February has been a busy month for the Jamestown Rediscovery team. While the archaeologists continue their work on the artifacts found at the Angela site, an unusually warm day allowed them to do some ground-penetrating radar (GPR) work in the Pitch and Tar Swamp. In the Jamestown Rediscovery Center, the curatorial team is excited to hand off a collection of bones found in the fort’s second well to a team of zooarchaeologist consultants who are experts in faunal remains. Our curators are hoping the analysis will identify the species of the animals, their quantity, and if possible determine what the colonists used them for. In the conservation lab, analysis is being done on a wooden bowl found in the same well. The bowl is unusual in that wooden artifacts rarely survive on archaeological sites. However, wooden bowls and plates were likely more commonly used than ceramic or pewter tablewares. Wood was cheaper and thus more accessible to the common Jamestown colonist, while ceramic and pewter vessels were likely only owned by wealthy gentlemen. Flotation samples from three fort-period features have been received after processing and analysis by an archaeobotanist. Some interesting artifacts have been found during the process. Archaeologist and photographer Chuck Durfor is working on a virtual tour of the Archaearium that will allow folks to “visit” our museum via our website and learn more about the artifacts on display there.

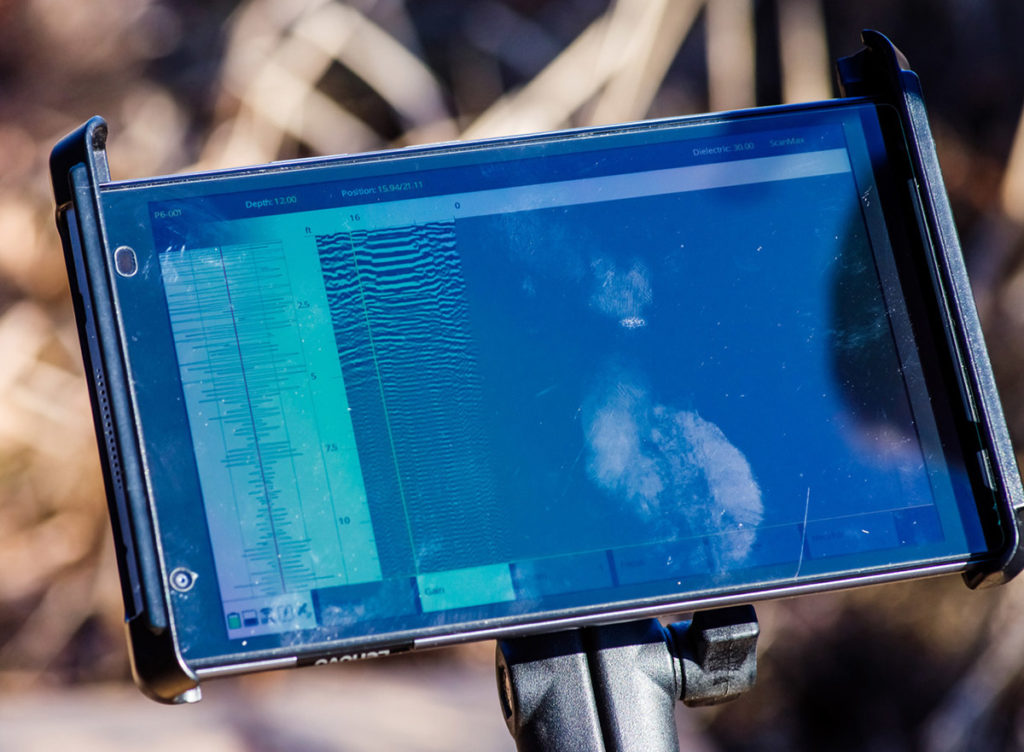

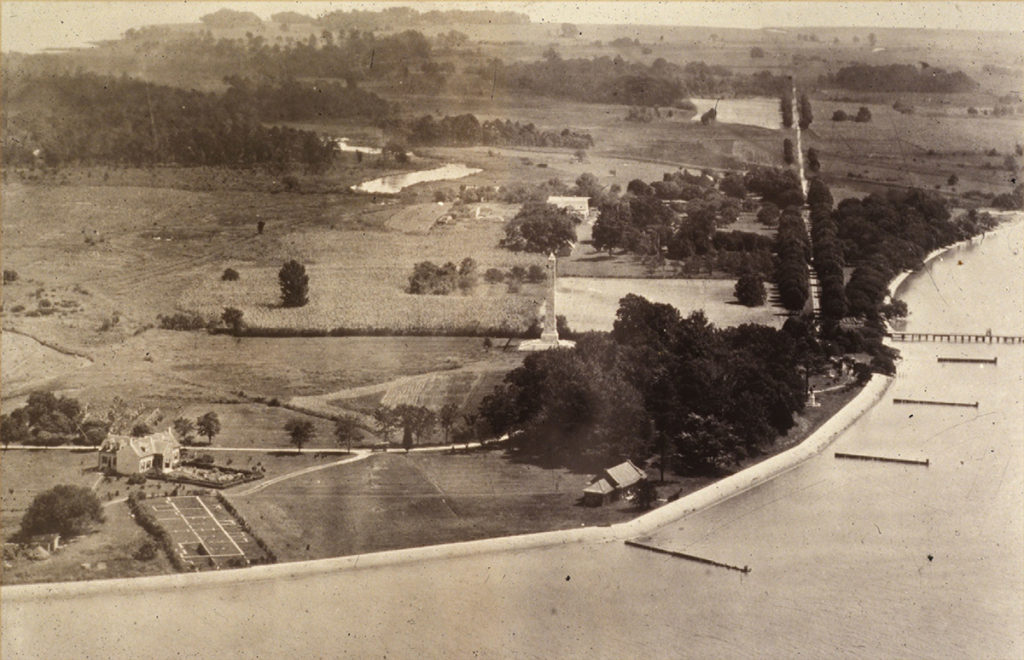

When a seventy-degree day presented itself, several of the archaeologists took a break from their lab work to explore a branch of the Pitch and Tar Swamp, created in the past 150 years due to sea level change, by using ground-penetrating radar (GPR). The wetland has swallowed more low-lying land over the years, growing rapidly in the past few decades. In the 1930s and 1940s the area was solid ground, allowing archaeologists to conduct excavations in the area. Among the findings at that time was evidence of a clay pit that may have been used as a source for clay for brickmakers in the 17th century. Back to the present day, the team conducted a proof-of-concept test to see how well GPR would work in the swamp environment. Plywood boards were used to create a solid, dry pathway for the GPR device and minimize the impact on the swamp itself. The device uses a 350 MHz antenna, a relatively low frequency that is used to penetrate further into the ground and see features at depths unreachable at higher frequencies. Obversely, GPR devices using a higher-frequency antenna will obtain more detail at the expense of a shallower reach. The team was able to record data to around 12 feet below the surface and the data is currently being analyzed by Director of Archaeology David Givens.

Contributions to the Merry Outlaw Curatorial Conservation Fund have allowed our curatorial team to submit over fourteen thousand bones found in the fort’s second well to faunal experts for further identification and analysis. Our collections team completed initial sorting of the bones by sorting them into broad classifications such as mammals, birds, and amphibians. But additional analysis by expert zooarchaeologists will be used to expand our knowledge of what animals the colonists were using in the years between the well’s construction in 1611 and later in that same decade when it was filled in. We’re hoping to learn a number of things through this further analysis including a complete list of species present in the second well, the quantity of each species, the age of the animals at the time of their death, and the identification of butchery marks that would indicate the animals were used as a food source. The first half of the project was completed in September 2021 and its report includes a narrative based on historical sources detailing how the colonists procured food in the early years of the colony. The second half of the analysis is due to be complete in December 2022..

A small wooden bowl found in the same well is undergoing analysis by our conservation team. Because the bowl was submerged in the anaerobic environment of the well for so long it was well preserved when it was found in 2006. After its discovery, the bowl was conserved through a process of polyethylene glycol immersion and vacuum freeze drying by conservators at Colonial Williamsburg. Archaeological Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins has mended the bowl where possible by using Paraloid B-72 as a glue. The process is reversible and will cause no damage to the artifact. Some of the pieces are too warped to join together. In addition to the fact that it’s a surviving wooden artifact, it’s also notable in that it was likely used by a colonist of average or lower means rather than a gentleman or gentlewoman. The surviving crockery found during our excavations is slanted towards the well-to-do as ceramics and metal objects survive (albeit often corroded in the case of the metal examples) whereas wood typically does not. So this is a rare object in the collection both in terms of form and association.

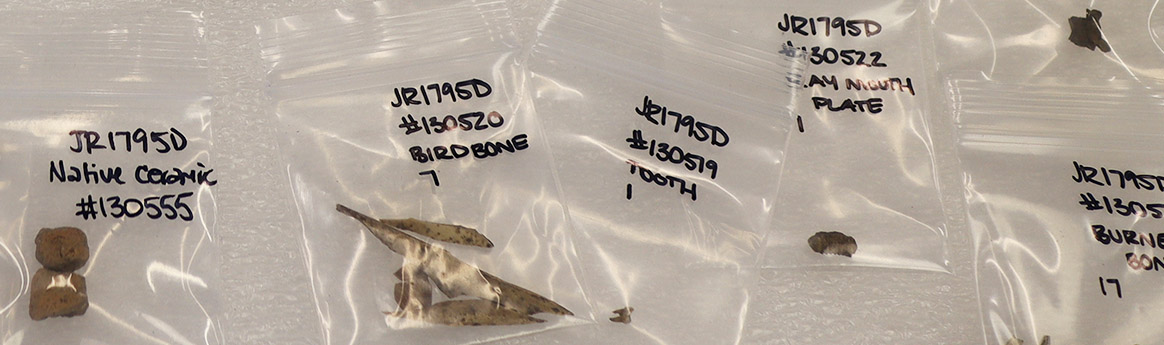

During the course of archaeological excavations samples of soil are occasionally set aside for flotation. This process uses water and mild agitation to separate out objects of different densities contained within a soil sample. Less dense objects, like burned seeds or small animal bones float and denser objects sink and meet mesh screens to further separate the objects by size. Samples for flotation are taken when archaeologists feel there is potential for botanical material to be found, such as areas where food was being prepared or trash middens, where food waste was being discarded. Tiny items and burned botanical material tends to float during this process, making it easier to gather and examine rather than possibly being lost in a traditional 1/4″ screening process. Samples destined for flotation are not subject to any prior processing to avoid such losses. The curatorial staff has recently been cataloging floated and analyzed samples from three fort-period contexts: the east bulwark, pit 8, and the first well. Some of the artifacts found after flotation of the pit 8 samples can be seen below. Pit 8 is thought to be a site of pipe manufacturing as an unusually heavy volume of broken pipe pieces and associated artifacts were found there.

Archaeologist and photographer Chuck Durfor is working on a virtual tour of the Archaearium museum funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Chuck has been the staff photographer for the Jamestown Rediscovery project for many years and has brought his skills and experience in that field along with his intimate knowledge of the artifacts in the Archaearium together in an effort to bring the museum to a wider, virtual audience. The project will also allow a much deeper dive into the artifacts than the exhibits there than can present in the physical space allotted to each artifact. Chuck is “stitching together” photographs of each exhibit with software that will allow visitors to look in every direction using their computer or mobile device. The limitless aspect of the web will allow any number of additional resources to be available to those who, for example, wish to see a video of the artifact being excavated or see contemporary parallels in other museums both here and overseas.

related images

The archaeology team brings a board over the top to extend the path for the GPR device.

Reading the GPR screen

Jamestown Island, 1930s

Jamestown Island, 2016. Border shows growth of Pitch and Tar Swamp.

An assortment of artifacts found in the pit 8 flotation sample

Curator Leah Stricker holds several fish vertebrae found in the flotation sample from pit 8.

The wooden bowl and unmended pieces