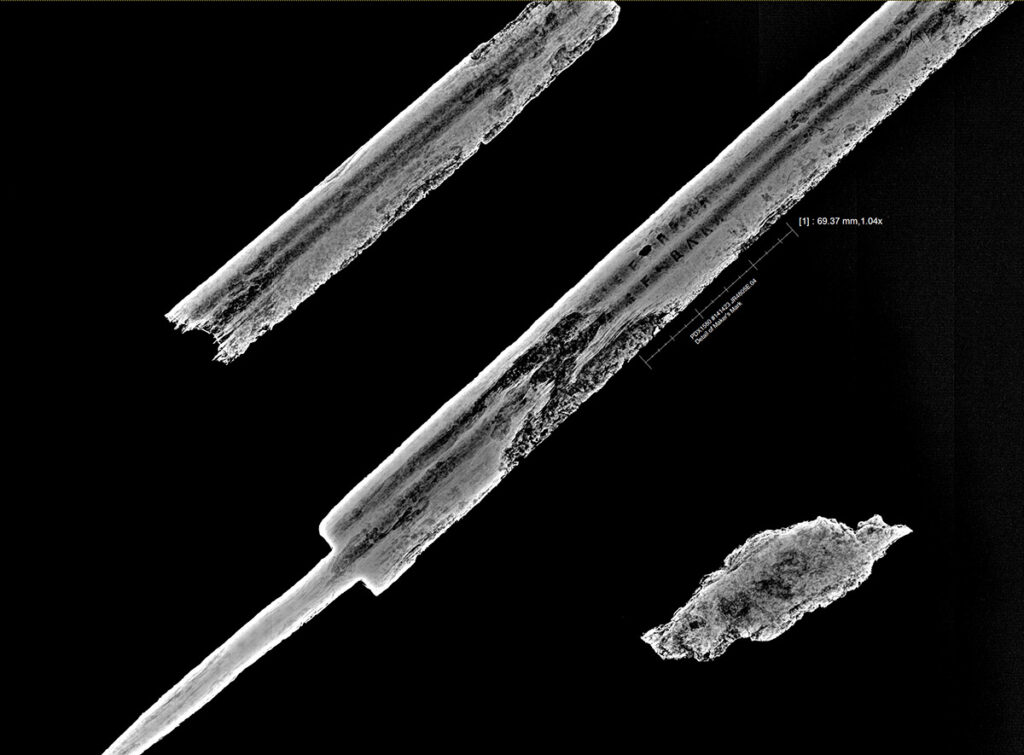

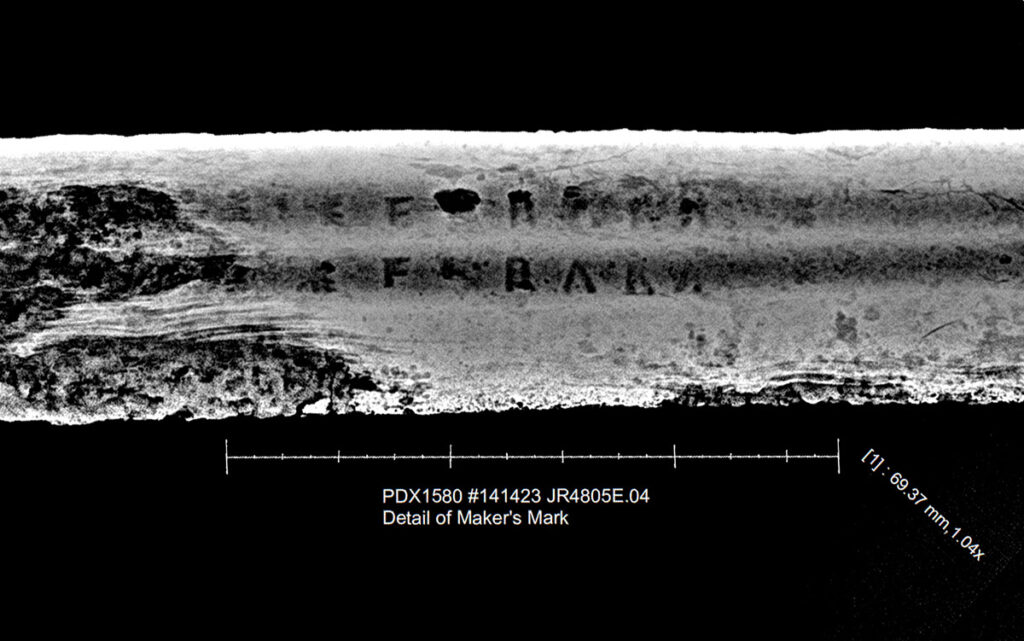

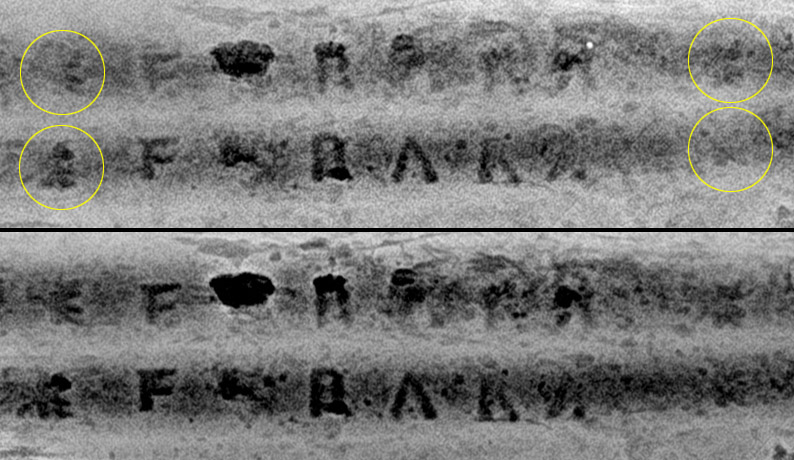

Conservators x-rayed the fragments, which revealed a maker’s mark on one side, which included letters, symbols, and possibly a number. Since this is the first marked sword blade from all of Rediscovery’s excavations, the reveal was exhilarating! The name “FERARA” appears one above the other within each of the blade’s fullers — along with an unknown symbol before the letter F and after the final A.

Next, the corrosion and concreted brick fragments were removed using air abrasion, and a second x-ray was taken to determine if the mark was easier to see. The marks before and after the name are somewhat more apparent but are still unidentified.

The blade was placed in a desalination bath (sodium hydroxide) for about 2 months to remove chloride salts that cause iron to corrode in lower relative humidity. In late March 2024, conservation of the two largest fragments of the blade were completed! Before conservation, the longest blade fragment was approximately 45cm long and 4cm wide and displayed minimal tapering from the tang to the broken end. Now that the conservation process is complete, we hope to see as many pieces of the blade as possible together to better understand the overall length. The conservation treatment that the sword has undergone will stabilize the artifact and preserve the mark. The sword is now housed in long-term storage, where it will be monitored for corrosion outbreaks. Perhaps one day it will go on display in the Archaearium museum.

The name Andrea Ferrara is one of the most ubiquitous marks found on 17th century swords. The widespread use of the name and variations in spellings, symbols, and other stylistic differences of the mark suggest that multiple individuals and workshops produced them. While a maker’s mark is generally intended to connect a product immediately to its maker, which can not only date the artifact but also provide a place of manufacture, the sword from the Governors Well is much more mysterious.

At some point, perhaps in the 17th century or even earlier, the mark of Andrea Ferrara began to be associated with a high quality weapon. This in turn led many English and European swordsmiths to use the name fraudulently on their products to enhance the perceived craftsmanship and value of their work. This explains the ubiquity of the mark. So who is this Andrea Ferrara?

The identity of Andrea Ferrara has been an enigma for centuries. A number of 19th century antiquarians attempted to track down an individual with the name Andrea Ferrara, noticing the mark in historical documents and on extant swords. Sir Walter Scott, renowned Scottish author and arms collector writing in several historical accounts, diaries, and correspondence throughout his life, noted that Andrea Ferrara’s name was inscribed “on all the Scottish broadswords that are accounted of peculiar excellence.” (Scott, 1814)

The association between Ferrara and good quality Scottish basket-hilted broadswords became so strong that the swords themselves started being referred to as “Andrea Ferraras,” as in, “when he is armed with his pistols and a Ferrara, has good effect.” (Gilpin, 1792 p. 230). This association extended to literary works by prominent figures like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (of Sherlock Holmes fame, writing c. 1889) and J.M. Barrie (of Peter Pan fame, writing c. 1890), who used the name to describe swords in their writings.

However, this early research was founded upon dubious facts, and Andrea Ferrara remained a mythological figure. According to early investigations, Ferrara was either Spanish or Italian. He supposedly not only exported swords from his home country but also traveled to Scotland to teach local metalsmiths his techniques. Depending on the account, Ferrara was invited to Scotland by King James III (reign: 1460-1488) (Gilpin, 1792), James IV (reign: 1488-1513), or James V (reign: 1513-1542) (Scott, 1814). In one account, Ferrara created a manufacturing operation in Scotland but was forced to flee the country after killing an apprentice who spied on his secretive sword making methods.

It was not until the 1980s that arms researchers confirmed that a real Italian swordsmith named Andrea Ferrara existed and had a connection to the English market. Andrea Ferrara and his brother lived and worked in Belunno, near Venice, Italy. He was born sometime in the 1530s and died in about 1612 (Blair, 1998). On December 5th, 1578, the Ferrara brothers agreed to supply 600 swords to two English merchants monthly over ten years. Whether the massive order included marked swords or if the brothers made all 72,000 swords for the English market is unknown. If Ferrara made, marked, and fulfilled the late 16th century Englishmen’s order of at least some swords, it is conceivable that the sword found in the Governor’s Well was forged by him, purchased on the English market and brought to Virginia by an early settler who ultimately discarded their weapon at Jamestown. We may never know for sure. Although unique to Jamestown, this is not the only Ferrara-marked sword found in Virginia. Another one was found during excavations in Hampton, Virginia, at the site of Fort Charles, which was established by Lord De La Warr in 1610. Perhaps the two swords were owned by men who knew each other 400 years ago in Tidewater, Virginia.

sources

Blair, Claude. “New Light on Andrea Ferrara.” The Arms and Armor Society Newsletter, May, 1984.

Blair, Claude. The Crown Jewels. Vol II. 1998.

Ferrara, Andrea. Sword (Rapier) and Scabbard. c. 1575-1583, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

Gilpin, William. Observations, Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty, Made in the Year 1776, on Several Parts of Great Britain: Particularly the High-lands of Scotland …. United Kingdom. London, R. Blamire, 1792.

Mowbray, Stuart. British Military Swords. Volume 1: 1600-1660. The English Civil Wars and the Birth of the British Standing Army. A. Mowbray, 2013.

Pickup, David R. “Simon Mayne, Regicide, and Dinton Hall.” Records of Bucks. Volume 54. 2014.

Royal Armouries. “Weapons in Society conference – Day 2 – Keynote – Would the real Andrea Ferrara please stand up?” YouTube, June 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67-VE9DUo9U.

Scott, Walter. Introductions, and Notes and Illustrations to the Novels, Tales, and Romances of the Author of Waverley. Volume 1. Edinburgh, R. Cadell, 1833.

Staples, Hamilton B. “Presentation of the Sword of Fitz-John Winthrop.” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, October 1887.